Review | Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’ novel Legends of the Condor Heroes Book Two is out in English, and it’s thrilling

- ‘Jin Yong’ has entranced generations of Asian readers, and with this latest release Western audiences can discover why he was so revered in Asia

- His novel takes up the story of Guo Jing, 13th century kung fu fighting hero, his equally adept lover, Lotus and their never-ending battles

A Bond Undone: Legends of the Condor Heroes Book Two

by Jin Yong (translated by Gigi Chang),

MacLehose Press

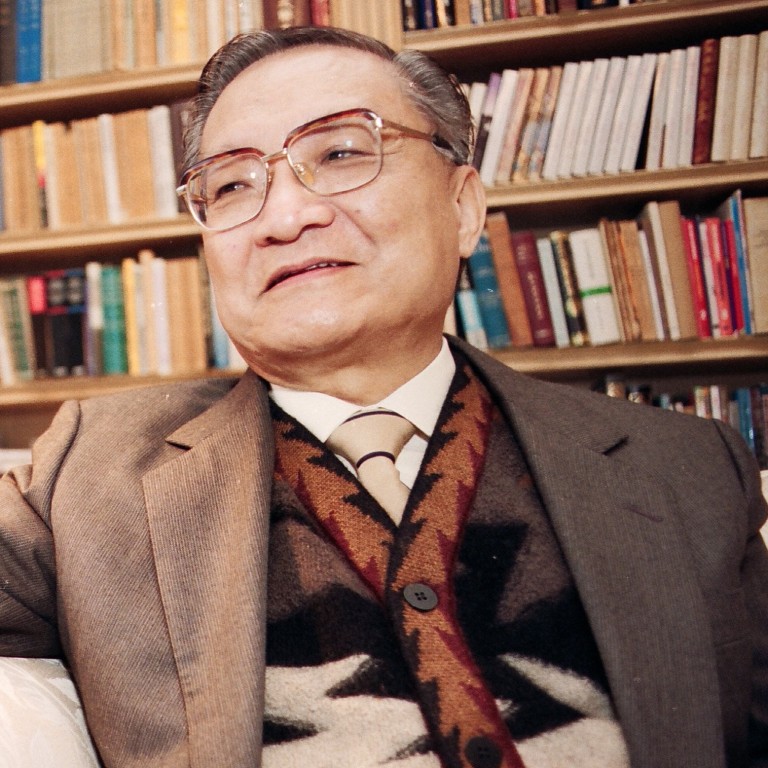

The death in Hong Kong last year of Louis Cha Leung-yung – known to his readers as Jin Yong – ended one of the great literary careers of modern times. Too popular, perhaps, to be seriously considered for a Nobel prize (despite former Chinese president Jiang Zemin sending ambassadors to plead the author’s case), Jin Yong’s wuxia novels sold by the hundreds of millions, and spawned an entertainment industry all of their own – generating sequels, spin-offs, movies, video games and graphic novels.

The life and legacy of Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’

Jin Yong’s status outside Asia, however, is less stellar. Obituaries in the Western media outlets that covered his death seemed required to refer to him as “China’s J.R.R. Tolkien”. While this short cut gave a sense of Jin Yong’s vast sales and epic stories, it was also necessary to explain a writer who was little known in anglophone literary circles.

His novels can routinely be read in Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese, but there is a dearth of English-language editions: before 2018, only The Book and the Sword (1955) and The Deer and the Cauldron (1969) had been released, and that was almost two decades ago.

The project was launched in February 2018 with A Hero Born. “You hold in your hands the first volume of one of the world’s best-loved stories and one of its grandest epics,” Holmwood wrote in the short introduction. “And yet this is the first time it has been published in English, despite making its appearance in a Hong Kong newspaper over half a century ago.” Now, just a year later, MacLehose has released book two, A Bond Undone, translated by Gigi Chang, who has rendered classical Chinese dramas into English for Britain’s Royal Shakespeare Company.

Reboots, updates and translations of beloved works are laden with joys and pitfalls, and Holmwood’s translation of A Hero Born is no exception. An appendix addresses the “controversy” surrounding the title: should the Chinese character diao be translated as “eagle” or “condor”? Rather more inflammatory was the decision to rename Jin Yong’s beloved heroine Huang Rong as Lotus Huang.

Whether the variations were great or small, A Hero Born still narrates the early years of Guo Jing, who was born amid in the political tumult of 13th-century China. Guo’s father having been killed by invading Jin forces, his mother flees to Mongolia, where she is protected, if that is the word, by Genghis Khan.

