It’s ‘a losing battle’ against abandoned fishing nets but he’s fighting anyway: meet Hong Kong’s ‘ghost net hunter’

- Harry Chan is known as Hong Kong’s ‘ghost net hunter’ for his work clearing the city’s waterways of ‘ghost nets’ – fishing nets that have been abandoned

- He reveals why his parents almost sold him as a baby, business booms and busts, and how he fell in love with diving and beach clean-ups

During the historical changes in China in 1949, my grandfather, parents and eldest brother moved from Yantai, in Shandong, to Hong Kong. When I was born, in 1953, my family was sharing an old stone house in Diamond Hill in Kowloon with other families from Shandong.

I cried all the time as a young child because I was so hungry. My parents almost sold me to someone so that I could eat, but my grandfather refused to let them because I was the second grandson. He didn’t speak Cantonese, but he was a kung fu teacher and made a little money from that.

I’m the second eldest of seven kids – four boys and three girls. Two of my sisters passed away soon after they were born.

Handsome dad

My dad got a job in a factory. He didn’t look like a typical factory worker, he was handsome and had clean fingernails.

The factory owner was from Shanghai and illiterate. He asked my father if he could read to him. So, my father began reading the newspaper to him every day.

One day, the boss was offered a job making plastic watch straps for a client in the Middle East. He turned it down because there wasn’t enough profit in it for him but asked my father if he wanted to take the job and even supported him to set up a factory.

Too cool for school

By the time I was four, my father had a factory in Cheung Sha Wan, in Kowloon, making plastic flowers. By 1960, he was one of the four big plastic flower producers in Hong Kong. Later, he opened a factory in Taipei because he had a lot of relatives in Taiwan.

I didn’t enjoy it at all. I cried a lot and wet my bed. I tried all sorts of things to try to get out of school. One time, I said I was sick and put warm water in my mouth so that when they checked my temperature, they thought I had a fever and sent me to the hospital in Happy Valley.

When I was given a test, I just put my name on the paper but didn’t answer the questions. Despite my best efforts to get expelled, I was at the school for six years until the headmaster finally let me go.

Time for tea and scones

Because my report card was so bad, it was hard to get accepted into another school. By this time, my family had moved into a house on Kimberley Road in Kowloon. Luckily, I was accepted into Moral Training English College.

I immediately liked it because there were so many girls. I got HK$5 or HK$10 pocket money a day, which in the 1960s was a lot, so at breaktime I bought bottles of Coca-Cola for the girls.

After two years, a schoolmate said he was moving to boarding school in the UK and suggested I go, too. I arrived at King’s College in Taunton in 1968.

He was kind and one thing he said has stuck with me: “In the future, whatever you do, make sure that you contribute back to the community.” But at the time, I just thought about wanting to leave.

I could only get out with my parents’ consent. So, I told my mum I’d been caught smoking and was going to get expelled, and to write a letter to the headmaster saying I needed to be with my brother in Manchester.

To catch a thief

I moved with my brother to London and we stayed in Earl’s Court and South Kensington. I got a part-time job in Carnaby Street for a few weeks and then went back to Manchester and stayed with a school friend.

In Manchester, I changed from one technical college to another. I only went to the school for lunch or to date girls, which is how I learned English.

My father’s business wasn’t doing too well, so I came back to Hong Kong in 1972. I didn’t finish my OND (ordinary national diploma). I worked in his assembly centre in Sai Kung in the New Territories and then went to live in my dad’s apartment beside his factory in Kaohsiung.

I learned a lot at the factory and became a sort of manager. There was a problem with the workers stealing the plastic flowers. I asked the foreman to check everyone’s bag as they left work. One of the workers told me who was organising the theft.

