Pride & joy

The Shining Jazzy Chorus is thriving, giving voice to Beijing's LGBT community and proving that Chinese society is becoming more accepting, writes Laura Fitch

Low murmurs rise from the auditorium of a small, packed independent theatre tucked away on a tiny side street behind Beijing's National Drama Academy, hidden from the bustle of tourists on Nanluoguxiang hutong. At the urging of a man on stage, mobile phones are pulled from pockets and turned off. The lights dim and a row of men file in under them, taking their places as people in the crowd hush one another with hisses and slight, dry coughs.

For the next two hours the audience is treated to a musical variety show featuring duets, solos, thumping modern dance numbers and heartfelt chorus singing.

Ladies and gentlemen, the Shining Jazzy Chorus has arrived.

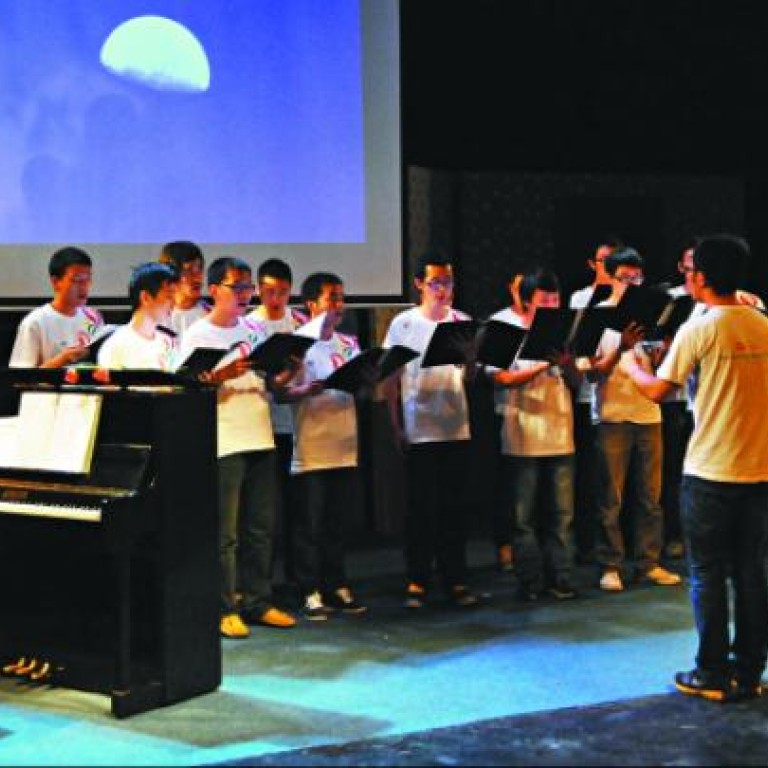

Augmented by two guest groups, this October performance marked the choir's fourth anniversary, and the first time it has performed for the general public, rather than an audience drawn exclusively from the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community.

The Shining Jazzy Chorus is the only choir in Greater China registered with the international Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses and, according to its members, is the only gay choir in the country.

Begun in 2008 in the then newly opened Beijing LGBT Centre, with a handful of amateur singers and a professional musician as a volunteer coach, the choir, which now boasts roughly 20 members, a weekly rehearsal schedule and a CD - recorded at the fourth anniversary performance - has grown in tandem with Beijing's LGBT civil society.

When Beijing LGBT Centre adviser Stephen Leonelli landed in the capital, in 2009, he found a nascent LGBT community beginning to take shape. The centre had opened its doors the previous year, but groups devoted to promoting LGBT rights and providing community support were few. Now there are 12 to 13 groups in Beijing alone, he says, including a chapter of the Guangzhou-based PFLAG China (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) and BGLAD (Beijing Gay, Lesbian and Allies Discussion). Lalas (slang for lesbian) gather at the Beijing Lesbian Centre while ("comrade" and slang for "homosexual") of all persuasions join the Beijing LGBT Centre's various social programmes, watching movies together, conversing in English, debating literature in a book group or just hanging out.

