Review | From Jay-Z to Virginia Woolf, Zadie Smith’s second non-fiction outing is a mixed bag of essays

British writer muses on everything from the gyrations of Michael Jackson to her car crash of a meeting with J.G. Ballard

Feel Free

by Zadie Smith

Penguin

Zadie Smith is arguably Britain’s hottest literary writer. Her novels, from White Teeth (2000) to Swing Time (2016), have won wide acclaim and she has received nearly every accolade an author can enjoy.

Smith is also an accomplished essayist. A previous collection, Changing My Mind (2009), displayed a talent for non-fiction, and she has followed that up with Feel Free, a selection of her reviews, essays, reflections and more from the years since.

Smith is a sharp commentator on issues related to race. With race relations perhaps less fraught in Britain than in the United States (class arguably being the supreme British social barrier), Smith has been able to capture the experiences and perspectives of a wide variety of characters in her work without offending the sensibilities of Middle England.

Smith notes in her essay on Ballard that she, “born on the outside of it all, was hell-bent on breaking in”. To the cynical, her approach when meeting Ballard may sound like that of someone trying to fit into the literary and broader establishments by echoing their sentiments and donning their manners. Perhaps this is unfair, but faced with an unyielding Ballard, Smith seems innocent of the gleeful malice that writers – think Byron, think Larkin – can exhibit towards other scribes.

A mixed bag, Feel Free is helpfully divided by theme, with sections titled “In The World” (topical issues), “In The Audience” (music, film and television), “In The Gallery” (art), “On The Bookshelf” (book reviews) and “Feel Free” (memoir and reflections).

Readers’ responses might depend on their own interests. Smith cannot quite bring works of art or music to life for someone entirely unfamiliar with them.

“Some Notes on Attunement”, her piece about singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, for example, is a fantastic sociological essay on becoming the sort of person who listens to Mitchell after growing up in a household more devoted to Al Green and Billie Holiday.

Similarly, “The House That Hova Built”, on the genius of rapper Jay-Z, largely concerns his lyrics, background and contemporaries rather than his sound. You don’t come away with a greater appreciation of his voice, rhythms or atmosphere (Smith lauds the “twenty-two delicious plays on the words ‘too’ and ‘two’” in the song 22 Twos, without mentioning what the song sounds like, for instance).

Smith’s pieces are empathetic and understanding: even when she relates how a personal encounter with Ballard went disastrously wrong, she goes on to explore his novel Crash (1973) in a fine essay containing the wonderful line, “Reservoirs are to Ballard what clouds were to Wordsworth.”

While her essays on books, film, dancing and art are certainly discerning, entire parts of the flavour palate seem missing. There is very little sour or bitter on the menu.

But Feel Free can be a little too agreeable. Smith seems to avoid writing about (or at least including here) any creative endeavour she dislikes. This might be linked with her attitude to food: in “Joy”, she writes, “Whatever is put in front of me, foodwise, will usually get a five-star review. You’d think people would like to cook for, or eat with, me – in fact I’m told it’s boring. Where there’s no discernment there can be no awareness of expertise or gratitude for special effort.”

While her essays on books, film, dancing and art are certainly discerning, entire parts of the flavour palate seem missing. There is very little sour or bitter on the menu.

