How this glucose monitor helps diabetics live longer lives and manage their condition properly, without the need to draw blood

- The new monitor allows diabetics to check their glucose levels, find patterns and anticipate changes

- It is vital for diabetics to keep their blood sugar within a certain range to avoid serious long- and short-term complications

For years, Sandy Shum, who has been a type 1 diabetic since the age of 17, was convinced she would die early, in her 40s or 50s. “I didn’t think I would live long – nor did I care,” the 30-year-old recalls.

She rebelled against her disease early on. When she was at university, she hid her condition, leading a lifestyle and following a diet similar to her fellow students. She seldom checked her blood sugar levels with the finger-pricking device as advised. If she ate a dessert with friends, she might inject a random dose of insulin in the hope of keeping her blood sugar levels down. The lack of precision in her dosage meant she regularly experienced sugar levels that were too low or too high.

Five sub-types of diabetes not two: study shows genetic differences

In Hong Kong one in 10 people have diabetes mellitus. Type 1 diabetics produce little or no insulin, a hormone that helps glucose enter the body’s cells. Type 1 diabetics require regular insulin injections.

In those with the more common Type 2 diabetes, the body does not make or use insulin well. When insulin levels are too low, the glucose isn’t taken up by the body and stays in your blood. Over time, this can damage the eyes, kidneys and nerves. Diabetes can also cause heart disease, stroke and even lead to amputation.

When blood sugar levels are high [hyperglycaemia], symptoms include frequent urination, dehydration, increased thirst and blurred vision. Long-term complications include poor blood flow, especially to the extremities, that can lead to damage to the retina, neuropathy [nerve damage], gangrene and amputation.

Very high levels of glucose [from missing too many injections, high stress or illnesses such as pneumonia] can cause a potentially fatal condition called diabetic ketoacidosis, where despite the amount of sugar in the blood, the body thinks it is starving and starts to break down fat. This process leads to a build-up of acids called ketones in the bloodstream.

The body removes water from cells in an attempt to flush out the glucose, causing dangerous dehydration levels and essentially concentrating the acid in the blood. This also removes essential minerals such as potassium, which is vital for the nervous system and the heart.

Simple blood test may reveal body’s inner clock and help cure ills

The condition also causes nausea and vomiting, removing even more water from the body. The lethal downward spiral can only be stopped with large intravenous doses of insulin, electrolytes and saline, and only if the person gets to hospital in time.

A low glucose level is known as hypoglycaemia. It is caused by injecting insulin and not eating enough. Symptoms include sweating, shakiness and fatigue, anxiety, hunger and confusion. Complications include seizures and loss of consciousness.

Diabetics are urged to monitor their own blood glucose levels, usually using a portable system that measures glucose concentration in a small drop of blood obtained through a finger prick and applied to a test strip.

Diabetics usually record their glucose levels in a logbook, so doctors can monitor their condition and recommend strategies to better control it. Shum often made up the numbers rather than using the device to actually measure them. “I spoke to other patients [like me] at the hospital, they said I’m not the only one who has done this,” she remarks.

Two years ago, Shum had a seizure after a bout of drinking. She randomly injected a dose of insulin, but it was not enough. She was rushed to hospital before dawn, alarming her husband. After this wake-up call, she started using the finger prick method to monitor her glucose about six times daily, but found the process exhausting. When she suffered a hypoglycaemic episode, for example, she had a blood draw every 10 minutes.

“If your glucose doesn’t rise you have to keep doing it and in the end, my finger … was full of holes,” she said.

I’ve learned that with exercise my [glucose] level goes up then it goes down whereas before I thought whenever I did exercise I thought my glucose level just went down

Last year she suffered another crisis that landed her in hospital. A serious of fevers and colds sent Shum’s health into a tailspin. After her glucose level was brought back under control, her husband went online to learn what he could do to ensure his wife’s longevity. Commenters in a US health forum recommended the FreeStyle Libre flash glucose monitoring system – no finger pricking required. He ordered it immediately and Shum became one of 800,000 diabetics in 44 countries using the device.