Cinephiles get their fix at the biannual Beijing Queer Film Festival and the founder of China Queer Independent Films, prolific gay film director Fan Popo, takes the show on the road, screening LGBT films in cities across the country. Magazines such as and provide coverage and last month saw the inaugural China Rainbow Media Awards, an honour bestowed on Chinese journalists and publications that provide fair and balanced reporting of LGBT issues.

The seeds were planted in 2003, she says, when the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria began funnelling money into establishing HIV-Aids groups in the mainland. These groups focused on health and prevention issues but had little to do with anti-discrimination efforts or social support, activities she had seen in action in the US. Though often disbanding at the end of a project or when the funds dried up, the HIV-Aids groups nonetheless taught people how to mobilise, says Bin: those involved in the groups began to see the potential of using similar organisational models to start up rights and social groups.

"For the past 10 years, for the LGBT organisations, it's been a process of self-empowerment, self-education and self-help, basically," she says.

When the LGBT Centre management hired its first staff member, in 2008, they were worried about paying him, says Bin. The centre now has three full-time staff members (paid through a mix of donations and funds raised by other means), a busy social calendar and seven volunteer psychotherapists, who, Leonelli says, have helped more than 400 people in private and group therapy sessions.

The scope of initiatives has broadened, too. Groups such as Tongyu are working with schools - educating teachers on how to handle LGBT students, as well as informing others about the community and engaging in mental-health work, she says.

It was these advances in the capital that piqued the interest of 29-year-old Wang Ruoyu. While working in an office in Shenzhen, Wang surfed the internet, looking for groups of interest to join. He was impressed by the line-up of Beijing LGBT organisations he saw represented at Hong Kong's first Pride Parade, in 2008, which he attended. He enjoyed singing, so he took a shot at finding a gay choir and ended up connecting with the Shining Jazzy Chorus.

"I was deeply attracted by the LGBT culture in Beijing," says Wang. That became a key factor in his moving to the capital in 2010. Less than 24 hours after his plane touched down, he was at his first rehearsal. A change in the schedule meant Wang arrived just as the chorus was wrapping up, but he instantly liked the camaraderie of the group.

"The director gave me some dance moves to practice rhythm," he says. He was hooked.

Wang is now involved in the LGBT Centre and a group making LGBT documentaries, and helps organise Shining Jazzy Chorus rehearsals and performances. He says he hopes one day the chorus will be able to tour the country. In 2011, he joined the Pride Parade in Hong Kong as a representative of the chorus, though he didn't perform.

"I like the feeling of singing with people, the feeling of two harmonies matching," he says. "That's not something just one person can do."

in a basement karaoke parlour just off the busy West Third Ring Road, in Haidian district. Clustered together on a small black sofa facing two flat-screen televisions broadcasting cheesy Christmas videos, a group of eight singers - five men and three women - grip sheet music and turn watchful eyes to 30-year-old Fei, who is leading them through voice warm-ups using a Smartphone tuning app.

"Do …," he sings, motioning with his hand for the singers to follow.

"Do …," they sing back to him.

"Do, re, mi …"

"Do, re, mi …"

"Not like that, like this," Fei says, and sings the intro to .

On a long table, goji berries float in a pot of chrysanthemum tea next to pink and yellow tambourines, microphones and juice bottles. Pounding bass emanating from other rooms bursts in every time the door is opened. As they continue to sing, the group find a groove. Hands start to clap to the rhythm; feet tap out the beat. As their voices gain confidence, the sound swells.

"Singing is a way of communicating," says acting choirmaster Fei. "There's a wall inside everyone's mind. That wall is there when you are trying to just express yourself in another way rather than talking or writing.

"When you climb the wall, and jump over it, you become a completely different person."

Fei first scaled that wall when he was a university student in Kiev, Ukraine, during a spring festival concert: "The first half, when I sang, I was just hiding behind the wall. But then I noticed people weren't laughing. They were paying attention. And I just climbed the wall."

