- 1,500 works, including a collection of ancient pots painted over by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, are on view in the first exhibitions at Hong Kong’s M+ museum

For its opening exhibitions, Hong Kong’s M+ museum of visual culture has chosen about 1,500 works from its collection of 6,413 pieces. These can be found in 33 galleries spread across 17,000 square metres (183,000 square feet) of display space.

Whitewash (1995-2000), by Ai Weiwei

He has often used ancient artefacts in his work to question the value we place on tradition, such as by photographing himself dropping and smashing a 2,000-year-old Han dynasty urn, or by adding a Coca-Cola logo to an equally old jar as a comment on globalisation.

2/F, Sigg Galleries

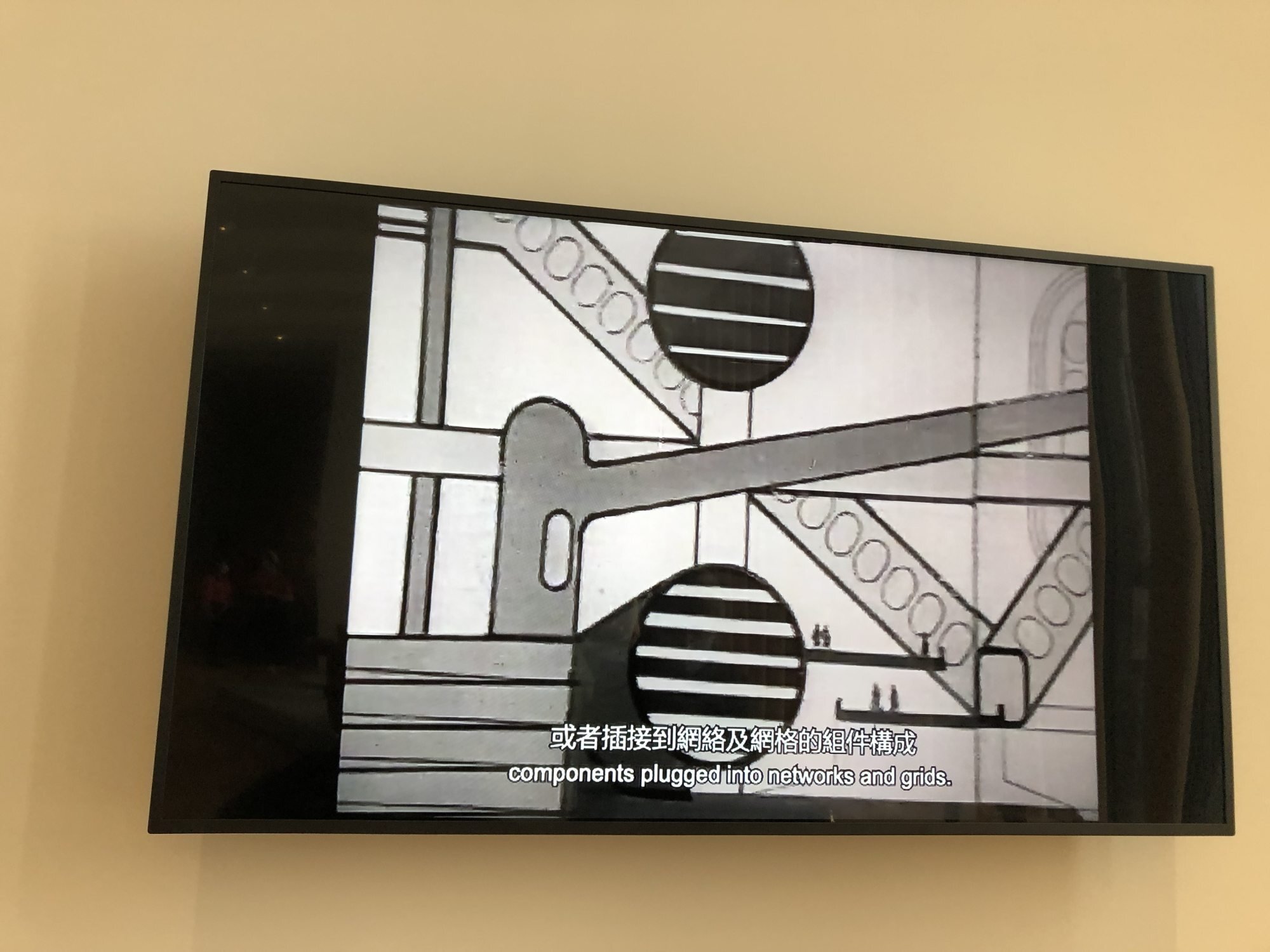

The Archigram Archive

In 2019, M+ bought the entire archive of the 1960s London-based architectural practice. It is packed full of ideas and images about living in dense, technologically advanced cities of the future, such as Hong Kong today. A selection of its models and drawings are on view, including a whimsical but convincing “walking city”, accompanied by a 1967 BBC documentary.