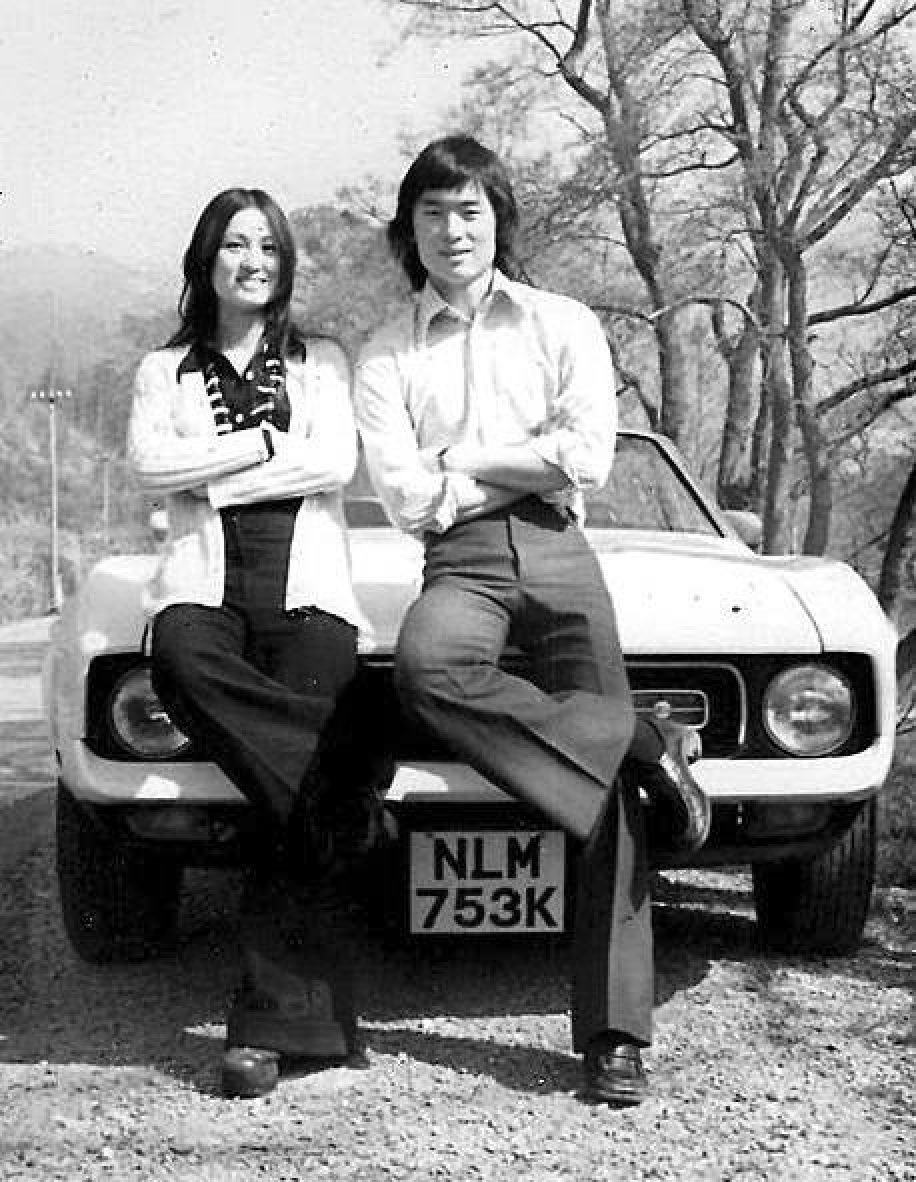

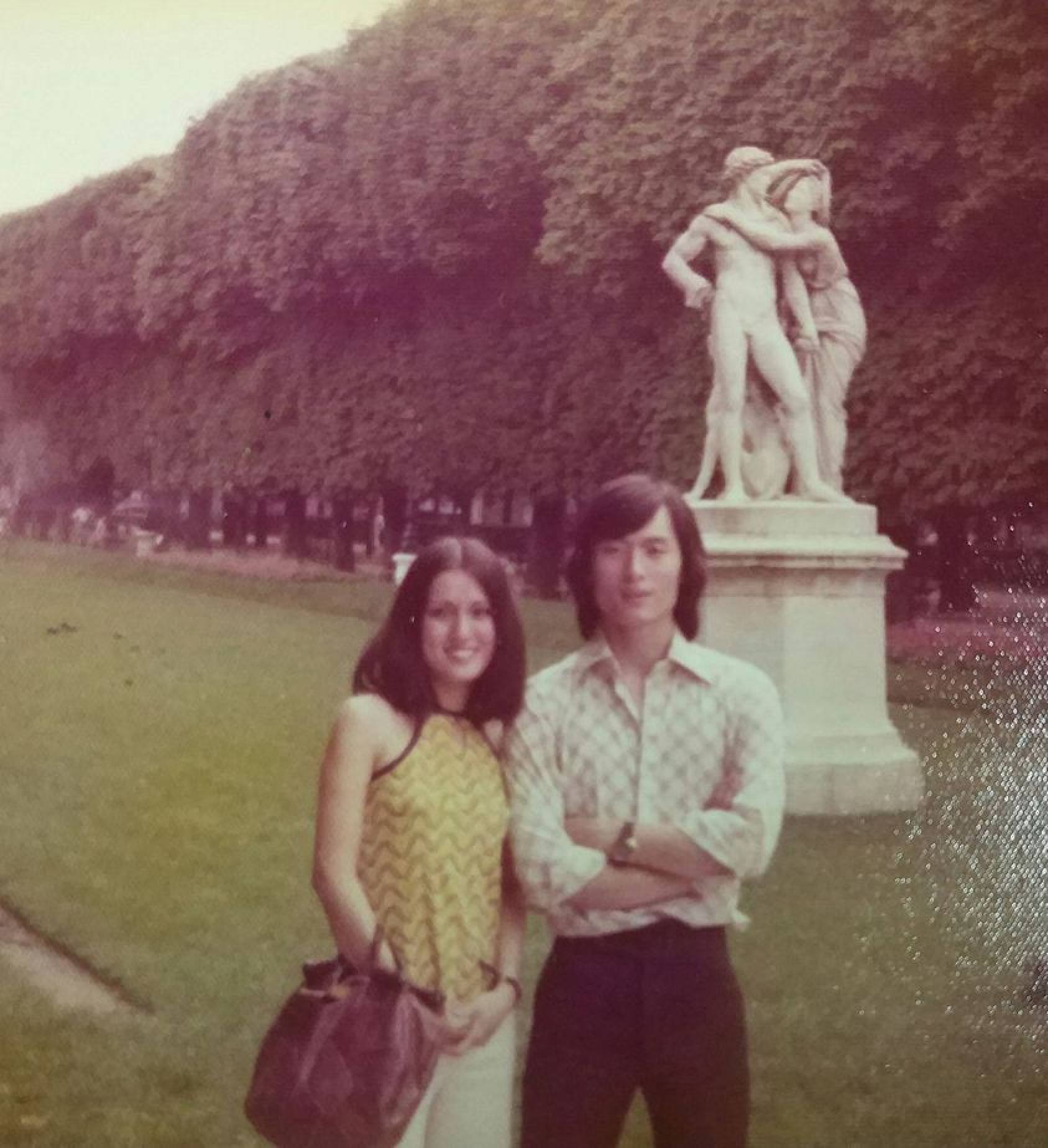

It was at that factory that I met my wife, Melody. She was my father’s secretary and four years older than me.

Putting a ring on it

After a year, I went back to Manchester to complete my diploma. When my brother returned to Hong Kong, it was just me in the apartment and I was lonely, especially in winter when it was snowing. I wanted someone to keep me company.

I started writing to Melody and asked her to move to the UK. Finally, she quit her job and moved. Two months later, on my 21st birthday, we got married. I didn’t have the money to buy her a fancy ring, I just got her a stainless-steel one. It proved to me that she really loved me.

Half-baked dreams

I called my mum the day before I got married and she didn’t approve because Melody was older than me. She told me I’d regret it, but we’ve been married 50 years.

My parents’ business was getting bad because the market changed from plastic flowers to polyester flowers. They couldn’t send me any more money. I worked a series of jobs in Manchester until 1982, mostly in F&B – I got a job at Golden Egg, a 24-hour restaurant, and in a casino.

I thought working in a restaurant I might learn how to cook and one day I could open a little shop, but it didn’t turn out that way.

China opens

In 1982, I came back to Hong Kong, leaving my wife and son in the UK. China was opening up and my father went to the mainland to do business. He had been really struggling before, but in China he began making wicker baskets and the business took off, he was shipping more than 100 containers of wicker baskets a month.

At first, the Chinese I worked with were suspicious of me as someone who’d been living in the UK for a long time. My father advised me to keep my head down and do my work. After a year, I was accepted and trusted.

I decided to stay and asked my wife and son to join me in Hong Kong. I learned a lot in that time about how things worked in China. Business went smoothly and I got more customers and bigger orders.

Smoker’s lungs

