Buddhist mountain temple in South Korea on Unesco World Heritage List is a pocket of tranquillity in a rapidly modernising land

Daeheungsa is one of seven South Korean temples that have recently been inscribed on Unesco’s World Heritage List. Matthew Crawford takes a trip to the country’s far south to explore this startlingly beautiful location

The air around me ripples with heat as I peer down at a brown wooden rectangle planted in the gravel of a massive, open-air courtyard bounded by a low stone wall. “The spectator / rolls up / does not come in,” it reads. I stand there for a while musing upon this Zen riddle, before realising that it means “no entry” to the monks’ quarters beyond.

I have travelled south from Seoul, soon after the birth of my first child, to tour one of the seven sansa – Buddhist mountain temples – that have recently been inscribed on Unesco’s World Heritage List. I’m hoping to soak up some serenity, and perhaps even find a spiritual signpost or two to point me forward along the path of fatherhood.

We hike South Korea’s 71km Ultra Baugil trail in Gangneung

It is my last escape before the full duties of parenting set in, taken while my wife and child spend a short period of time in a sanhu joriwon, a South Korean facility designed to ease the transition to motherhood.

All seven temples are alluring: Tongdosa is said to contain relics of the Buddha himself; Bongjeongsa has one of the oldest wooden structures in the country; Buseoksa was founded by the pioneering monk Uisang; Beopjusa has a towering wooden pagoda; Magoksa harmonises stunningly with its natural surroundings; Seonamsa is the site of a famous stone bridge.

However, I’ve decided on Daeheungsa, possibly the oldest of the lot – one written source gives the founding date as AD426. It is also only 30km (18.6 miles) or so from Ttangkkeut, or “Land’s End”, the southernmost point of the Korean peninsula.

Though mentioned in few guide books, the Land’s End region, in Haenam county, is startlingly beautiful. Slopes of tangled green forest fall straight to the edges of even greener rice fields, with the occasional stand of bamboo tickling the sky. Where the land runs out, baring its rocky bones as it crumbles into sun-bleached sand, the scattering of hills turns into a scattering of islands.

The region has a long history of Buddhism. About 100km up the coast from here an Indian monk named Mirananta arrived in AD384, bringing the new religion to the kingdom.

I step off the bus at the junction to Duryunsan Provincial Park around noon. The 2.6km walk to Daeheungsa starts at Well-being Food Village, a street of restaurants serving barley mixed with mountain vegetables and other local specialities. The bottles of rice beer that are on display seem superfluous: the heat of the day had already put the whole neighbourhood to sleep.

The road trails along a stream covered by a forest canopy, and families have set up tents next to the limpid water to while the time away in relative coolness.

The first sign that I am in a sacred place is when I turn a bend and catch sight of Daeheungsa’s Stupa Courtyard, a hodgepodge of steles and bell-shaped stones, some looking freshly carved and others weathered illegible. With its densely clustered memorials to great masters from throughout the centuries, it is like an open-air version of London’s Westminster Abbey.

Then, before I know it, I’m passing through the Gate of Liberation – not nirvana, but the temple’s encouragingly named entrance. Spread out before me is an entire temple town, and rising behind it are the heights of Mount Duryunsan, delineated against the powder-blue sky in rocky humps. For the mystically attuned, the sweep of three peaks represents, from south to north, the reclining Buddha’s head, chest and feet.

I stroll across the gravel forecourt to the temple museum, a treasure trove of art and curios ranging from tea cups to bizarrely shaped rocks. On the first floor, a figurine of the baby Buddha challenges my scanty knowledge of infant development. The portly bambino is standing bolt upright, one hand pointing above and the other below, declaring, “In heaven and on earth, I alone am worthy of veneration.”

