What would Shanghai or Tokyo look like almost empty? How a Taiwanese artist found fame by stripping cities of people and traffic, leaving only calm

- Taiwanese artist Tan Teng-pho, known for his depopulated portrayals of cities, met a brutal death and vanished into obscurity – until recent years

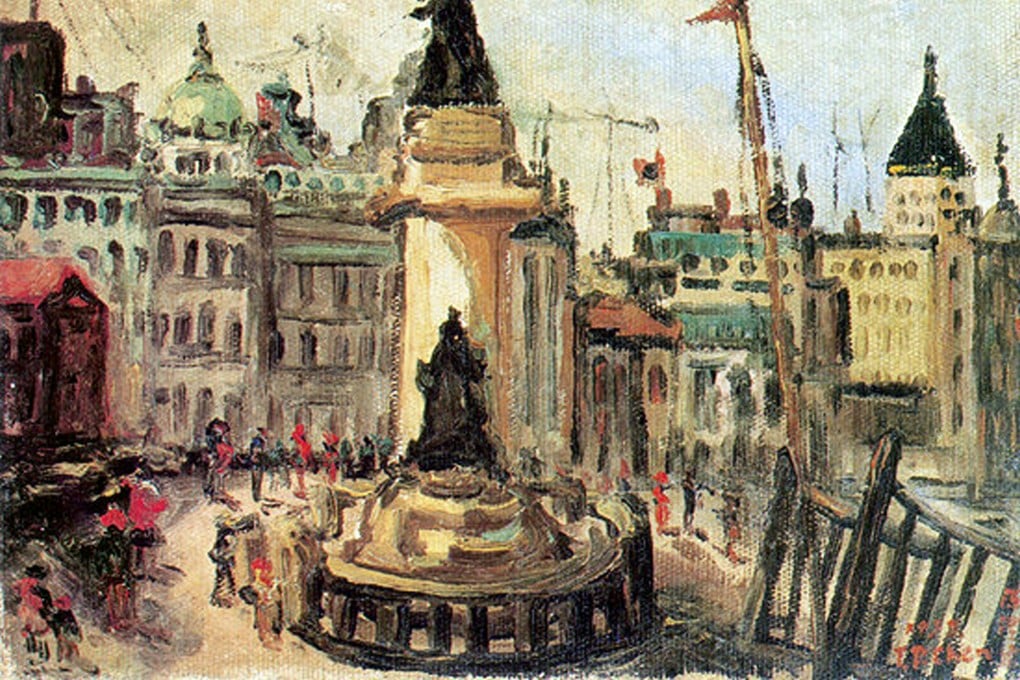

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Tan Teng-pho (alternatively Chen Cheng-Po or Chen Chengbo) was the Taiwanese artistic community’s local boy done good, painting many scenes of the island over three productive decades.

Now he is little remembered outside his birthplace of Taiwan, but the oil paintings he produced while living and working in Shanghai in the early ’30s were his most admired works, and his best-known today.

Tan’s was a life of movement, interacting with the avant garde art worlds of ’20s and ’30s Tokyo and Shanghai while managing to retain a deep involvement with Taiwanese art movements – influencing them as his reputation grew.

He eventually returned home in the mid-30s and met his death in 1947, aged 52, caught up in the anti-government rioting in Taipei that would lead to the island’s independence movement.

Tan then slipped from the art world’s consciousness on both sides of the Taiwan Strait until, in the 1990s and early 2000s, his work began to sell for high prices whenever it came up for auction.

In 2006, at the peak of his revival, Taiwanese art collector and businessman Pierre Chen Tai-ming paid US$4.5 million for Tan’s oil painting Tamsui (1935) – a scene of the Tamsui (Danshui) river and waterfront near Taipei – at the time a world record for an oil painting by an ethnically Chinese artist.