The upcycling, zero waste firm eliminating waste from the design world

- Taipei-based Miniwiz’s portable, solar-powered reprocessing machines take consumer waste and turns it into construction tiles

- It is one of a number of the firm’s showcase design projects that highlight what recovered waste materials can really do

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure, as the old saying goes. It is something Arthur Huang has truly taken to heart.

The gregarious 41-year-old CEO of Taiwanese firm Miniwiz is on a mission to make zero waste the new standard in design and construction. And he has a library of 1,200 objects made from cigarette butts, plastic bottles, old clothes and other discarded materials to show for it.

“The challenge before was there was no material data for post-consumer waste,” says Huang, who founded Miniwiz in 2005. Nobody knew exactly what could be done with different kinds of objects and few people were able to trace the impact of turning something old into something new. Now that Huang has 14 years of data from his company’s own work, he says the numbers speak for themselves.

Based on a life-cycle analysis of Miniwiz’s projects, the carbon footprint of using recycled materials is always much lower than using new materials – “often 90 per cent lower”, Huang says.

Last year was particularly fruitful for the Taipei-based company, which employs 100 people. It unveiled the House of Trash, a 4,300 square foot (400 square metre) flat in the Italian city of Milan fully outfitted with recycled materials and upcycled objects.

Later in the year, several large, sail-like inflatable canopies designed by the firm were the centrepiece of a reopened 23.5 kilometre (14.6 mile) cycling track looping around Bangkok airport. The canopies were made entirely of plastic bottles collected from the airport, though looking at them you would never have guessed it. The track, known locally as the Skylane (official name: the Happy and Healthy Bike Lane) was reopened by the Thai king himself, Rama X.

Huang says projects like these are meant to spark interest in the substance behind their style.

“These are our ‘mission impossible’ projects,” he says. They are meant to defy expectations of what recovered waste materials can do – and how they look. These are not shabby-chic designs, Huang says, unlike so many hodgepodge upcycled products.

The House of Trash is a good example. At a glance, it is a punchily decorated bourgeois flat in the centre of Milan. But all of the furniture is made of products that were once destined for the landfill.

Much of the space is stocked with Airtool furniture from Pentatonic, a Berlin-based start-up similar to Miniwiz, including a chair made from 96 plastic bottles and 28 aluminium cans, and a table made from 1,436 cans and 190 DVDs. The glassware is fashioned out of used smartphone glass, while Italian architect Cesare Leonardi contributed his own furniture made from recycled parts.

The canopies at the Bangkok bike park highlight an evolving approach in the way Miniwiz presents its creations. For example, its nine-storey EcoArk pavilion from 2010 – the world’s first large-scale building fashioned from recycled plastic – deliberately referenced the building’s origins by making visible the remnants of the 1.5 million bottles used to make every brick in the structure. That the bike-park canopies are made from recycled materials is far less obvious, a sign of the company’s growing engineering prowess.

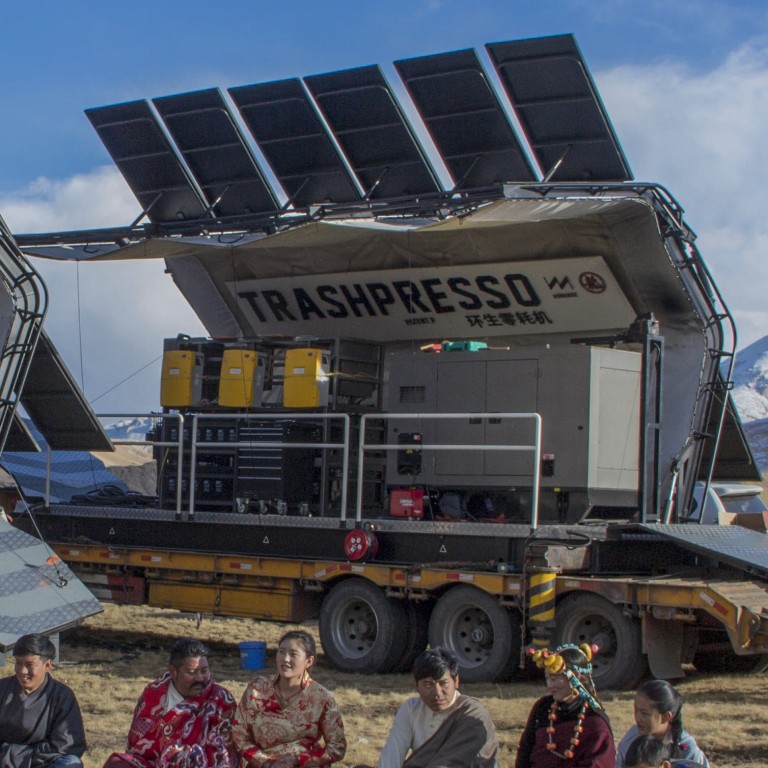

Miniwiz’s current project is its most ambitious yet. Currently, the company sources its materials from third-party recyclers. But Huang says the process is inefficient and inequitable, since the “pickers” at the bottom of the recycling chain earn pennies for each object they collect, which are then resold for a much higher price. In 2017, the company introduced Trashpresso, a portable, solar-powered reprocessing machine that takes consumer waste and turns it into construction tiles. Not only does it cut out the middlemen of the recycling business, it generates no waste of its own.

“The goal is zero secondary pollution,” says Huang, who launched the system in China’s remote Qinghai province, hoping the area’s spectacular natural setting would emphasise the system’s lack of environmental impact.

This year the company hopes to take Trashpresso a step further by launching a closed-loop recycling system in Singapore. Consumer waste will be collected and processed by “mini-Trashpresso” systems that will transform it into building materials. Huang describes it as “hijacking” materials directly from consumers.

If it becomes the standard way of doing things, it will be a new currency for doing good. Otherwise you just end up with more c**p on the earth, in the sea, in the air. We need a liver to clean our blood

He says Singapore was an obvious choice because it is a relatively small city, with an educated population and a government and private sector that are both keen on innovative ideas.

“It’s the lowest hanging fruit,” he says. If the project is a success in Singapore, it can be rolled out in more challenging cities – perhaps even Hong Kong, which at the moment sends the vast majority of its waste to landfills.

For all of his showcase design projects, Huang is most excited about the potential of this new system to eliminate waste from the world of design.

“If it becomes the standard way of doing things, it will be a new currency for doing good,” he says. “Otherwise you just end up with more c**p on the earth, in the sea, in the air. We need a liver to clean our blood.”