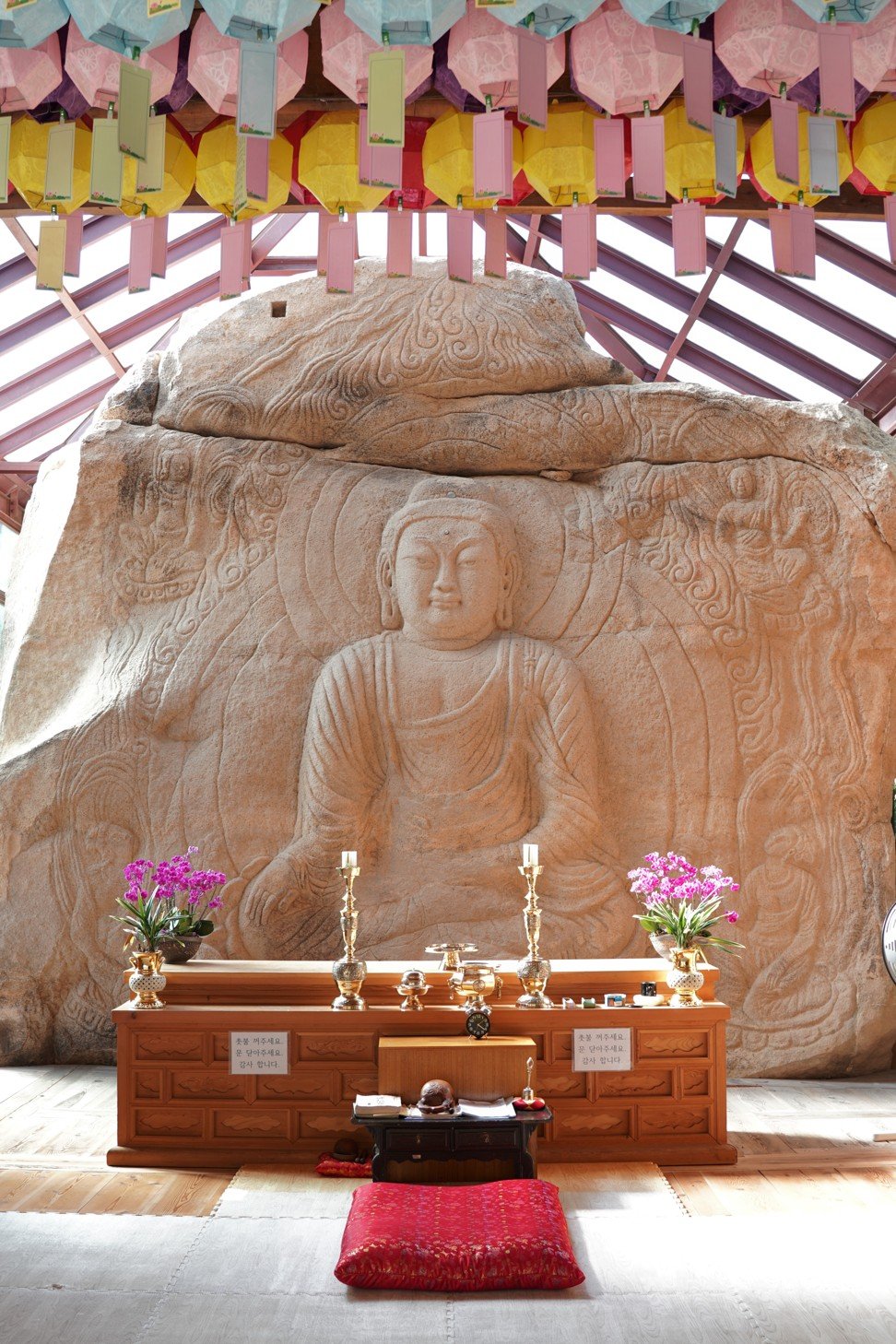

I admire the carving of Maitreya, sitting serene in a womb of aureoles, swirling flames and pennants. Once again, I have the space all to myself – a rare experience at a World Heritage Site

The second floor of the museum chronicles the lives of two of the many Zen masters from Daeheungsa’s history. Master Seosan, born in 1520, went around the country at the age of 73 organising “monk militias” to defend Korea against the invading Japanese. The clergy under his command were unstoppable, proving that in those days men were men and so were monks.