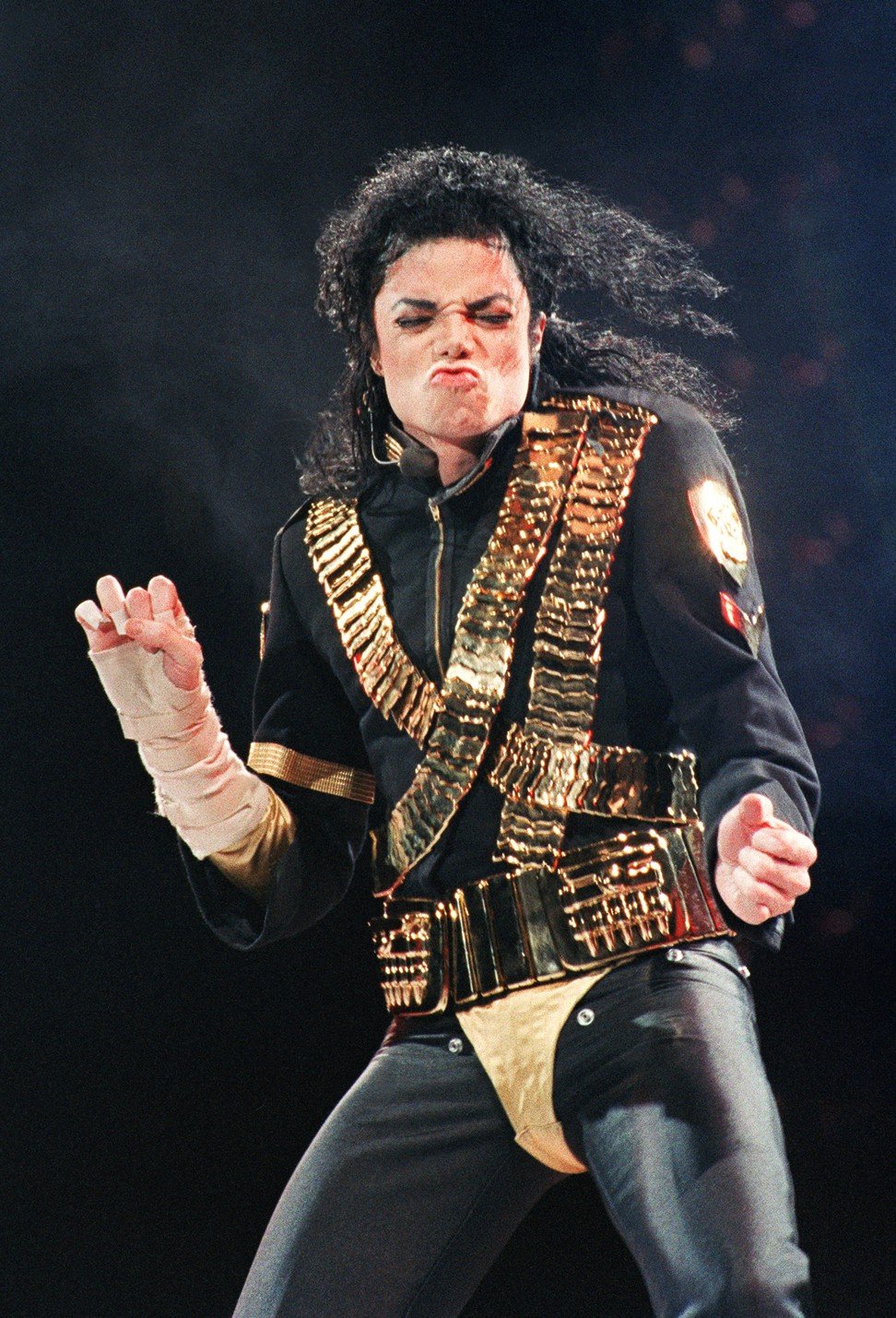

However, numerous subjects spring to vivid life. The simplest and most joyful essay, “Dance Lessons For Writers”, compares and contrasts a series of dancers, from Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to Michael Jackson and Madonna, to styles of writing.

Of the women, Smith writes, “The lesson is quite clear. My body obeys me. My dancers obey me. Now you will obey me [...] Lady writers who inspire similar devotion (in far smaller audiences): Muriel Spark, Joan Didion, Jane Austen. Such writers offer the same qualities (or illusions): total control (over their form) and no freedom (for the reader).”

Similarly, her description of Michael Jackson is spot on: “Every move he made was absolutely legible, public, endlessly copied and copiable, like a meme before the word existed [...] He deliberately outlined and then marked once more the edges around each move, like a cop drawing a chalk line around a body. Stuck his neck forward if he was moving backwards. Cut his trousers short so you could read his ankles. Grabbed his groin so you could better understand its gyrations. Gloved one hand so you might attend to its rhythmic genius, the way it punctuated everything, like an exclamation mark.”

Smith’s writing on politics (in all senses of the word) has mixed results. She has a keen interest in her surroundings and what makes them successful, or otherwise. The micro-level political awareness informs “North-west London Blues”, the first essay from the “In The World” section, where she describes a day in her old manor: London’s Willesden Green.

Smith laments shops that are gone, libraries threatened by closure, the lack of spaces for people to spend time without spending money. There’s an acute sense of her yearning for yesteryear’s certainties rather than a facing up to current challenges. “Fences: A Brexit Diary”, an essay on the aftermath of the British referendum, is likewise well-phrased, neat and intelligent – and feels entirely distant from the nativist rage that shocked the country into the surprise result.

But it’s novels, as Smith concedes, that are her strength. Indeed, in “Some Notes On Attunement”, she admits to being perplexed at how some people can have additional fields of expertise. But this is unduly modest. Her book reviews are wonderful examples of explication and understanding, filled with judicious phrases: school-taught English, for example, is “a cat-o’-nine-tails, to be used, primarily, as a tool for whipping children into submission”.

Smith is without doubt an important British writer, and while this book is not perfect,Feel Free’s range, depth and ambition make it a worthwhile read. And she makes it all feel so nice.