Six ways Japanese women can deter gropers on trains and sexual harassment, from stickers to stamps

- Sexual assault is so common on Japanese public transport that IT firms and even stationers offer solutions

- Audible phone camera clicks, stamps, stickers and apps are among the innovations

A stationery maker has joined the war against groping on Japanese public transport with a stamp that marks perpetrators with a special ink.

Invisible to the naked eye, a temporary hand-shaped design appears when a UV light is shone on the area. Nagoya-based company Shachihata said its new product could be used to identify culprits, though it was not immediately clear how long the ink would last.

A limited supply of 500 of the 9mm-wide “anti-nuisance” stamps, priced at around US$25 (HK$200), sold out within an hour of launch on August 27.

Company spokesman Hirofumi Mukai said the product was designed primarily as a deterrent to gropers – the stamp comes with a strap that can be attached to a bag to signify the wearer is carrying the device, according to the Japan Times.

The company began developing the stamp in response to a viral tweet in May in which a woman suggested using a safety pin to spike gropers’ wandering hands. “We will continue to consider ways for us to contribute to society,” the company tweeted.

Anyone convicted of groping in Japan can face a prison term of up to six months or a fine of up to 500,000 yen (US$4,500). The sentence can rise to a 10-year term if the incident involves violence or threats.

In a famously anti-confrontational country where stoicism – even in the face of personal danger – is a socially conditioned response, numerous inventive ways have been found by public transport providers, police and victims themselves to deter or publicly shame those who grope, harass, or assault others on trains.

Anti-harassment campaigners criticise these methods, which include alarms and apps, as sticking plaster solutions that do little to address the roots of the problem, such as by boosting men’s education around the subject of harassment and breaking taboos around reporting incidents.

Earlier this year, WeToo Japan, the crowdfunded Japanese arm of the global #MeToo movement, surveyed 12,000 people between 15 and 49 living within the Tokyo area on the subject of harassment, including on trains.

Nearly half of the female respondents reported “unwanted touching” (compared to just 9 per cent of men), while around a fifth had witnessed indecent exposure.

Here are five more ways Japan has tried to reduce molesting in public.

