A Rohingya refugee documents decades of horrors as a member of Myanmar’s persecuted ethnic minority

First, They Erased Our Name author Habiburahman was a carefree child when his grandmother told him of the campaigns of violence and terror against his people. Two generations later, little has changed for the stateless Rohingya

He goes by a single name. But Habiburahman, better known as Habib, can lay claim to two identities, and at least nine lives. And for most of his 40 years on this Earth he has been stateless – even since 2010, when he was granted refugee status in Australia, where he now lives and works in construction in Melbourne.

But you won’t find him complaining about the eight years he has clocked up waiting for an Australian protection visa.

The desperate plight of those displaced by the most recent spate of military violence has been well documented, less so the preceding decades’ continued campaign of ethnic cleansing.

“There have been many media reports about the Rohingya since 2017, when more than 600,000 suddenly turned up at the Bangladeshi border,” says Habib in his fractured English, one of several languages and dialects he speaks. “But 30 or 40 years ago, we had Rohingya people living in 17 townships across Arakan [Rakhine] state. Now you will find only eight or nine.”

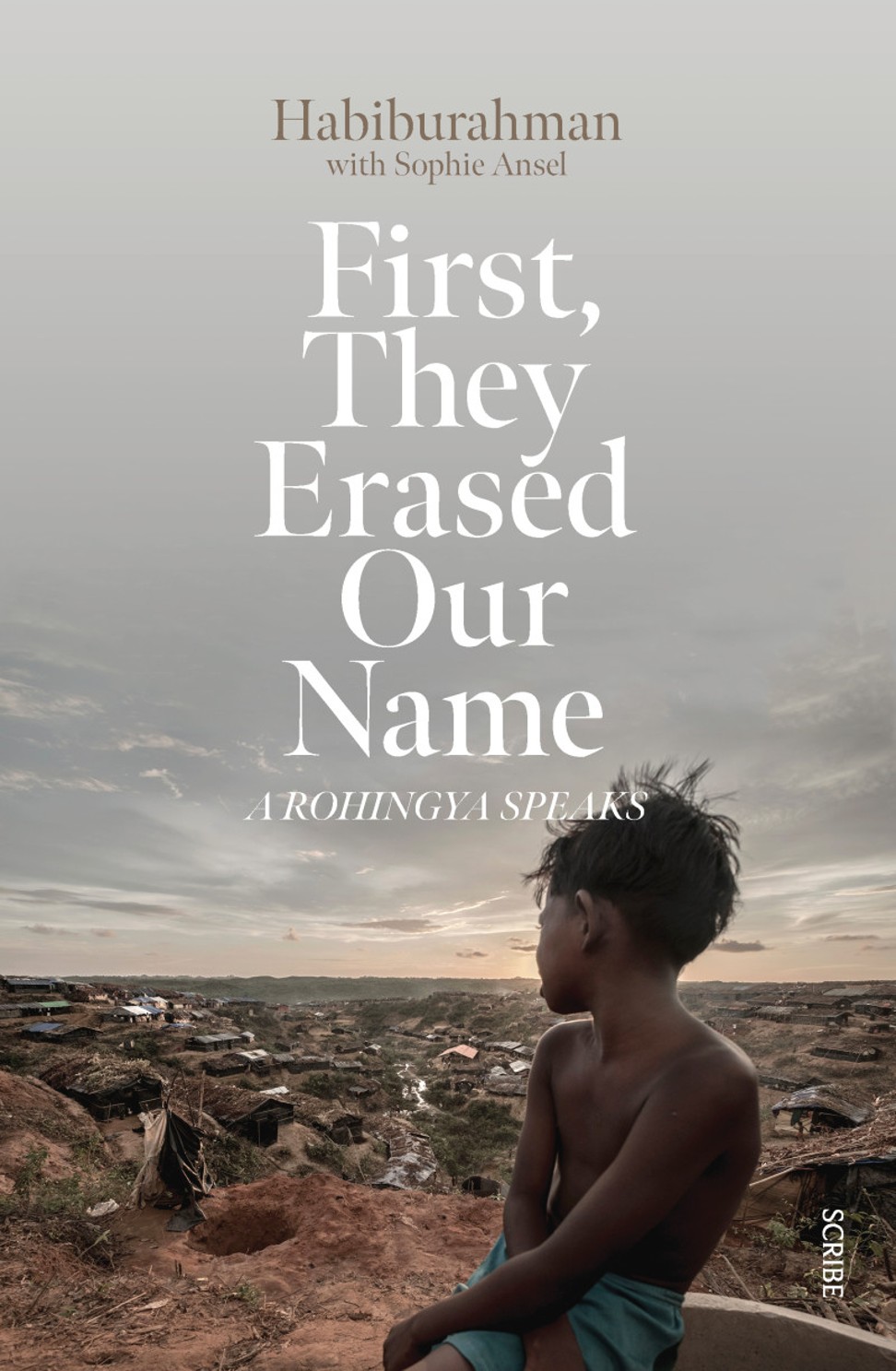

Published this month and translated by Andrea Reece, First, They Erased Our Name (Scribe) was conceived in 2006 after Habib met French journalist Sophie Ansel in Malaysia, during the nine years he lived there illegally. He and Ansel wrote his memoir via email exchanges, while he was detained in Australia from 2009 to 2014, and into 2017.

“Rohingya people are being removed from their land at an amazing pace,” says Habib. “This upsets me very much. I wanted to put it in writing, and I found the right person to help me.”

Habib’s story begins in 1982, when he was a toddler, and Ne Win, the military general who, in 1962, dismantled Burma’s parliamentary democracy and established a dictatorship, brought into force the country’s infamous Citizenship Law. From that moment on, to retain Burmese citizenship, it became essential to belong to one of the 135 recognised ethnic groups that form part of eight “national races”.

The Rohingya were not among them.

“With the stroke of a pen, our ethnic group officially disappears,” Habib writes in his memoir. “From now on the word ‘Rohingya’ is prohibited. It no longer exists. We no longer exist. I am three years old and am effectively erased.

“That law not only excluded us from being citizens, but also doesn’t allow us to apply for citizenship, because they say Rohingya have no proof of existence prior to the 1823 British occupation. That’s why the word ‘Rohingya’ is forbidden, because if they use that word, the history will clearly say that Rohingya existed in Burma before then.”

If that sounds arbitrary, it is. Ne Win was notorious for seeking advice from astrologers and soothsayers, and while previous constitutional provisions incrementally downgraded the Rohingya’s social status, this was as unfathomable a move as the colonial cut-off point was contentious.

