How architecture can affect emotions: Hong Kong’s first crematorium for ‘abortuses’ uses design to ease pain

- Architecture masters including Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier influenced BREADstudio’s choices in designing the Home of Forever Love in Kwai Chung

- Whether they recognise how the space affects their emotions, parents feel ‘respect … of the life that they had lost’, one of the architects says

For sale: baby shoes

Never worn

That unsettling six-word story appears like a news ticker in my mind’s eye the moment we arrive at Kwai Chung’s Home of Forever Love (HoFL), Hong Kong’s first crematorium for “abortuses” of less than 24 weeks’ gestation.

I’m here to understand how architecture can affect the emotions and why even the smallest details matter.

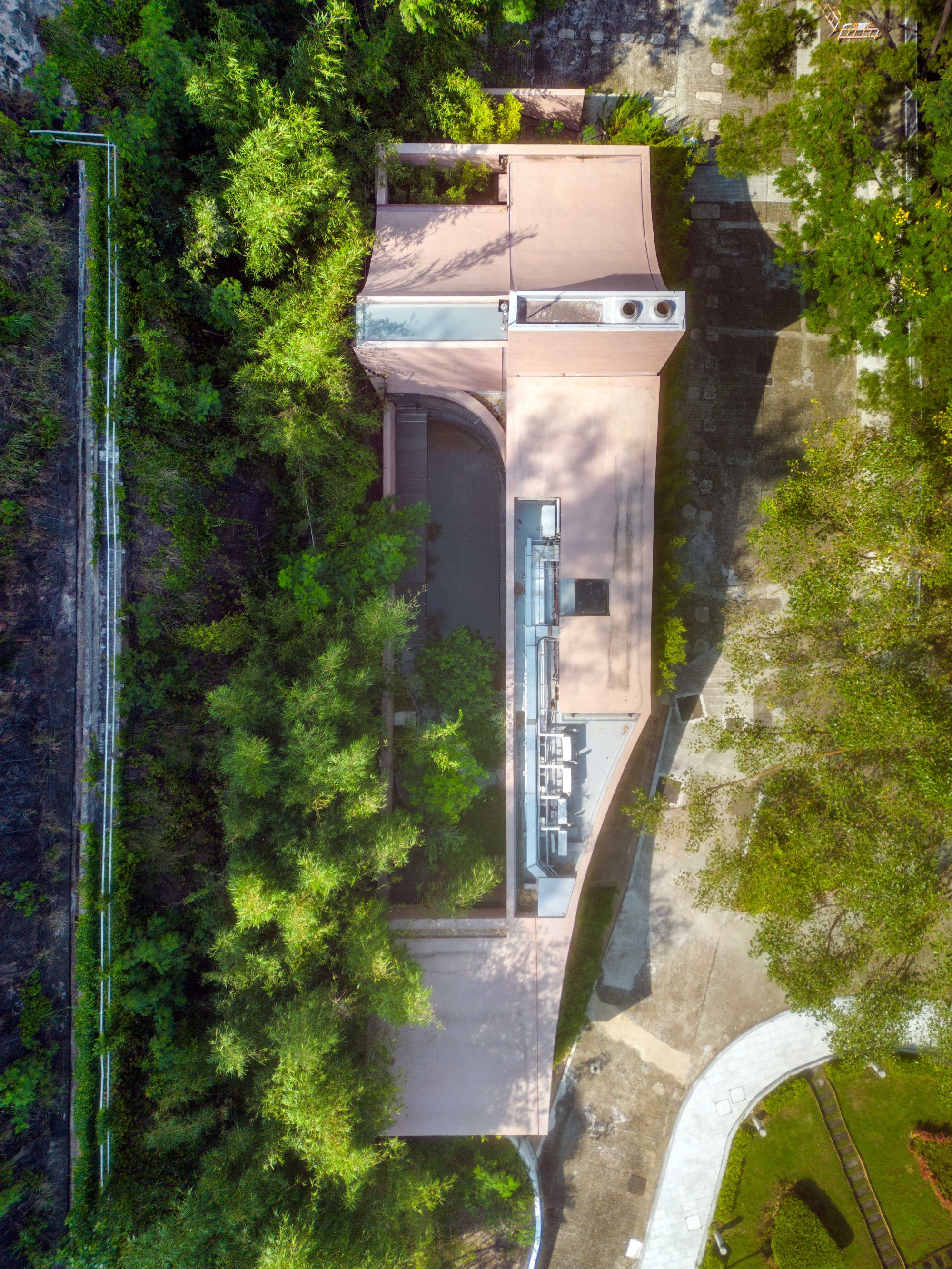

Just inside the entrance portal, a semi-enclosed courtyard beckons. Visitors circumnavigate the leafy plot partly on paving stones that curve around a crepe myrtle feature tree – believed in some cultures to invoke divine blessings. Loose white pebbles complete the circle.

Over this pale, cobbled bed, ashes of the unborn are scattered at the conclusion of a choreographed journey around the one-year-old complex that ends where it begins, or starts where it stops – by design.

