Review | City on Fire revisits Hong Kong’s 2019 protests and asks ‘what next’?

- Lawyer Antony Dapiran gives voice to both sides in what publisher describes as an essential guide to ‘fight for the very soul of the city’

- He also explores a long history of dissent, including the 1967 riots and the 2014 ‘umbrella movement’

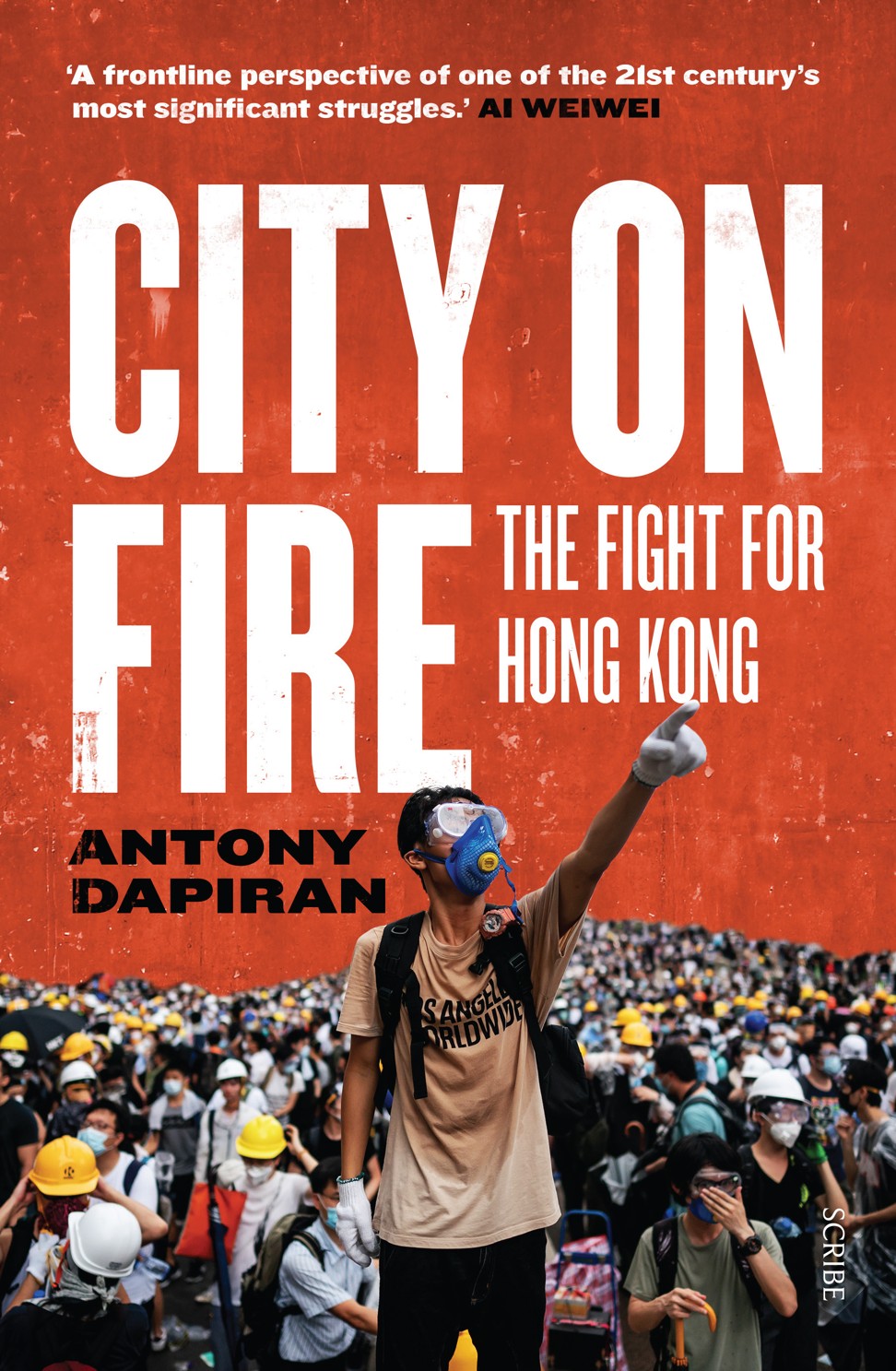

City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong, by Antony Dapiran, Scribe, 4.5/5 stars

City on Fire lives up to its publisher’s promise of providing an essential guide to the Hong Kong protests. Its author – writer, lawyer and long-term Hong Kong resident Antony Dapiran – is renowned as a clear-eyed observer of the city’s politics. His 109-page book, City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong (2017), was lauded for its incisive analysis of the “umbrella movement” and the emotions that propelled it.