Returning to Beijing after graduating, Fei found he was no longer scared of speaking his mind.

"I want everyone around me to feel like that," he says.

To its members - some of whom have not "come out" in public about their sexual orientation - the Shining Jazzy Chorus provides an opportunity to indulge in a love for music and make social connections without disguising their sexuality, something they may not be able to do comfortably in other facets of their lives.

Still, who prefers not to use his real name as he has yet to come out, joined the chorus in 2009, after finding a posting about the choir on a gay website. His first practice with the chorus made a deep impression. It was the first time he had been around "other people like myself. Not only gay people, but people who love music. People who love life".

"It was really a happy time," he adds.

Outside the karaoke room, Still, who is from Sichuan province, speaks softly and carefully, with his fingertips neatly pressed together. Wearing glasses and a blue and grey argyle jumper over a button-up shirt and jeans, he looks every inch the NGO office worker he is. Not so long ago, the 31-year-old didn't think gay rights had much to do with him, but personal issues have arisen and his parents are increasing the pressure on him to marry.

Still used to think he could never tell his parents he was gay but now, he says, he believes his mother might support him. Society's attitudes are changing, he says: "It's a positive change. There is hope."

The development of a wider civil society in China is very important, he says. Groups devoted to environmental protection - his own speciality - health and education are as important in his worldview as those dedicated to gay rights.

"I'm happy to be part of this," he says.

Homosexuality was a crime in the mainland until as recently as 1997, and listed as a mental illness until 2001. It was only last year that a policy revision allowed homosexuals to donate blood, though the wording still bans men who have sex with other men from giving, says Bin. Public policy may be slow to adapt to change, but perhaps the biggest challenge to coming out for most individuals is their family.

Many parents have a dominant role in the lives of their adult children, and though they may not be anti-gay in the sense that they feel the behaviour itself to be deviant, they see it as a problem.

"It's not that you are a bad person, or are going to hell," says Bin. "It's that you have to go into a heterosexual marriage, have children and carry on the family line."

In the year and a half since the LGBT Centre introduced its psychotherapy programme, "the No1 thing we've seen in people coming in is family pressure", says Leonelli. People feel guilty about not having children, and keeping a core aspect of themselves hidden from friends and family can lead to depression and anxiety.

Leonelli recounts an instance at the Beijing LGBT Centre when the mother of a young female volunteer travelled to Beijing from Inner Mongolia after her daughter had refused to see a psychologist who claimed that homosexuality was a mental condition that could be reversed. Hysterically hitting herself, she accused those at the centre of ruining her daughter's mind.

"It was hard for me to watch," he says. "I can only imagine what it's like for the daughter."

For the most part, coming out remains a luxury reserved for young, unmarried people who are financially independent and well educated, says Bin.

For people in rural areas, especially lesbians, who are dependent on family, the pressure to marry is heavy.

"If they dare to come out, they will be labelled a monster, a pervert," Bin adds.

"I finally understood," she says, of reading his blog. "He didn't choose this life. It chose him."

She has written numerous articles on the topic, as well as a book, , the first on the mainland to be legally published with " " in the title. Last year, the book was released in Taiwan. Lu is currently penning another. She sees her role as being a bridge between parents, whose thinking she understands, their gay children, with whom she sympathises, and the public, whom she wants to help understand what being involves. At times, gays and lesbians will ask her to go with them to speak to their parents.

A small but growing number of people think like Lu, especially in major urban centres. It's increasingly common for people to have gay friends, says Still, and the term , or "gay friend", has joined the lexicon over the past two years.

The Shining Jazzy Chorus is looking to move on to bigger and brighter challenges. After the success of the chorus' fourth anniversary, Wang is hoping for more performances, in front of both LGBT and straight audiences, while Fei is looking to challenge the group's vocal skills so they can sing longer and louder.

"Maybe in the future we can choose harder pieces, maybe a capella," he says, with a smile. "Just the pure power of us."