Review | Fire & Blood, Game of Thrones prequel, sees George R.R. Martin stick to winning formula of incest, dragons and destruction

- The latest book from the Game of Thrones creator tracks the Targaryen empire’s intimately entwined family tree

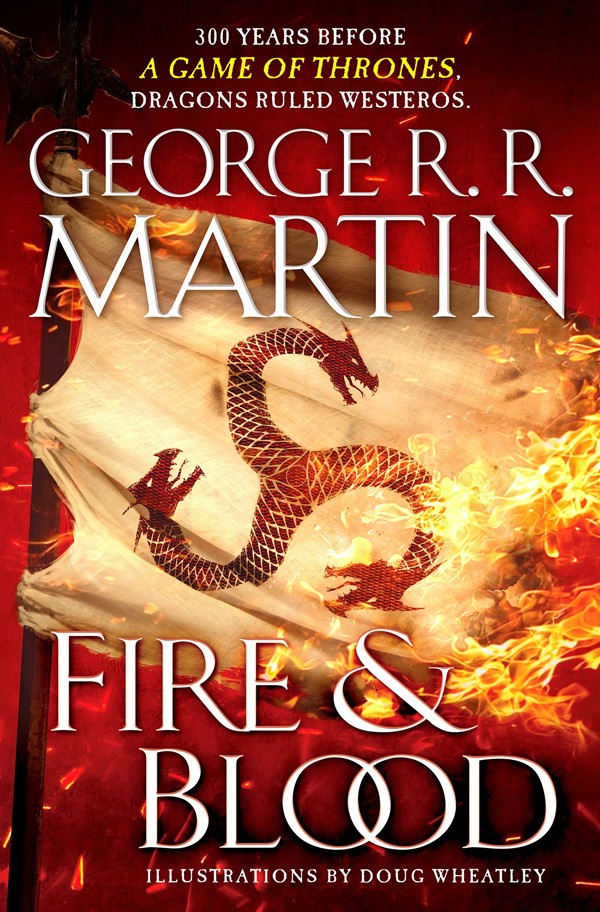

Fire & Blood

by George R.R. Martin

Bantam

There is a character in George R.R. Martin’s new novel named Alys Westhill. This is not her real name: she was born Lady Elissa Farman. Until roughly page 239, Lady Elissa’s claim to fame is as favourite of Rhaena Targaryen, one of roughly 28 million queens roaming Westeros thanks to their husbands’ unfortunate habit of being brutally and bloodily murdered.

Game of Thrones mastermind George RR Martin talks about death, his start in publishing and why writers really write

Rhaena’s other half was Maegor “the Cruel”, who, as his nickname suggests, brutally and bloodily killed her first husband in dragon-to-dragon combat before being himself killed (also brutally and bloodily, as it happens).

Born on a remote and, until Queen Rhaena’s arrival, trivial island, Elissa possesses a powerful relationship to the sea, which eventually supersedes the former queen in her affections. Elissa leaves Rhaena and builds a ship to explore the oceans beyond Westeros. The voyage is financed by three Targaryen dragon eggs that Elissa stole from under Rhaena’s nose – something that later sets the cats among the pigeons.

While Elissa dreams of “other lands and other seas”, her flat-earth followers do not share her enthusiasm: “Then as now, ignorant smallfolk and superstitious sailors clung to the belief that the world was flat and ended somewhere far to the west.”

It is tempting to read these explorations into a world “far larger and far stranger than the maesters imagine” as an allegory of Martin’s all-conquering fantasy-historical series – known to booklovers as Fire & Ice, and to even more people as Game of Thrones. For hardcore Throners, there is no life beyond Westeros, which perhaps explains why Martin is constantly expanding its borders.

Fire & Blood (Martin is presumably too busy to bother typing “and” in full) is the long-awaited prequel to the series. Itis also a stopgap of sorts to the even longer-awaited sixth part of Game of Thrones, A Dream of Spring. (A sidebar: Martin’s forthcoming title quotes Samuel Coleridge’s poem Work Without Hope [as indeed does Groundhog Day], which is not an auspicious omen for those desperate for updates from Westeros.)

Fire & Blood rewinds roughly three centuries before the start of Game of Thrones to describe the creation, establishment and eventual crumbling of the Targaryen empire. To all intents and purposes, this began with Aegon the Conqueror terrorising each of the seven separate regions of Westeros until they fell under Targaryen rule. Aegon’s method was simple, but devastating. He seized power through violence, the implication of violence and canny politicking backed up with violence or its implication, all of which relied on the Targaryen pet. Dragons are the family’s power source, an advantage that separates them from their foes.

