- Hong Kong’s museum of visual culture has opened in a city much changed. Whether it can fulfil its global ambitions and satisfy Beijing remains to be seen

With M+, the timing is always off. After years of complaints that the museum of visual culture was taking too long to build, it is opening at long last – smack in the middle of a pandemic. A coterie of international VIPs would otherwise have flown into Hong Kong for the November 11 unveiling of the first Asian institution of its kind, but not when they have to spend up to 21 days in hotel quarantine.

A more consequential misalignment may have to do with last year’s introduction of the national security law in Hong Kong and an increasingly nationalistic model of governance in the special administrative region of China.

M+, described as a global museum for art, design, architecture and the moving image, was originally meant to open in 2017. The years of delay might be seen, in hindsight, as a historic opportunity squandered – a lost chance for a world-class museum to operate in a city that remained one of Asia’s freest, most open and most cosmopolitan for years after its return to Communist China. In those precious years, the museum could perhaps have begun to establish itself as a truly regional voice unhindered by nationalistic considerations.

That’s the pessimistic view.

As this striking, megalithic harbourfront monument opens its doors, it still aspires to be the lodestar of Hong Kong’s ambitions as an international cultural hub. Whether it will succeed will ultimately boil down to the same old question that has dogged it since the day it was proposed, by a government-appointed consultative committee in 2007: does it properly represent Hong Kong? And which Hong Kong does it represent?

Suhanya Raffel, M+ director since 2016, is celebrating the opening as, for better or worse, a uniquely Hong Kong moment.

We bedded down all the opening exhibitions in 2018 and have not changed the selections sinceSuhanya Raffel, director, M+

“Nobody outside can come to the opening but it is an opportunity as well,” she says. “This is an institution for this city. We can really engage with the city now, because we are all here and not travelling. After all this time, after all this waiting, it is very nice to make the museum opening about Hong Kong.”

But the context is very different from 1996, when the West Kowloon Cultural District, to which M+ belongs, was first suggested by the city’s Tourist Association. In recent years, the focus of Hong Kong’s cultural policy has shifted away from maintaining freedom of expression to defining a society which is now first and foremost “grounded in Chinese traditions”.

Those critics went through the museum’s online catalogue and demanded that it hide, or even get rid of, works such as Ai’s Study of Perspective – Tian’anmen (1997), a photograph of the artist raising his middle finger against the backdrop of the Gate of Heavenly Peace in the heart of Beijing. (M+ has taken down the image from its website.) In March, Eunice Yung Hoi-yan, a barrister and a pro-Beijing lawmaker, said in the Legislative Council, and in subsequent interviews, that the work “incited hatred against the nation” and therefore could be breaking the national security law.

Collector Uli Sigg, she claimed, could also be guilty, since it was the Swiss businessman who gave the work to the museum, along with more than 1,500 other pieces of contemporary Chinese art. The campaign against M+ also targeted other works in the Sigg Collection for offences such as insulting Chinese Communist Party heroes or containing nudity or references to sex and religious symbols causing “indecency” and “moral harm”.

In 2012, Sigg chose Hong Kong as the permanent home for his collection because the city’s “one country, two systems” governance model enshrined freedom of expression.

In 2016, some of the highlights from the Sigg Collection were shown in Hong Kong for the first time, at ArtisTree in Taikoo Place. There was barely any political reaction at the time, even though the exhibition, curated by Pi Li, the Sigg Senior Curator at M+, did not shy away from sensitive subjects.

But now that the museum is opening, the Sigg Galleries’ contents will be seen as the benchmark for how much freedom M+ still has. Given the burden of being a major test case for Hong Kong, the contents of these specific galleries remained a closely guarded secret before the opening. When the doors finally opened to the media on November 11, it was revealed that there are not just one but two works by Ai on display.

There is the video Chang’an Boulevard (2004), and there is Whitewash (1995-2000), 126 Neolithic clay jars unearthed in China that are arranged in rows on the ground, with some coated in white paint by the artist. It is not a direct provocation like Study of Perspective, but it is still an irreverent treatment of ancient artefacts, and could therefore be seen as a critical comment on Chinese history and identity.

“We bedded down all the opening exhibitions in 2018 and have not changed the selections since,” says Raffel, emphasising that there has been no censorship or other political interference.

So it was a pleasant surprise to find that the overall impression from the galleries that we were given early access to – such as the Hong Kong visual culture and the design and architecture sections, and an exhibition called “The Dream of the Museum” (see below) – is not one of timid circumspection, but of playful and irreverent exuberance.