Habib grew up in Mylmin, a mountain village in Rakhine. Sheltered in the embrace of his loving family, he was oblivious to their extreme poverty, but aware of the ethnic pecking order from a very young age. There were “the animist Khumis, followed by a large number of Christian Matus and Zomis, some Buddhist Bamars and Rakhines, who are closely associated with the governing powers, and some 20 or so Muslim families, in other words, us, the Rohingya”, he writes. “But we keep that quiet.”

At home his family spoke Arakanese, and in the wooden shack that served as the village school he spoke Burmese. There, his Khumi friends affectionately called him “the Muslim”, but the children from the Bamar and Rakhine groups refused to call him, or his family, anything other than kalar – a derogatory term denoting disgust for dark-skinned ethnic groups, which he likens to the N-word. Habib writes, “I hate it when they shout this name, as if they were spitting in our faces. I do my best to ignore them.”

Grandma brings with her ‘endlessly tedious’ tales of rapes, massacres, imprisonments and fleeing through dark forests. Fleeing, endlessly roaming, shrieking and screaming for help

It was only when his grandmother arrived to live with them that he learned the Rohingya dialect, as it was what she used to speak in private to Habib’s father.

“Grandma brings with her ‘endlessly tedious’ tales of rapes, massacres, imprisonments and fleeing through dark forests. Fleeing, endlessly roaming, shrieking and screaming for help. The ghosts of our family and our people who perished, decapitated by swords or burnt to death,” he writes.

That is when she wasn’t giving her grandchildren household tasks, such as milking the goats, feeding the hens or collecting firewood. Or herself climbing the slope back up from the Kaladan River, weighed down by two water buckets hanging from either side of a wooden pole balanced on her shoulders. Even at night by the fire, she sang lullabies about Operation Nagamin, or Dragon King, the massive cleansing campaign in 1978, which sent grandma fleeing through the forest from her home village to seek shelter in Mylmin. She also constantly spoke of the 1969 “cleansing” campaign in which her father was arrested and her son (Habib’s father) was forced to flee from Arakan to Chin state.

Her “never-ending stories”, writes Habib, “are always followed by a moral lesson and prayers to God, a burdensome chore she drums into us on a daily basis when all my brother Babuli and I want to do is play”.

Play, Habib’s father told him at age seven, “is a luxury that we cannot allow ourselves. You must know your place. You have to be more responsible than children from other groups”. But Habib and his friend Froo Win, a Christian animist child of Khumi and Rakhine ancestry, loved nothing more than to play in the forest, despite his father forbidding entry to the military “black zone”.