As Game of Thrones heads towards final season, George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards to become TV series

The Targaryens don’t just send their enemies to the morgue; they incinerate them with fire-breathing monsters. “The sands around the Hellholt were fused into glass in places, so hot was Balerion’s breath.” Balerion is the biggest and baddest dragon of them all, and whispers of his name are often enough to ensure victory. The Targaryen rulers are by turns smart and stupid, but even the dumbest (Aegon II and Maegor are prime contenders) are 40 per cent better than their rivals when sat atop a vast flying lizard.

This is why Elissa’s alleged theft is so terrifying for Westeros’ then king, Jaehaerys I. Should their primary weapon fall into the wrong hands, the playing field will be levelled. To be fair to Jaehaerys, he might have wits enough to defeat his rivals without recourse to fantasy fiction deus ex machina. For Maegor, by contrast, they are essential: his conception of realpolitik is, essentially, kill everyone who is not me or my mother.

If dragons are the “fire” of the title, then “blood” is explained by the Targaryens’ idiosyncratic take on the notion that “the family that prays together stays together”. A bolder, more candid name for Martin’s book would be Dragons & Incest. While this lacks a certain poetic power and has only niche commercial appeal, it does describe how intermarriage bolsters the Targaryen dynasty.

When Aegon the Conqueror lands in Westeros, he does so with two wives and two sisters. The punchline being that only two women are present: Visenya and Rhaenys. The better wing of the family emerges from Rhaenys and the less successful from Visenya – although with the bloodlines so hopelessly intermixed it’s a miracle they can tie their own shoelaces much less conquer a continent.

All this brother-sister (and just as often brother-sister-sister) action incurs the wrath of Westeros’ religious fundamentalists, and thus incest shapes Targaryen politics as surely as their dragons. While certain holy men look the other way, just as many do not and incite anti-Targaryen sentiment wherever they preach.

Maegor responds in the only way he knows how (dragons, fire, more dragons), but Jaehaerys proves shrewder. While he does marry his sister Alysanne, he does so in private and then seeks to explain this particular Targaryen tradition to the people. He is helped by a malleable Septor, but also by Alysanne, who proves to be the Meghan Markle of her day, joining Jaehaerys on a royal tour of Westeros and winning over everyone she encounters.

‘Game of Thrones’ promises ‘grisly death’ to top donors

Pretty much the same story unravels throughout the 700 pages of the prologue. The Targaryens vie with the Septors, the Lannisters, the Starks, the Hightowers, the Oakenfists, the Manderlys and, of course, other Targaryens. Hardcore Throners will doubtless thrill to the extended creation myths about the Kingsguard, the Hand and The Wall (with the occasional Wildling thrown in). I confess my head spun rather as Aegon married Rhaenys, who gave birth to Rhaena, who married Aegon (II), who gave birth to Aerea and Rhaella and possibly Paella. Before long I couldn’t tell my Aerea from my Aelbow.

It is to Martin’s credit that despite being frequently up to my neck in all these Targaryens, I rarely lost interest. Fire & Blood skips along in a fair imitation of an old-school but populist work of history. The narrative is low on dialogue, save when an older source is being cited. These vary from traditional chronicles, to the comical sounding The Testimony of Mushroom, to Westeros’ own version of Fanny Hill or 50 Shades of Grey: a notorious account of a young noblewoman’s sexual deeds.

What these sources provide is motivation to go with Martin’s primary interest in action. Here perhaps is Fire & Blood’s more serious intent: to illustrate what a strange beast history can be. Often the only ways to understand the strange and distant past are strange and distant texts, beliefs and, well why not, dragons.

Winter is coming - again! ‘Game of Thrones’ prequel is on the way

Martin’s narrator is constantly butting in to interrogate the story he is telling. For example, why does Jaehaerys remain silent about his marriage to Alysanne? “Was he repenting a match made in haste? [...] Had Alysanne somehow offended him? Had he grown fearful of the realm’s response to the marriage?”

The response to all these alternative histories sounds sure-footed: “Arguments have been made for all these explanations,” he writes, adding: “To this writer it seems plain that Jaehaerys was not repenting his marriage and had no intention of undoing it.” Yet how is that knowledge “plain”, exactly, putting aside for the moment the important fact that the narrator is George R.R. Martin and he has invented the entire universe?

For all the brave deeds, fierce battles and impressively progressive women, the hero of Fire & Blood isn’t a Targaryen but epistemological uncertainty. This may not sound sexy, unless perhaps mumbled by Kit Harington, but it does ring bells in our own age of “fake news”.

If you are struggling to know what exactly is going on, never fear: no one in Westeros did either, including George R.R. Martin.