- Nick Tsao talks about the Foster + Partners internship that led to him becoming an architect, learning the art of paper cutting and promoting Hong Kong culture

My parents were both born in Hong Kong and went to boarding school in the UK, where they met while at university. I was born in 1990 and grew up in the shadow of my brother, who is two years older.

My mum is a chef, a private caterer, and my dad is a software engineer. We lived in a house in Chung Hom Kok [on Hong Kong Island]. When I was five, my parents divorced, and I moved with my mum and brother to South Bay Close.

I went to a local primary school in Stanley, St Stephen’s, where we were taught in Cantonese. I was good at art, but we only had one art lesson a week.

Struggling to connect

When I was 12, I switched to West Island School. A lot of the kids already had friendship groups, and, in the beginning, it was a struggle to connect with them on a language and cultural level. We were all probably watching Pokémon, but in different languages.

I found that I didn’t need to spend as much time on maths and Chinese and had a lot more time to spend on art. In addition to art classes, we had a textiles class and design technology, where I built things in wood and plastic. In geography, I built a volcano, and I became quite good with my hands.

He made a minimalist, airy 500 sq ft Hong Kong flat that ‘tells a story’

Foster child

They had a machine with a hot wire down the middle to cut polystyrene. Because I was quite crafty, they asked if I could build the shape of an apartment block.

No one knew how to use the machine and the first day I was really bad at it. I felt self-conscious, in the middle of an open-plan office loudly sanding down a polystyrene block, but I soon got the hang of it. They printed out technical drawings and taught me how to read them.

They were always after something fast, so all the work was done by hand, often using a knife. A colleague called me a human 3D printer.

Second home

The Foster + Partners office was in Cyberport [on Hong Kong Island] and I sometimes worked there after school. After a while, they began paying me. That two-week internship turned into a job every summer and Christmas holiday right through to my university years.

After five years of model-making, I learned their software programs and could help in some ways. On and off, I was at Foster + Partners for 14 years, and only left there two years ago.

A lot of the people there have watched me grow up; it feels like a second home.

My mum’s friends had been giving me Christmas presents and lai see for years, and I enjoyed giving them something backNick Tsao

Most of the architects I spoke to there told me not to study architecture – that was the standard response. But I could see that they worked late hours not because they had to but because they enjoyed it and believed in it.

It is a tough path – it takes a minimum of seven years to get your licence. Compared with other fields that require that much study, like medicine, it doesn’t have the same money and prestige. You do it because you find it interesting and believe that the work is worthwhile.

The great British cook-off

In 2009, I went to Cambridge University (in Britain) to study architecture. It was a small town and I enjoyed the experience of living in that bubble. The lifestyle was about a bunch of friends learning to cook in a dorm room.

We had three eight-week terms and, the rest of the year, I worked at Foster + Partners in Hong Kong, using that money to pay for my flights to and from the UK.

Sleeping at school

I graduated in 2012 and my (Foster + Partners) boss sent me to an interview at the Beijing office. I got the job and signed a contract. I was keen to go, I wanted to improve my Mandarin and was interested in the culture, but the Beijing government denied my visa. As it was a professional job, I needed a master’s degree.

I worked for the architecture firm Benoy for a year, which was mostly retail and shopping malls, and then began a two-year master’s. I chose Chinese University [of Hong Kong] over the University of Hong Kong because the projects they focus on are more Hong Kong-based, and I wanted to reconnect with the culture.

I struggled for the first few months to make friends in Cantonese. Because it was a long trek from my mum’s in Repulse Bay to Sha Tin [in the New Territories], I started sleeping on a fold-up bed that I kept under my desk in the studio.

Technically, this wasn’t allowed, but there were a few of us who did this Monday to Friday and we became friends.