Habib was nine years old when, in 1988, villagers of all colours, religions and ethnic groups marched arm in arm through the streets of Mylmin chanting, “Highlanders! Freedom!” The protests that erupted throughout the country that year, resulting in Ne Win’s resignation and the installation of a military government known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), are, like so many of the historical events that bleed into Habib’s memoir, never explained.

For Habib and his friends, the marches were an opportunity to weave joyously through the protesters playing a game of tag. A few days later, soldiers emerged from the forest, the river, the surrounding plains, and laid siege to their village. “For the first time I witness neighbours, men and women alike, being dragged away from their families and taken I don’t know where. I never see them again,” he writes.

What nine-year-old can understand why his parents go missing in the middle of the night and return battered and bruised? What child can grasp the significance of their mother telling their father in a broken voice, “the president of the SLORC had a baton that he kept thrusting into me”?

As soldiers poured into his mountain region in ever greater numbers, ostensibly rounding up rebels from the Chin ethnic minority, Habib’s little world became one of anguish. By the time he reached his teens, Operation Pyi Thaya, or Clean and Beautiful Nation – one of more than nine such operations between 1969 and 1991 – had been running for a year and stories of massacres and deportations of Rohingya in Mrauk-U, the ancient capital of Arakan, as well as nearby villages, reached them throughout the 1990s. As he writes, “I often wish I could stop time and remain the carefree child who is vanishing past with each passing month.”

Habib’s voice sounds a bit far-off, and not just because we are on the phone between Perth and Melbourne.

“I used to play and run with friends, but slowly, year by year, I came to realise the distinction between us and other people,” he says. It was “the most difficult and painful of all aspects of [writing] my story, because I had to recall all my family, and in recalling all these memories I began to feel much worse on behalf of my parents and grandmum.

“I felt doubly bad remembering all those stories my grandmum told me, because when I was listening to them, I thought they were boring. But when I looked back at the reports on the overall displacement of people, the number that had been killed and the number of villages destroyed during those times, and operations like Dragon King, that’s when I realised why my grandmother could not forget, and how it must have affected her”.

Habib was already in Australia by the time he learned of his grandmother’s death, and how she had returned to her Arakan village just before the arrival of the military in Mylmin, then fled through Bangladesh into Saudi Arabia, where she died.

“I’m not sure exactly when I heard, or why or when she passed away,” he says, “but it was about eight or nine years ago. Many memories came flooding back then.”

Habib believes he was 14 or 15 when the military commandeered his family’s Mylmin home to use as regimental latrines.

Leaving the confines of one’s home village was a crime for Rohingya, and remains so today, but thanks to Habib’s father’s friendship with the local Christian priest, the family were able to pay off the military, the police and the immigration authority, and be allowed to leave Mylmin for Sittwe, the former British capital of the once independent Arakan state, a two-day journey by longboat via the region’s labyrinthine river system.

It was the only place where they had family, who, like most Muslims, had been relocated from their old neighbourhoods to new, curfewed, Rohingya “settler communities” on the outskirts of towns and cities. It was the only place they could legally live, and “if you do ever leave Arakan”, explains Habib, “you can never go back alive”.

Here he trained himself not to react to the never-ending taunts of “filthy kalar”, the frequent beatings and daily humiliations and extortions, be it by military, police, monks or the Nasaka, the feared special forces who patrolled the streets enforcing the segregation of kalars from the rest of the community.

“There are no Chins, Khumis or other minorities here,” writes Habib. “The kind of diversity that encourages tolerance does not exist.”

He learned never to protest the forced labour most Rohingya are called upon to do, describing his approach as “something like a chicken heart. Whenever we are in this kind of confrontation, we do nothing, just tolerate whatever they say, do whatever they ask, and be ready to pay them”.

Habib came to realise he inhabited the land of grandma’s tales, surrounded by the terrors she had described to him as a child. Now here he was, having come full circle, no better off than her, two generations later.

One day, he saw Froo Win, feet chained to those of a dozen other emaciated prisoners, breaking stones. In exchange for precious food, the guard gave Habib five minutes to speak with his old friend, who had been arrested in Mylmin at age 15 and transferred to Sittwe to do hard labour. To this day Habib doesn’t know what happened to Froo Win.

Habib arranged, after many false starts, to be smuggled onto a cargo vessel going to Yangon. Only after he arrived in the capital did he inform his father.

To “do first, tell afterwards is followed in most Rohingya families”, he says. “If, say, the authorities arrest me, they will arrest, detain and torture my parents and all of the community. So this was a huge risk, but it was something I really prepared for. I was already at risk in Rakhine, so I felt I had no choice but to take another risk to get out of there.”

