Dress Codes: law professor Richard Thompson Ford presents a history of why we wear what we wear

- Snubbed for the title of Esquire magazine’s Best Dressed Real Man in America, legal academic Richard Thompson Ford responded with a look at fashion history

- He explores what we wear and how that has evolved in tandem with political control and social change

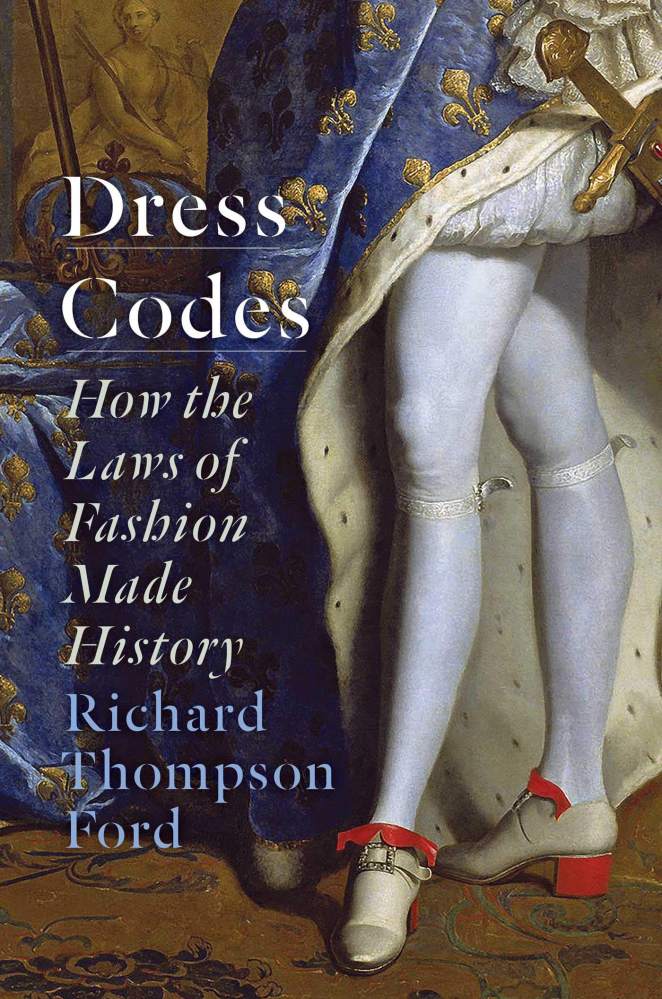

Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History

by Richard Thompson Ford

Simon & Schuster

In 1565, an English servant called Richard Walweyn was arrested for wearing a pair of “very monsterous and outraygeous” hose. In those days, hose were equivalent to trousers; they covered up, but also emphasised, male behinds. Judging by portraits, the ideal was to look as if you were wearing a pair of giant pumpkins. The court, however, ordered that Walweyn’s offending garments be confiscated and put on public display as an example of “extreme” folly.

Several centuries later, in 2009, an American legal academic called Richard Thompson Ford decided to enter Esquire magazine’s Best Dressed Real Man contest. His wife, Marlene, took a photograph of him in a favourite blue pinstripe suit with their 10-month-old daughter, Ella, wriggling on his lap. When Esquire rang to interview him about his personal style, Ford was down to the last 10. Afterwards, he was told he hadn’t made it to the final five. He was crushed; although he explained the law for a living, he felt he’d failed to define the significance of why he wore what he did.

He has now combined both interests in a book.

Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History is a forensic examination of what we wear and how that has evolved in tandem with political control and social change. The unfortunate Richard Walweyn kicks off proceedings. The point is that Walweyn’s fashion crime wasn’t the cut of his hose; it was that he was a servant. As Ford writes, “He’d disrupted the political order of a society that treated outward appearance as a marker of rank and privilege.”

His literary wardrobe, therefore, is stuffed with corsets, armour, bloomers, veils, zoot suits, black turtlenecks, tuxedos and hoodies, and the people who wear them range from saints (Joan of Arc) to kings (both Louis XIV and Martin Luther) to nuns (in habits inspired by Christian Dior) to prostitutes (who, depending on when and where they lived, were forced to dress in either the gaudiest or shabbiest attire).

Ford draws a direct line between Londoner John Hetherington, who was accused of inciting a riot in 1797 for appearing in public wearing a silk hat – “a tall structure having a shining lustre and calculated to frighten timid people,” according to The Times – and New York’s Straw Hat riots of September 1922. September 15 was known as Felt Hat Day, when the season (and hats) changed; for eight days that year, gangs had attacked men who thought otherwise.

“Making it a global project is something I considered but, honestly, just understanding the relationship between fashion and culture would be much more difficult,” he says, via Zoom from Stanford University, where he’s a professor at the Law School. For the record, Ford, who is 54, is wearing a casual loose-necked blue jumper. (It’s California, on a Friday evening, in lockdown.)

The book is studded with gleams of his own sartorial diktats. In a section about blazers – originally red, hence the name – he takes the opportunity to include a mini thesis on buttons. (Then there is the question of placement.) He admits to a partiality for the Neapolitan shoulder and the surgeon’s cuff. When Atlanta’s Morehouse College is criticised for introducing a dress code in 2009, Ford’s issue is with critics who don’t understand the function of cufflinks (… they attach to shirt cuffs, not jackets).

Morehouse was founded for black men and Ford, who is black, is at his most engaged when tussling with the legal history of African-American fashion. Like Elizabethan England, laws in 18th century America forbade slaves from dressing “above their condition”. The black population was expected to dress in humble attire; during World War I, when black soldiers returned to Mississippi, white mobs threatened to strip off their uniforms. Half a century later, as Ford writes, “respectable appearance was a mandatory part” of the 1960s civil rights era. When they marched, protesters wore their Sunday best.

The book is dedicated to his father, Richard Donald Ford, who was born in Alabama, trained as a tailor and eventually became the first black dean at California State University Fresno. Perhaps the most piercing sentence in its 440 pages reads: “Though he was on friendly terms with every janitor in the building, he could not afford to be mistaken for one.” For his father, Ford writes, a jacket and tie “even in the often-withering heat” were both protection and an assertion of status. Asia may not feature much in the book but for many of its immigrant families that paternal mindset is a truth, universally acknowledged.

For the Netflix generation, learning about the West’s restrictions adds a certain pleasure to the faux Austen colour-blind sumptuousness of the Bridgerton era. By happy coincidence, the book includes a portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle, born in 1761, who was the black grandniece of Lord Mansfield, chief justice of England and Wales, and moved in the highest realms of society.

Corsets, long gloves: how Bridgerton sparked a new fashion trend

There are plenty of who-knew moments among the legal niceties: boys used to be dressed in pink! Christian Louboutin’s red-soled shoes echo the scarlet heels of height-challenged Louis XIV! Army officers carried make-up into battle! Ford has written more academic works, but with this topic he says he’s had “a blast”. He has even inserted that other fashionable Ford – Tom – into a paragraph about Daniel Craig as James Bond.

Ford Snr died in 1997 so he never knew that the son he tutored in his dress code was judged Esquire’s sixth Best Dressed Real Man of 2009. What does his own son, Cole, 17, wear? Ford laughs, ruefully. It turns out that forensic analysis of costume five centuries ago is easier than studying today’s trends at home.

“Right now, he dresses like his peers and they wear T-shirts and sweatpants every day. They don’t do what I and my friends did in high school, which is to have trends and striking little tribes – you know, the Preps, the Punks, the Mods.” The Plastics … “Right! They’ve got a different aesthetic going on that I’m not sure I entirely get.”