Another towering figure from Daeheungsa was Master Choeui. A Michelangelo of monasticism, Choeui made an impact on painting, calligraphy, poetry, tea ceremony ritual and many other fields. Both masters Seosan and Choeui exited this world while meditating in the full lotus position.

The Chinese island that is so close to Hong Kong, yet very different

On my way out, I ask museum caretaker Lee Ju-seong which of the 45 temple structures are must-sees. I am directed to Daeungjeon Hall, in the North Court, and Cheonbuljeon Hall, in the South Court. I step into the radiant sunshine and the buzzing of insects and head first to Cheonbuljeon, a 200-year-old wooden building with sliding doors of intricate floral latticework, painted smartly in tones of peach and topaz. Two horned dragons beam down at me from the entrance.

Inside are tier upon tier of small white Buddhas – 1,000 in all – each a bit different from the rest. Alone with the statuettes in the still alcove, I contemplate their unlikely journey from a jadestone quarry in southeast Korea.

After being loaded onto a ship in 1817, the sacred payload was blown off course by a storm and ended up in Japan, where it became stuck in customs. In Odyssean fashion, the Buddhas were then buffeted from one port to another before reaching Daeheungsa in 1818.

After paying my respects to the golden Buddhas in the North Court, I head up the mountain to see the main attraction. Passing through the dense, humid forest, I let my thoughts run their course, focusing on my footwork. Sun spots mingle with leaf shadows as I step from mossy stones to ochre patches of clay.

Half an hour later, I’m beetroot-red and doused in sweat, but have managed to reach Bukmireukam Hermitage. A grey-robed monk is sitting on a stoop, unfazed by my arrival, while two Korean Jindo hunting dogs strain towards me on their chains.

One terrace higher, a prayer hall extends from the side of a boulder, protecting an 11th-century carving of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. I admire the looming figure, sitting serene in a womb of aureoles, swirling flames and pennants. Once again, I have the space all to myself – a rare experience at a World Heritage Site.

Feeling awestruck, I head back down. I’m just about to pass back through the Gate of Liberation when the hanging temple bell is struck with a swinging beam. The sonic resonance floods the air like a gentle thunderclap, bringing on a pleasant full-body sensation.

During the walk back to the bus stop, I fall in with a trio of middle-aged schoolmistresses from Gwangju, the provincial capital. One of them, I learn, has a grown son. I ask if she has any child-rearing advice to offer.

“Give him freedom,” she says. I’ll ponder this along with the day’s discoveries during the ride back to Seoul, and perhaps in the years ahead.

Getting there: From Seoul, take a train to Mokpo or Gwangju; tickets can be reserved at letskorail.com. Next, take an intercity bus to Haenam County and then transfer to a local bus bound for Daeheungsa. Alternatively, take a bus straight from Seoul’s Express Bus Terminal to Haenam.

Staying there: To experience Daeheungsa as an insider, arrange a temple stay by calling (82) (61) 535-5775. The nearby Land’s End Village has a range of accommodation, from hotels to minbak (homestays), and Songho Beach has a pleasant camping area among a stand of black pine.

Why Busan is the best place to visit, topping Lonely Planet 2018 list

What to do: For more culture and hiking, head to Mihwangsa Temple and Mount Dalmasan, just south of Mount Duryunsan. At Land’s End Village, take the monorail or the steps up to the hilltop monument, walk the cliffside path to Land’s End Tower, and enjoy the fresh seafood near the harbour. From the village, ferries depart for Bogildo Island, which is renowned for Yunseondo Grove – very possibly Korea’s most impressive traditional garden. Ferries also service Wando Island, and from there it’s a short bus ride to Myeongsashimni Beach, one of the country’s longest.