But City on Fire is more than a mere extension of this history of dissent. It illuminates every phase, trigger and turning point, skirmish and tactic in what began as a protest against an extradition bill but became “a fight for the very soul of the city”.

“And what,” he asks late in the book, “is the soul of a place, but its identity?”

The prologue sets the tone and haunts the ensuing 20 chapters. Devoted entirely to a study of tear gas, it would be tempting to skip it – given its use in Hong Kong has been widely covered – were it not for its urgent, almost poetic potency. At the end of the prologue, Dapiran writes: “Hongkongers have a new saying, a new aspect to their identity: ‘You’re not a real Hongkonger if you haven’t tasted tear gas.’”

Beginning with a description of the “graceful arc” of tear gas canisters as they drop “down out of the blue sky”, Dapiran discusses everything from its properties and effects, both physical and psychological, to its historical origins and uses.

Dapiran opens the door to an extraordinary tale of identity and tear gas, violence and enchantment, creativity and desperation, and how they manifested on the streets of Hong Kong and coalesced into a new-found solidarity. He also asks why the Hong Kong police deployed so much tear gas “often when the crowd was not violent nor charging police lines”.

Later, when Dapiran describes the final destruction of trust between the Hong Kong police and the public – marked by the storming of the Prince Edward subway station, in August – many may wonder whether this could have been avoided had the police read Winchester’s words. Or if the government had heeded initial calls for an independent police inquiry. Or whether this perilous rift was the desired outcome all along.

As international experts would later note, police tactics largely contributed to this breakdown, Dapiran writes. He probes this rift and the “near impossible” position in which the police were placed by a “vacuum of governance”, in a compelling chapter titled “The End of Summer”.

“Hong Kong in 2019 became a city on fire, and this was the spark,” writes Dapiran, who goes on to examine every aspect of the extradition bill, the government’s reasoning for it and the public opposition.

Dapiran gives voice not only to Lam and various pro-Beijing politicians, supporters and police, but also to those on the pro-democracy side including tycoons, politicians, protesters, academics, artists and ordinary Hongkongers. People such as 27-year-old social worker Rachel, who tells him how she feels about Glory to Hong Kong, the stirring song adopted by protesters as Hong Kong’s de facto national anthem. “When the police beat our students, I feel very helpless. But when I sing this song, I feel very powerful,” she says.

A Mandarin-speaking lawyer, who has spent 20 years advising Chinese companies, many of which are state-owned, on raising money and listing on the Hong Kong stock exchange, Dapiran is forthright about his stake in the issue, along with that of others in the legal profession. “We depended for our identity as Hong Kong legal practitioners upon the fact that under One Country, Two Systems, Hong Kong retained its own legal systems and courts, separate and distinct from that on the [Chinese] mainland.”

Dapiran’s informed take on Hong Kong’s legal and electoral systems, and the threats to its “one country, two systems” model, is a potent feature of his book, as is his capacity to convey Hong Kong’s spirit and the genius of its youthful protesters. His considered analysis of the future of that system and “the slow and steady squeeze” he believes Beijing will now exert on Hong Kong makes essential if sobering reading.

Dapiran transports the reader deftly into the slipstream of Hong Kong’s long history of dissent: the 1967 riots and the 2014 “umbrella movement”, which he also witnessed, are recurring historical touchstones. He travels into the city’s public spaces and narrow, congested streets, its malls and MTR stations, where he too chokes on tear gas as he seeks to understand the mindset and “be water” tactics of the youthful protesters.

Inspired by Bruce Lee, the “be water” strategy has energised activists around the world, even as the protests in Hong Kong have eased. But it would be a mistake to think the city’s unrest has ended, Dapiran writes. He outlines Hong Kong’s crucial role as a safety valve for sentiment that has no other outlet in Xi Jinping’s China.

In 2003, he reminds us, it was Hong Kong that collected and disseminated information on the Sars outbreak, saving China, if not the world, from a possibly devastating epidemic. But will China keep that valve open? The answer, Dapiran writes, “will determine whether 2019 will also be remembered as the last year of Hong Kong as it once was”.