Nearby, a vast mural by the Beijing-based Drawing Architecture Studio turns Archigram’s visions into a spectacular “Where’s Wally”-like map of architectural projects around Asia.

2/F, East Galleries

Asian Field (2003), by Antony Gormley

The result – which toured four Chinese cities in 2003 – is a miniature terracotta army of unique creatures all staring back at you.

2/F, West Gallery

Time Traveller (2014), by Sara Tse Suk-ting

When her mother died, the Hong Kong artist used porcelain clay to preserve the shapes of objects that she had used: a ball of string, a hat, a scarf, her diary. These are displayed together with real pieces of furniture and an old-fashioned sewing machine as a series of tableaus. This is not only the preservation of memory; the porcelain underscores the fragility of memory – when the clay was fired, the items encased within were cremated and destroyed.

G/F, Main Hall Gallery

Braiding (1998), by Lin Tianmiao

Twenty-three years ago, Chinese artist Lin Tianmiao made this multimedia work at her home in Beijing that speaks to today’s debate about sex and gender identities. Lin is a sculptor whose labour-intensive installations often question how the female body and “women’s work” are viewed in society.

The first thing viewers will see is a large, slightly blurry, androgynous photograph of the artist with her head shaven. Countless threads stitched across her face extend from the back of the canvas and are woven into a long braid that ends at a small video screen showing a pair of hands braiding three threads.

2/F, Sigg Galleries

Rattan Chair (1950s-60s), by Kowloon Rattan Ware Co

One of the museum’s core missions is to redefine visual culture as something that includes what used to be dismissed as mundane, everyday objects. This simple, yet perfect, factory-produced chair is included in the design and architecture galleries. It is part of an exhibition about how design elevated consumer objects in significant moments of rupture in Asia, such as the post-war economic boom.