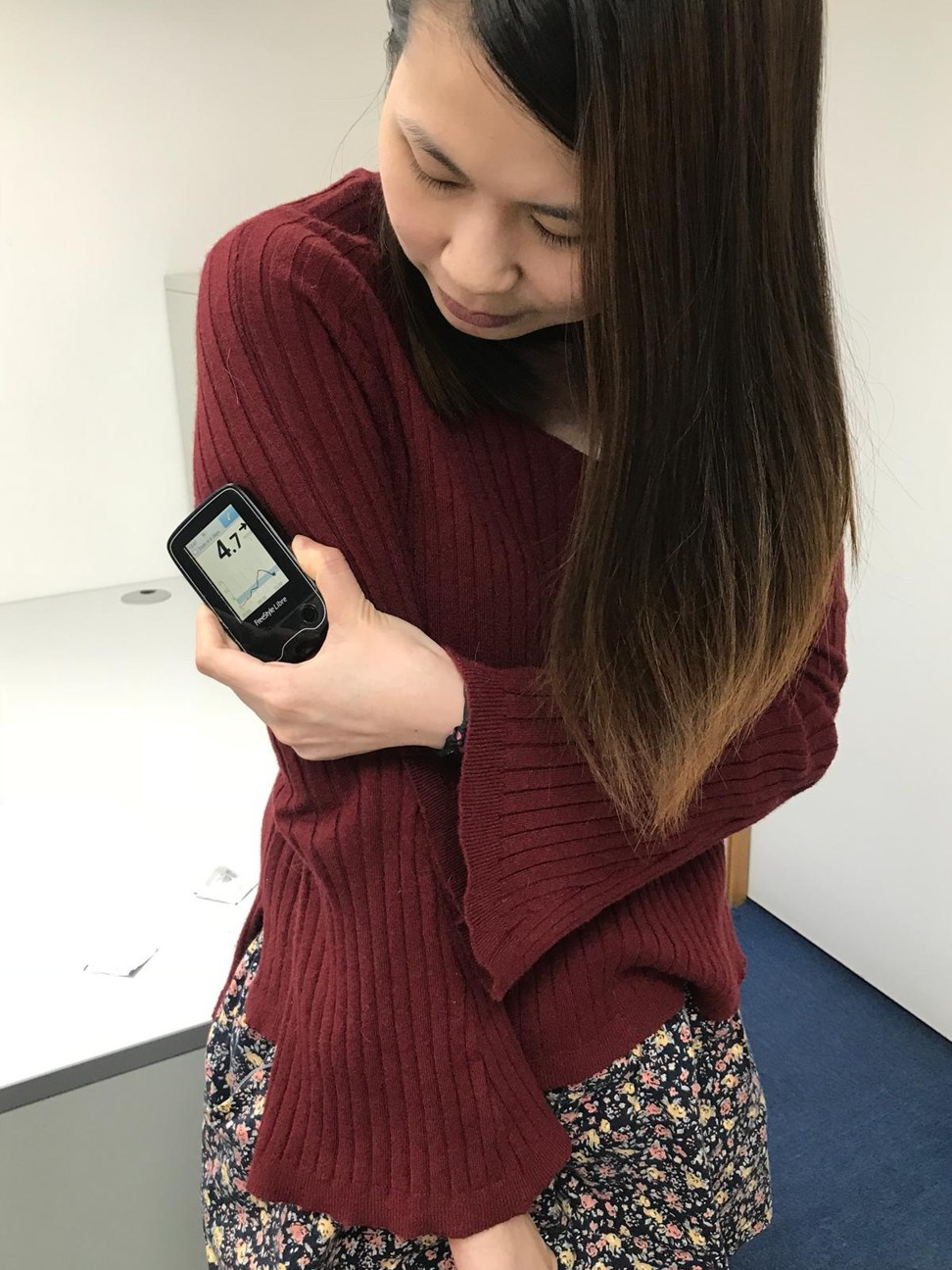

In Hong Kong, the product is for diabetics aged four and above. The user waves the small palm-sized “reader” over a thin sensor on the back of the arm for a reading from a thin, flexible fibre inserted under the skin.

The sensor checks the user’s glucose every minute and gathers the data into a report that compares the user’s glucose-level range over the course of the day versus the targeted range. The data is easily uploaded to a computer.

47pc in China have diabetes or are likely to suffer from it, study finds

Before adopting this gadget, Shum had a nihilistic ethos. “I’m going to die anyway so why don’t I enjoy my life?” she thought. After she saw her husband’s reaction to her hospital episode, her attitude changed: “I thought I need to take my disease seriously to figure out how I can live longer for him and control [my disease] better to have a baby with him one day,” she says.

Using this device prevents her from ‘faking’ her data, and her husband keeps a close eye on her levels by checking the reader.

The system is also able to recognise patterns in level changes, so she can act in advance. She learned that her glucose reading tends to shoot up from 2pm to 6pm on weekdays.

“Doctors told me how stress affects your blood glucose but none could specifically explain how big that impact was,” she says. The new data suggests her job affects her blood sugar levels, and that on weekends she requires a third less insulin than on weekdays.

Breastfeeding for six months or more almost halves diabetes risk

What was the connection? Her boss in Germany wakes up and calls her between 2pm and 6pm – which coincides with higher stress levels and glucose levels. “Now I can live with it: at 2pm I inject insulin in advance, I know that if I don’t, my blood glucose will rise,” Shum says.

She now leads a more normal life. Since she stabilised in the past year, her doctor has given her the green light to try for a baby. That prospect was too dangerous to consider before. “Now I can make my own choice,” she says.

For Zoe Lister, a 14-year-old with Type 1 diabetes, and an adopter of this device for two years, this technology shed much insight on sport’s impact on her body. “I’ve learned that with exercise my [glucose] level goes up then it goes down whereas before I thought whenever I did exercise I thought my glucose level just went down,” she says.

Netball and basketball in particular made her glucose drop quickly, so she has more food, particularly carbohydrates, before her games or brings extra snacks to eat during breaks.

She relishes the fact she doesn’t have to endure numb fingers any more from the traditional finger-pricking method, or the hassles of carrying around a bulky device with multiple components, including needles and swabs. She has misplaced various bits while setting up the system while travelling in planes or on lunch breaks at school.

In the cafeteria during meals, she no longer worries about entangling her machine components with friends’ stuff at the table. “I don’t have to go to the side where everyone would look at me.” She continues: “It’s so easy to do it now that nobody notices it, so I fit in more.”

The ease of this system means both women check their glucose more frequently, as often as 15 times a day, without blood, sweat or tears.