Cutting it

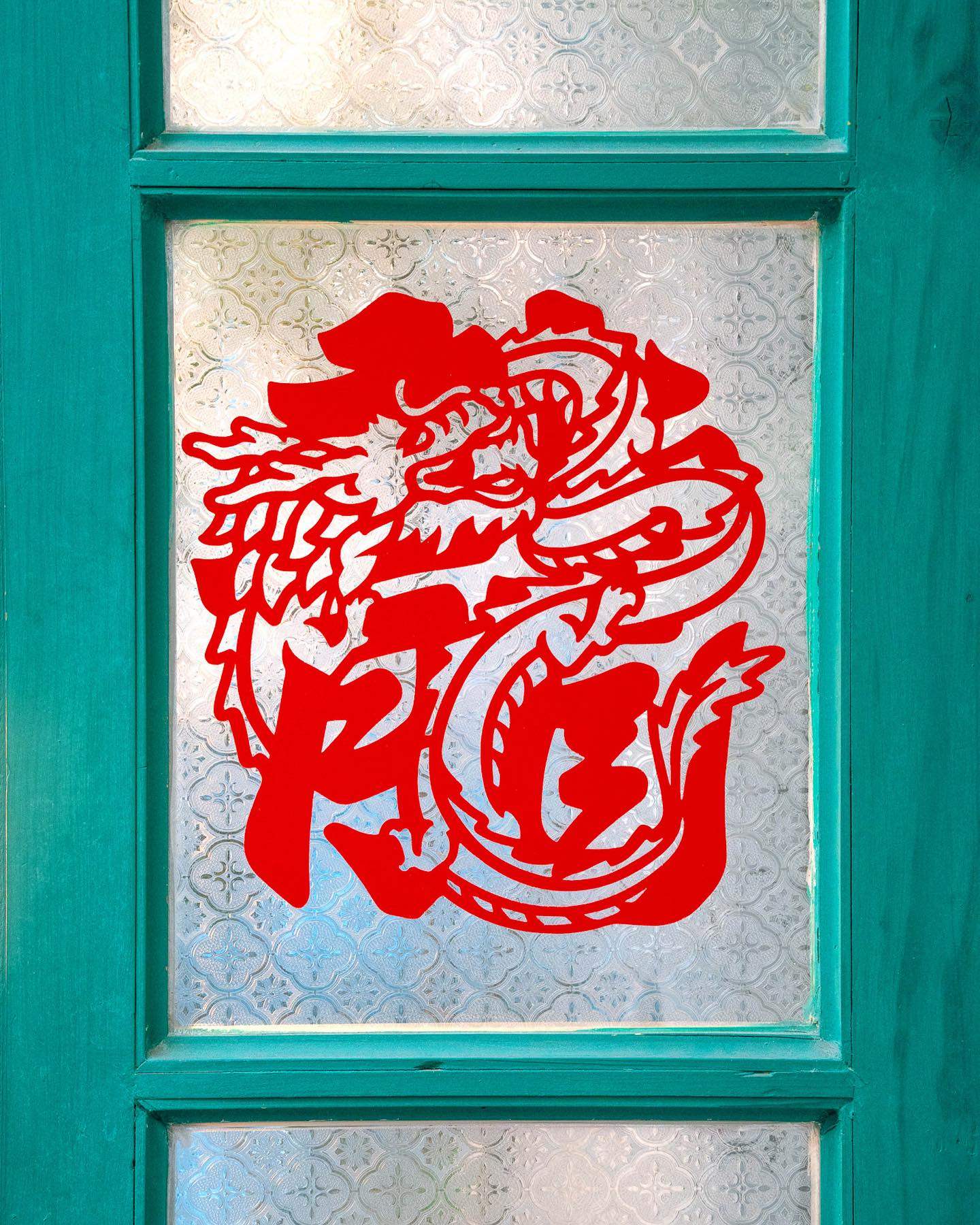

I bought 50 large sheets of red paper – they were just HK$2 (US$0.26) each from an incense shop in Wan Chai. Most people learn to do paper cutting with scissors, but with my model-making experience it seemed more natural to get a cutting mat and use a knife. I drew the outline in pencil and then used a knife to cut through a stack of 16 sheets.

Those New Year paper cuttings helped me make friends It made me realise how much the paper cuttings appeal to people on a cultural levelNick Tsao

It became a tradition that after Christmas, I’d schedule some time to think of a design for the next zodiac animal. My mum’s friends had been giving me Christmas presents and lai see for years, and I enjoyed giving them something back.

A wonderkid in Wuhan

After my master’s, I joined Foster + Partners full time. Because they knew me, and I had retail experience, they gave me an entire shopping centre in Wuhan, China, to start working on.

Cutting up the Big Apple

In 2016, I got the DFA Young Design Talent Award, which funded me to work overseas for a year. The next year, I got a job with landscape architect James Corner Field Operations in New York, he did the city’s High Line.

I arrived in the middle of a cold winter, not knowing many people. The Year of the Dog was approaching, and I’d brought red paper and my cutting knife. I sat in a bar and designed a cutting of a French bulldog. I cut two stacks, so I had 32 cuttings.

Those New Year paper cuttings helped me make friends, especially within the American-Chinese community. It made me realise how much the paper cuttings appeal to people on a cultural level.

Blue-sky thinking

After New York, I returned to Foster + Partners and lived with my mum in Repulse Bay. At Lunar New Year, I made the paper cuttings at home. My mum helped me with packaging and the production took over the whole of the living room, I made such a mess.

In January 2022, I saw on Facebook that someone was moving out of the Blue House [historic tenement building in Wan Chai]. A friend and I decided to pretend to be flat hunting as an excuse to have a look around.

Even though I had no plans to move and the rent for the 600 sq ft (56 square metre) flat was out of my budget, once I’d seen it the idea got lodged in my head.

I talked to my girlfriend, Annie, about it. We’d met six months earlier. On our first pandemic date we went to a gallery in Tsim Sha Tsui and kept our masks on the whole time.

Annie does marketing for a jewellery company and is an Instagram influencer. After two weeks of mulling it over, we moved into the Blue House together.

Making the cut

I didn’t expect the paper cutting to become a business. Each year, it grew bigger until it was hard to do alongside my full-time job. Now, I work three days a week at Herzog & de Meuron and the rest of the time I teach paper cutting and am discovering other business opportunities, like creating souvenirs for corporations.

Every collaboration I work on gives me new ideas.

Hong Kong brand

I used to get called gwei gwei dei (white-ish). I didn’t like that label, the idea that I wasn’t local enough, or I wasn’t international enough. It’s a cultural identity that I and a lot of my international school friends struggled with.

Their hilarious Cantonese culture skits have fans laughing across the world

I’m enjoying contributing to paper cutting from a graphic design side, using my architecture background. Traditionally, in Chinese art, you spend years replicating the masters and only when you are old and have learned enough can you create new things. Western art, meanwhile, is all about creating new things.

I’m doing contemporary paper cutting but trying to speak to a traditional medium.

Hong Kong people have maintained the idea that you need to put up Lunar New Year decorations, but they have become very commercialised. Why does every shop sell the same cutesy dragon? I don’t even recognise them as dragons.

We rely so much on the mainland Chinese market that we don’t have a lot of home-grown decorations, which is the niche I want to fill. A lot of the puns I use – either the text in the paper cutting or the name of it – are in Cantonese and some don’t translate into Mandarin.

I want to design things that are not just Hong Kong-branded but that are culturally specific to Hong Kong.

Nick Tsao’s Lunar New Year paper cuttings are available at The House of Stories, 72A Stone Nullah Lane, Wan Chai. Instagram: @tsaoao.design