2/F, East Galleries

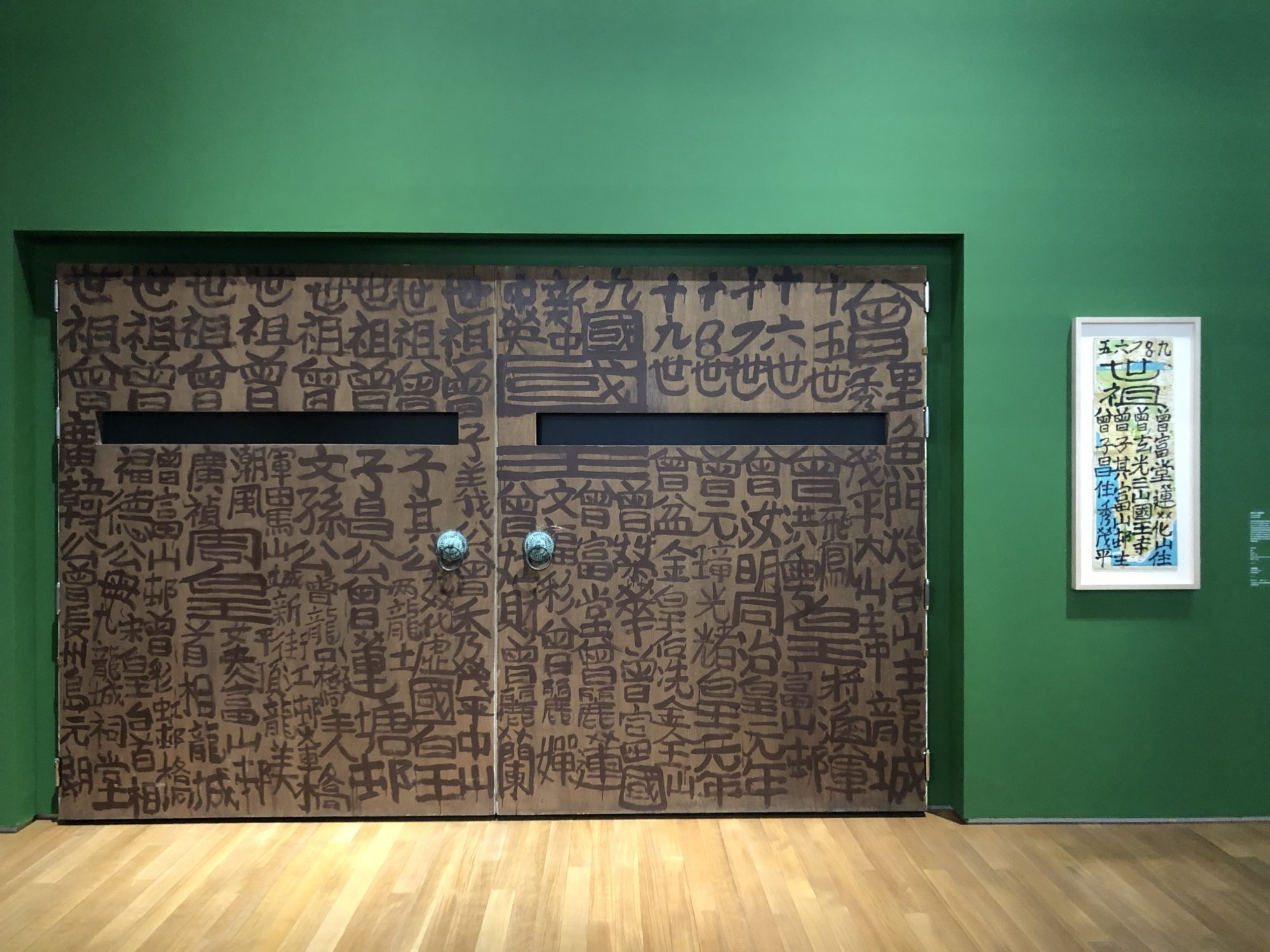

Untitled pair of doors (2003), by Tsang Tsou-choi (aka the King of Kowloon)

At the same time, we can also ask if Tsang’s works risk being empty symbols and clichés now that they are mostly seen away from their original context.

G/F, Main Hall Gallery

We The People (detail) (2011-16), by Danh Vo

The 260 pieces of We The People were fabricated in China and not intended to be exhibited together as a complete sculpture. It appears to show that democracy is always a work in progress.

B2, Found Space

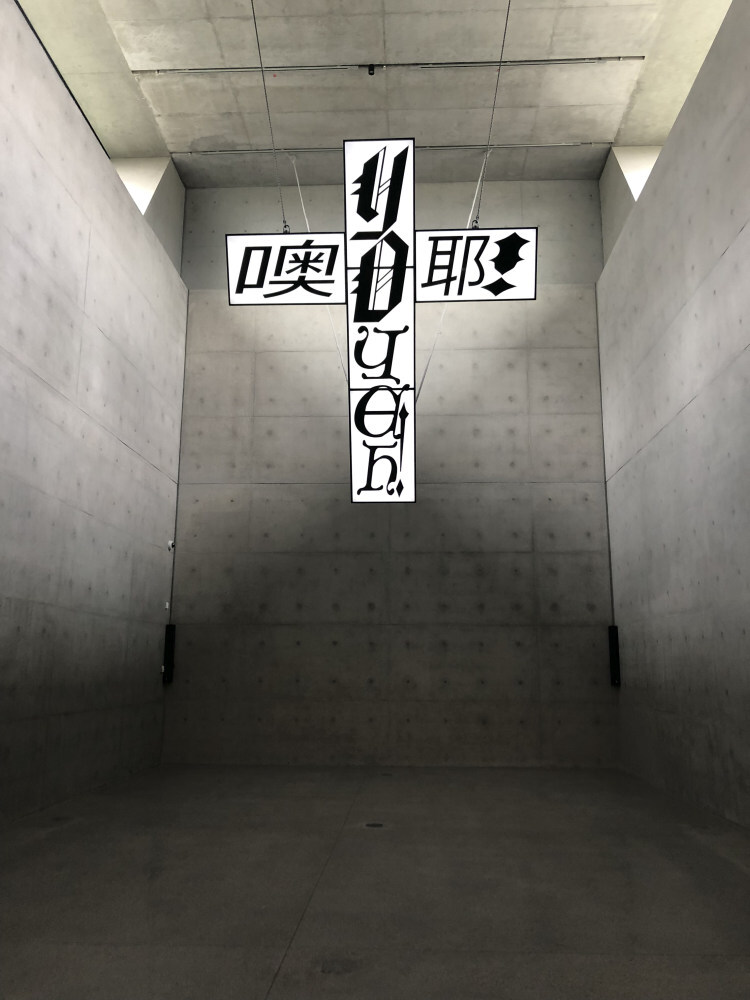

Crucified TVs – Not a Prayer in Heaven (2021), by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries

This work by Korean artist duo Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries is the only art on show in the Focus Gallery. The crucifix is made up of digital screens, with phrases in written Cantonese such as “Ho Yeh”, meaning hurrah, and in English (“Oh Yeah!”) flashing through the video displays with a semi-human chorus blaring out from speakers.

The perfect Instagram spectacle is suitably celebratory and a great showcase for the artists after M+ acquired their entire output in 2018, including future creations that have yet to be conceived.

2/F, Focus Gallery

RMB City (2007-2011), by Cao Fei

A futuristic space sectioned off from the rest of the design and architecture galleries presents Chinese artist Cao Fei’s seminal series in its full glory. Created in Second Life, an early online application that allows people to make avatars and their own imagined digital world, Cao’s fictional city is, according to her avatar China Tracy, “a condensed incarnation” of all contemporary Chinese cities.

2/F, East Galleries