In the year to August 31, 2023, 491 aborted fetuses were cremated at HoFL, of which 84 were through family-organised private services at the site.

How 3D printing is helping resurrect a century-old village in rural China

The rest were “unclaimed”, from public and private hospitals and healthcare facilities in Hong Kong, according to the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD), which manages the facility.

That this is not a place one visits for enjoyment is a given. But Paul Mui Kui-chuen of BREADstudio hopes the experience can be burnished by time.

From a design perspective, HoFL leaves an indelible impression, although my first lesson is a reminder of best-laid plans. Shortly before our meeting on site, uphill from Kwai Chung Crematorium, a message arrives from BREADstudio’s other co-founder, Benny Lee Chiu-ming, saying: “I’m sorry I cannot attend as my pregnant wife just went into labour.”

Just as well neither of us is superstitious.

But loss links us all, which is why BREADstudio designed the 2,070 sq ft (192 square metre) monolithic concrete structure for all faiths (or none), although the perceptive might spot a discreet, off-centre cross formed from the horizontal and vertical axes of the window frame in the farewell hall.

The room is otherwise free of religious symbols, its focus being a small stone altar that extends from an arched wall opening with similarly shaped timber doors.

Partly because of their diminutive proportions and the dusty-pink surrounding walls, there is a fairy-tale-like innocence about the fixtures. The many curves – everywhere you look – enhance visual comfort.

During ceremonies in this 10-person, 100 sq ft room, the baby’s remains rest on the altar in a white cardboard container the size of a shoebox. When it is time to say goodbye, or even goodnight, the box is pushed beyond the outer wooden doors into an inner chamber.

Flip a switch and the cubicle turns dark. “It’s like putting them to sleep when you turn off the light and close the bedroom door,” Mui says.

That is the cue for staff on the other side of the wall to take charge.

Via Zoom several weeks later, Lee, by now a father, reveals that the two cremators at HoFL are the first of their kind in Hong Kong. Taking a year to arrive from Germany, the machines are “more delicate and much smaller” than comparable furnaces for adults.

Just as well HoFL’s ambient light soothes, filtered by bamboo and other flora visible through the building’s ample glazing. And from the narrow skylight at the top of the room’s tall swooping roof, celestial beams descend, hitting the altar in the morning and afternoon.

“We engineered this to convey ascension,” Lee says. Rays of light can be seen as a bridge between the earthly and ethereal.

According to the FEHD, two-hour bookings of HoFL are the norm. Although visitors can leave at any time, many complete the linear, unidirectional circuit on the same day or during a return trip (eliminating the one-hour wait for the ashes).

From the hall a path beside the serene reflecting pool – a feature commonly found at memorials – leads back to the main courtyard.

While emphasising that HoFL was designed to serve a need in the community, not as BREADstudio’s pièce de résistance, Lee acknowledges that works by a handful of architecture masters influenced their choices.

Lessons about circulation, and the sequence and hierarchy of space, came from Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion. From the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, designed by Louis Kahn, the pair learned about water’s optimum flow rate, among other things.

Careful calibration to prevent stagnation generated “just enough falling-water sound and ripple”, Lee says.

He and Mui also gleaned much about spiritual and spatial quality from the architecture of Carlo Scarpa and Enric Miralles, whose Igualada Cemetery in Catalonia has been described as one of the most poetic 20th century works of Catalan architecture.

The use of concrete for HoFL was partly influenced by that masterpiece and Scarpa’s contemplative Brion Tomb funeral complex in Italy.

“The crematorium will in the long run become more earthy,” says Lee, adding that their material and colour selections diverge from the default stark tiles government projects usually demand for ease of maintenance.

Le Corbusier’s influence, abstractly reproduced in HoFL’s emblem, is also palpable. The portal beneath which visitors enter was born of the Swiss-French architect’s convent at La Tourette, France.

There, visitors are ushered through a burly, free-standing concrete gateway that an online architecture enthusiast describes as marking “the border between the realm of nature and the realm of man”.

It is an “architectural trick”, Lee says. The portal affords a sense of arrival in new worlds. To the left is a “kiosk” for digital services, portending the future of funerals; in the middle is the courtyard; to the right is the main building, where the roof swooshes to its highest point (9.3 metres) to accommodate a chimney.

By comparison, the portal, at 2.5 metres high, is relatively squat. “We intentionally squeezed the entrance to as low as possible,” says Mui, expanding on a different reason for effecting spatial tension and release.

“Parents are very upset when they come here, so normally they keep their heads down,” he says, mimicking stooped movement. “This fits that heavy mind, heavy emotion.”

But as they make their way towards the open, lofty spaces, he hopes the feeling of reaching new dimensions brings with it a shift in mood.

All that said, such design strategies are simply that: techniques to assuage pain that may or may not be lost in translation, especially during the fog of grief.

Lee acknowledges as much, recounting an encounter at HoFL in 2022 with a group of parents who had lost their offspring. Their reaction to the facility reflects the power of empathy.

“Whether or not they understood the architectural space, or how spatial quality affects the emotions,” he says, “what they felt was the respect and the acknowledgement of the life that they had lost.”