I met up with a schoolmate from Manchester who was back in Hong Kong and in the property business. He had a yacht and asked me to join him to go sailing. I didn’t enjoy sitting around on the boat, so one day he brought along four sets of diving gear. I did my first dive with him in 1987.

In the beginning, we didn’t realise how dangerous diving could be. Later, he hired another boatman who was a diver and taught us the basics. We went spearfishing around Sai Kung. I started going on dive trips around Asia with my old schoolmate.

Rash and trash

By the late 1990s, people were talking about how China would open up fast. My father was about 80 and decided to retire in China, and later they moved to Canada. I decided to keep the company going, but in 2010 I lost the business because customers could go direct to the supplier and didn’t need a middleman.

I was depressed. I quit smoking and immediately came out in a rash all over my body.

A deep sense of peace

Cleaning up the beach and the underwater area is a great way to improve your mood and interact with people of different ages, cultures and religions. It is beneficial for your body and mind.

I love diving. It is so quiet and peaceful under the water. You see the beauty of the ocean and also how people dirty it. I do dives to collect ghost nets and beach clean-ups with different groups, NGOs and companies about once a week.

Seven years ago, I dived with a disabled diver, he had no legs. We went down to collect fishing nets. I saw how doing an underwater clean-up benefited him. Since then I’ve dived regularly with disabled divers. They are able to move much more freely in the water.

Giving back

I often think back to my housemaster’s advice. The work that I do now, even though it is not paid, I see as investing in something of value. We are fighting a losing battle, but at least I have raised awareness and the word is spreading globally.

I go to schools to give talks and see the students are interested in environmental issues. I’ve told my wife that if even I get caught in a ghost net, please don’t cry, just be proud of your man.

I enjoy what I’m doing. People from the north have heard about my work and I will be starting my Greater Bay Area clean-up in April. We will use our influence to try to reduce problems such as trawling.