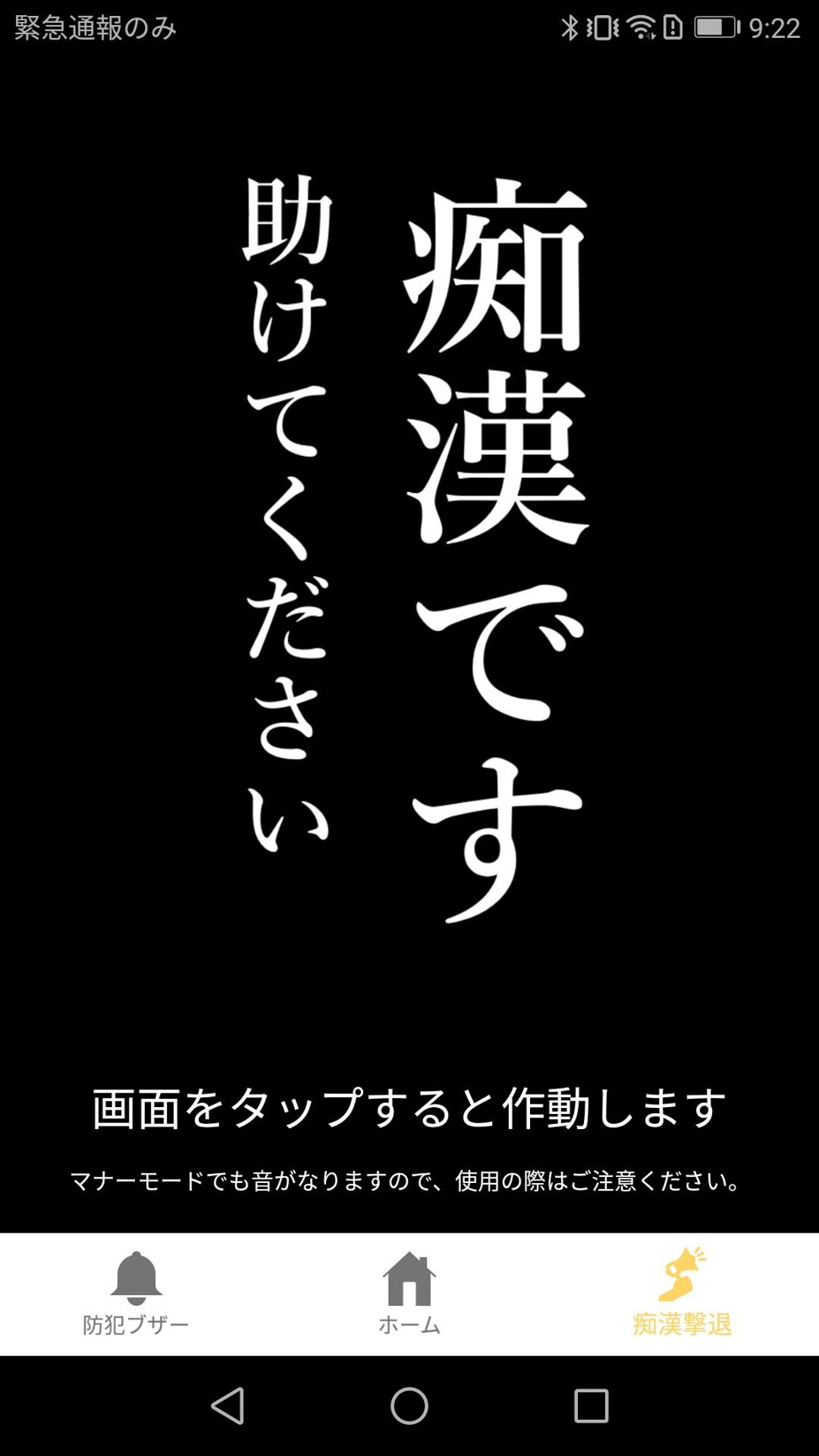

DigiPolice app

The government developed app now features a “repel groper” icon that, when tapped, first displays a message saying “There is a groper here. Please help” to show discreetly to fellow passengers, before blaring out a recording that repeats “Please stop” with a red warning icon on the screen.

The app also automatically notifies a designated email address, allowing victims to communicate their distress with someone they trust.

Since the update was issued, the app has been downloaded hundreds of thousands of times.

Women-only carriages

As well as surveillance cameras, which help catch perpetrators, Tokyo’s train network is also famed for its “women-only” carriages, which men are barred from occupying during the busiest commuter hours.

While commuters largely welcomed the change, others feared that if a woman entered a mixed carriage she would be seen as a willing victim.

Japan’s Mainichi newspaper wrote in 2005: “Women-only carriages have had to be created because some people unforgivably use packed trains to commit sexual assault. This cannot be said to be the result of a dignified civilisation.”

Phone camera sounds

A country famed for its technological innovation, Japan was among the earliest adopters of camera phones worldwide. Unfortunately, the convenience of having a camera within a mobile phone also gave rise to sneakier forms of misdeed on public transport, such as upskirting – in which offenders angle cameras to take photos underneath women’s skirts – and other forms of secret photography.

In 2011, the government ruled that all phones sold in Japan must deploy an audible shutter sound whenever a photo was taken and that built-in cameras could not be muted.

Phone companies, even foreign makers such as Samsung and Apple, have complied, but covert photography remains an issue thanks to handsets imported from abroad and apps that circumvent the rules.

Anti-groping badges and stickers

In 2015, police in Saitama prefecture deployed a strategy for reducing groping on commutes – stickers. Designed to be applied to mobile phones, the small stickers use a peel-off upper layer that, when pressed against skin, leaves a red “X” mark in ink, effectively branding the culprit until they wash it off.

The campaign was launched in tandem with a series of cartoon posters designed to reduce harassment in an area where around 2,000 groping reports are made each year.

In 2016, anti groping badges were distributed at stations in Tokyo and Osaka which read, “I won’t let the matter drop” and, “groping is a crime”. They were designed by a student and her mother to ward off attackers in response to the statistic that 89.1 per cent of victims did not report incidents.

Chikan Radar

Using the website Chikan Radar on their phones, victims can record harassment and tag the incident to a specific location, displayed on a shared map for all users to see, that warns others of a predator in the area. If users register on the website using the chat app Line, they can receive data from the previous day as well.

Since its launch this month by the female-owned IT firm QCCCA, which also runs a harassment consultation website, Chikan Radar has collected more than 500 reports about issues ranging from secret photography to flashers.

Once the site has collected a large amount of data, its makers will go to police and demand greater protection for victims of public transport assault.

“I want the accumulation of this data to be helpful with prevention measures to lead to the eradication of molestation,” founder Nari Woo tweeted.