Building houses with 3D printing technology

3D-printed buildings could be the shape of things to come. In fact, it's happening already

Imagine if you could press "start" on a printer and watch your house take shape before your eyes. Well, it's happening already. From Shanghai to Amsterdam, from Los Angeles to London, the race is on to build the world's first commercially viable 3D-printed house. British architects Foster + Partners is going even further - it is printing a house for the moon.

We are told the technique has the potential to produce medical miracles and create just about any consumer goods imaginable. In construction, it's seen as a fast and inexpensive solution for providing shelter in areas of extreme poverty, or where disasters have occurred.

Architects also believe 3D printing is the key to the grand designs of the future, producing one-off, custom homes at a fraction of the cost of conventional building techniques. Potentially, it could make use of the mountains of rubbish we throw away as building materials.

In 3D printing, thousands of thin layers of material are printed on top of each other to form an object. The "inks" are most commonly plastic polymers and metals. The technology has existed since the 1980s although, until now, it has not been capable or cost-effective enough for commercial manufacturing.

"Expectations are high that these shortcomings are about to change," says professional services firm PwC, noting that of 100 industrial manufacturers surveyed, two-thirds were already using 3D printing.

Foster + Partners started its journey in January 2013, joining a European Space Agency consortium set up to explore the idea of a 3D-printed structure for human habitation on the moon, using lunar soil - known as regolith - as the building matter.

The lunar base can house four people, offering protection from meteorites, gamma radiation and high temperature fluctuations.

In its design, an inflatable dome provides a support structure for construction, upon which layers of regolith are built up by a robot-operated 3D printer to create a protective shell. Norman Foster calls the project - made in an earthly lab using simulated lunar soil - "a significant and pioneering step in space age construction".

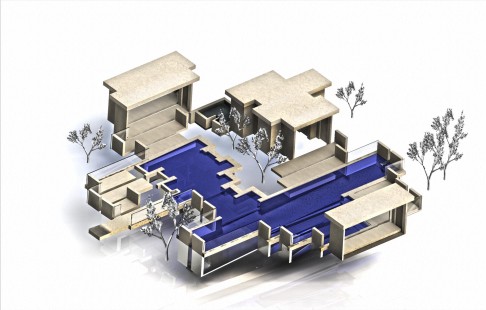

In the US, architect Adam Kushner, founder of New York's Kushner studios, is developing what he believes will be the world's first 3D-printed estate, complete with a 2,400 sq ft main house, pool and pool house. The Gardiner property will be his family's country home, he says.

While awaiting delivery of the six-metre-high printer in 2015, Kushner continues work on the design, and has engaged local contractors to begin foundation work for the pool.

"It is my plan to get the pool started in the spring of 2015, and have it mostly cast and completed by the end of the summer. I then hope to move on to the pool house by the autumn," he says.

Kushner views his project as an earnest attempt to make something beneficial that meets a diverse range of needs. "This is not about building a pool, or a second home. It's about working on a process which will change the paradigm of how we make, what an architect is, what a contractor is. 3D printing has the power to provide cheap emergency shelter, cheap and creative housing.

"My project happens to be a pool and a house, because that is the order that we need to experiment and work on the process, as well as meeting a need," he says.

Elsewhere in the US, Behrokh Khoshnevis, director of the Centre for Rapid Automated Fabrication Technologies at the University of Southern California, has invented an enormous 3D printer.

Khoshnevis says that it can make a 2,500 sq ft custom home in 20 hours. Contour Crafting, a patented system of computer-controlled robotic technology, lays concrete and interlocking steel bars to frame the structure for a multi-storey home, without need for human intervention.

"We're now developing the technology to ensure that not just walls are printed, but infrastructure like water and sewerage pipes as well," he says.

Khoshnevis estimates the potential cost savings to be around 60 per cent, including plumbing, wiring and tiling, with nearly zero waste generated during the construction. He hopes to see entry-level construction models on the market within two years.

In China, where urbanisation generates an estimated 1.5 billion tonnes of construction waste annually, a printer supplied by WinSun Decoration Design Engineering is credited with building 10 single-storey houses in 24 hours, using mine tailings at a cost of less than US$5,000 each.

The company, Shanghai Yingchuang Construction & Decoration, is now working on its next project, a fully designed 1,100 square metre house, and hopes the technology can one day be used to build skyscrapers. Both companies say that reusing waste in this way could have a significant impact on China's carbon emissions.

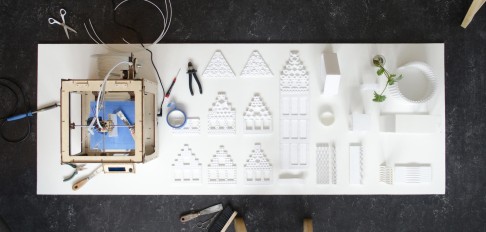

Speed is not of the essence for Dutch firm DUS Architects, which has allocated three years for the construction of its 3D-printed Canal House, as a "live" research project. The first stage of the pilot project opened to the public in February.

Hedwig Heinsman of DUS says the hope is that, over time, the house will develop into a mature 3D-printed building "with different rooms and material properties that all tell something about the time that they were printed". Already, she says, the second room printed is of higher quality than the first.

Designing for 3D printing gets more into a building's DNA than conventional architecture has allowed, Heinsman says.

"For instance, [on the Canal House] we designed an angled facade for [printed] solar panels. If we printed that same house in Hong Kong, we would input the geolocation, and the script would automatically adapt the design to the perfect angle for the sun conditions there."

The design time is faster. "We make a model with the small printer - if we think it's good, we can instantly print on the main printer so the whole process is much more direct."

Another advantage is the ability to create unique shapes - "richly ornamented bespoke shapes that are unique and tailor made," says Heinsman.

"If you want a conventional, boring house you can get a mass-produced house. If you want something unique and bespoke, you can get something 3D-printed, and probably at a fraction of the cost of what it costs now to make a unique house," she says.

For the Canal House, DUS has used bioplastic, a new plant-based building material made of linseed oil mixed with adhesives. Potentially, any material can be liquefied to use as printer "ink", including porcelain, clay, sand or whatever is readily available at the particular location.

"In the future you could also print with recycled plastic," Heinsman says.

"We could sweep out all the plastic in the oceans and start building with that."

DUS has also test printed with woodchips, creating a type of medium density fibreboard that enables unique shapes to be created from wood.

If you want something unique, you can get something 3D-printed

3D-printed buildings will eventually be a viable commercial alternative to current construction techniques. "It's not a matter of if, but more a matter of when," Heinsman says.

She also sees the technique expanding to "mass customisation", whereby, for example, you can pick the design of a chair, then personalise the seat height.

The fact that large partners are teaming up with DUS to be involved in the Canal House project shows that the wider industry believes so too, she says.

Houses built in hours rather than months, while at the same time sweeping the oceans clean. Buildings printed on the moon - what could possibly be next?

"I have a fantasy of a flying house - one that could float at a site until you've had enough, then move onto somewhere else," says Heinsman.