In Yangon, the 18-year-old Habib managed the unthinkable for a Rohingya – he got accepted into college by lying about his ethnicity and home state, and, of course, by paying lots of money. This he earned, along with rudimentary accommodation, by working as a hostel cleaner. At the college he was taken under the wing of a kindly Burmese teacher, who enlisted Habib and other ethnically diverse classmates in a secret project: to distribute pamphlets containing an inventory of Myanmar’s natural resources, to raise awareness about this wealth being stolen from the people by the military junta. The project soon landed him and many of his classmates in jail, where they were subjected to several days of torture and interrogation.

“I never thought I would escape from there, or that I would even survive the beating,” he says. “My only thinking was to not put my family in danger, and to accept whatever came to me.”

After a week, their teacher visited the jail, paid off the guards, called each student by name and urged them to jump out of the window and run in the direction he told them to. He directed Nyi Nyi, aka Habib, to the hostel, where he later gave him money and clothes, and told him to leave the country. His escape route would take him through the remotest parts of Shan State, controlled by the Wa rebel army, who assisted him across the border into Thailand.

Habib has no regrets about the brutal end to his dream of an education forbidden by his birthright because, he says, his teacher gave him a taste of what a united Myanmar could be like.

“The schoolteacher, everyone, called me ‘son’, they were very polite. I was never called kalar. In my life, I never had this, except at home. It was totally different,” he says. “People in those areas, they don’t know how badly the Muslim, the Rohingya community, is being treated […] Most people in central Burma have never even been to Arakan.”

Habib managed to flee to Thailand in 2000 but was arrested by Malaysian police on a bridge in the Thai border town of Golok that same year, then transferred to a military camp in Kelantan. Ten days after that he and some 80 Burmese prisoners thwarted an attempt to deport them by parting with all their money and possessions, including belts and shoes, to instead be handed over to traffickers.

His father had put him in touch with a friend who loaned Habib money to pay the traffickers. The friend had borrowed the funds from a marble contractor and Habib had to work off the debt with seven months unpaid labour.

Subsequent stints in detention camps followed, and when free, Habib laboured on construction sites. He also worked on an illegal fishing trawler in the Andaman Sea – at gunpoint. By 2009, Habib was on his way to becoming the Rohingya spokesman he now is when he heard news of his father’s death, succumbing to torture during his 12th time in prison.

“My father died not knowing exactly where I was, and what I had been doing for Rohingya people in Malaysia,” he says.

In Kuala Lumpur, Habib had begun protesting outside embassies and writing press releases for a Rohingya association. He also acted as a fixer for the 2009 Channel 4 documentary, Refugees for Sale, which embarrassed the Malaysian government by revealing how corrupt officials were selling refugees to gangsters in Thailand. A month later, with his arrest imminent, Habib boarded a small, unseaworthy escape vessel to Australia’s Christmas Island. Inevitably sinking, the vessel was, miraculously, rescued by the Australian Navy.

Habib has a sister who is now in Norway and another trying to claim asylum in Australia, but he still feels he failed them in his duty as the eldest son, when he couldn’t help them during the 2012 Rakhine violence that displaced them.

“I was not able to do anything to help them, and they didn’t know that I was in detention,” he says. “If I had let them know somehow, it [would have been] a risk for them. Also there is no phone, no internet in western Burma. Not like [Australia].”

Yet despite having lived “in a cage” for so long, Habib bears no animosity, just a great sadness and a need to tell the world what is happening to his people in his homeland, and that it has been happening since the 1940s.

We cannot attack the public, because the Burmese public are innocent. The majority of people don’t know that 300 to 400 Rohingya villages have been destroyed, and the new generation of Burmese today are even saying there is no Rohingya, because they have never heard of them

“The Burmese government want to build a completely Buddhist state,” Habib says. “So to wipe out the Rohingya they are using Rakhine people. Sometimes they use Rakhine, sometimes they use majority Burmese, so that when the international community come to talk about this, they can say, ‘Oh no, not us, this must be Rakhines or some other group.’ This is the technique of dividing people that the Burmese government has been using for years.

“We cannot attack the public, because the Burmese public are innocent. The majority of people don’t know that 300 to 400 Rohingya villages have been destroyed, and the new generation of Burmese today are even saying there is no Rohingya, because they have never heard of them. And even if you tell them there is an ongoing war in Kachin or Shan State, let alone what is happening in Rakhine, they will not accept this, because it’s not happening to them. The best thing is to educate them. That’s why I wanted this book to be written in a plain, matter-of-fact way. Because even though so much of my story is painful, there is no benefit in hatred or anger.”