Six of the best-known characters from the world of martial arts novelist Jin Yong

For Jin Yong, the constant factional strife is largely a backdrop for the thrilling foreground of Guo’s bildungsroman: essentially, a solid, decent, if not exceptional young man transforms into a hero after learning kung fu from a group of eccentric sifus (the Seven Heroes of the South).

Guo’s progress through adolescence intersects with that of Lotus, a brilliant, mercurial, sprightly, petulant imp of a girl, raised by the fearsome outcast kung fu master (Apothecary Huang) on Peach Blossom Island. The other leading man is Wanyan Kang, son of Wanyan Honglie, the Sixth Prince of the Jin Empire. Attractive, if you like wealthy, powerful, entitled princes, Wanyan Kang collides with Guo after the Duel for a Maiden – the maiden being Mercy Mu, who turns our trio into an unstable love quartet.

A Hero Born ends with so many cliffhangers it’s a miracle the book didn’t topple over and plummet into the sea. At the end of a finely choreographed mass brawl, Guo and Lotus combat a bewildering host of adversaries (Old Liang, Tiger Peng, Hector Sha) while the reader combats an equally bewildering series of revelations.

Spoiler alert … Wanyan Honglie’s consort (real name Charity Bo) comes face to face with her supposedly dead husband, Ironheart Yang, and together they confront their spoiled, brilliant and clueless son – drum roll – Wanyan Kang.

These battles and exposés hang heavy over the start of A Bond Undone, which has hardly begun before we witness acts of noble self-sacrifice, a resumption of hostilities and a semi-supernatural whirling dervish named Cyclone Mei, who whirls despite being paralysed from the waist down.

A word of warning for Jin Yong novices: Condor action moves with quicksilver speed, and nowhere quicker than in the mind-bending fight scenes, which are narrated through delectable moves that lose little in translation: “black tiger steals the heart”, “luminous hollow fist” and “dragon-subduing palm”, among many, many others.

In one bout between Lotus and her hopelessly smitten aggressor, Gallant Ouyang, she rises to her opponent’s challenge, outwitting him through a cheeky surrender, is on the verge of being cut to shreds by three razor-sharp cymbals, flies between these weapons towards a monk adopting the “deadliest kung fu [pose], the five finger blade”, only to reveal another trick she has kept quite literally up her sleeve. All this in just over two pages.

What proves both exquisite and refreshing in Jin Yong’s battles are not only moments of humour, but their grace. Combat is developed not through the crunch of bone (as in Western thrillers by, say, Lee Child), but an elegant to and fro of motion and counter-motion

A confession: it didn’t take this reader long to fall head over heels for Lotus, the mischievous heroine who giggles as she fights, delights in toying with opponents both more experienced and stronger than herself, is headstrong and impetuous yet independent and tenderly in love with Guo. My adoration peaked during a concluding contest between Guo, now schooled in kung fu by the towering gourmand sifu Count Seven, and the viper prince, Gallant. The place is Lotus’ home, Peach Blossom Island; the judge is Lotus’ tetchy, fearsome kung fu heretic of a father, Apothecary Huang; the prize is Lotus’ hand in marriage, which she would sooner cut off than give to Gallant.

“If you don’t want to get married, I don’t mind at all,” Apothecary says softly at one point, in an appeal that sends Lotus over the edge.

“‘You don’t love me! You don’t love me!’ she cries, stamping her foot. Count Seven was shaking with laughter. Apothecary Huang – the martial great who dominated the lakes and the seas, the murderous monster who killed without remorse – had been gagged and bound by his young daughter’s tantrum.”

What proves both exquisite and refreshing in Jin Yong’s battles are not only these moments of humour, but their grace. Combat is developed not through the crunch of bone (as in Western thrillers by, say, Lee Child), but an elegant to and fro of motion and counter-motion. Kung fu is driven by cause and effect, technique and emotion, feints and surprises – just like Jin Yong’s narrative. Intelligence and sensitivity to one’s surroundings outweigh brute strength.

This, in part, is why A Bond Undone is so seductive a read. Even the most action-packed passages appeal directly to the imagination. The fact that so many of the moves seem to defy all probability (Guo “[bobbing] serenely on a branch”, or what exactly a move called “the haughty dragon repents” entails) is precisely their point and lends them their literary force.

I translated Chinese writer Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’. Here’s why he never caught on in the West

Jin Yong’s kung fu really is a martial art, something that is made explicit when Guo watches a peerless fight between sifus Count Seven Hong and Viper Ouyang: “Guo Jing was mesmerised by the innovative and the unexpected in each move. He could not have imagined such kung fu, even in his wildest dreams.”

Brilliant, exciting, romantic and often very funny, the English-language “Legend of the Condor Heroes” has been well worth the wait, which only makes the wait for part three both an exquisite pleasure and unbearable pain.