There is an eye-catching splash of bright red on a wall in the exhibition tracing Hong Kong’s visual culture since the 1960s. It looks like Mao Zedong’s “little red book”, but is in fact a 1997 Hong Kong advertising awards yearbook.

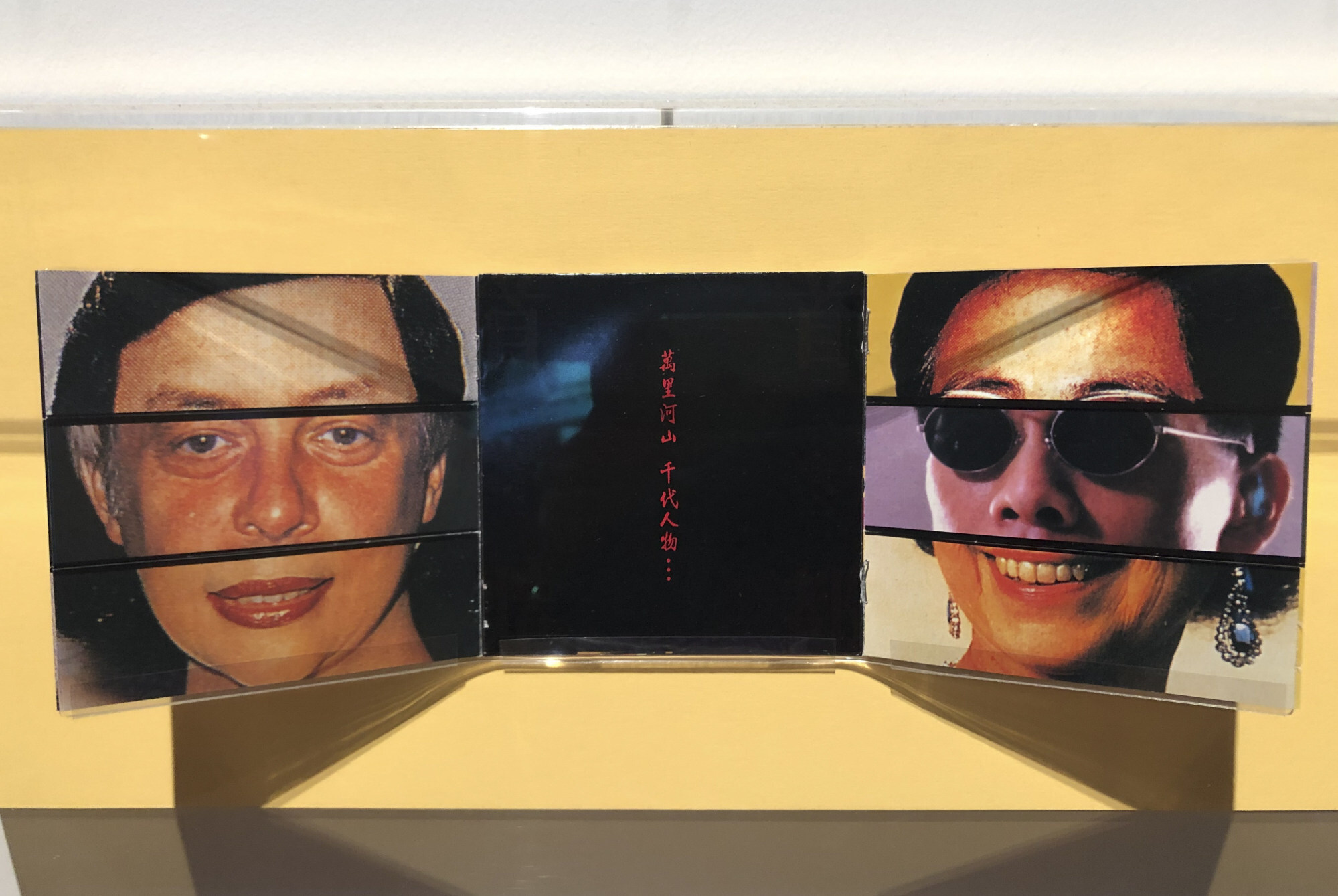

Also on show is Alan Chan’s design for singer Lo Ta-yu’s 1992 CD insert, which has folding panels that allow people to mix and match images of Deng Xiaoping, Mikhail Gorbachev, Queen Elizabeth II and Martin Lee Chu-ming. In the design and architecture galleries, an entire room is blocked off and fashioned into a futuristic spaceship fitted with screens showing Cao Fei’s “RMB City” series – a fictional Chinese city constructed in a virtual world.

The dramatic, churchlike Focus Gallery contains just one work: an arresting crucifix made up of digital screens that South Korean artist duo Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries prepared especially for the venue. Phrases in written Cantonese, such as “Ho Yeh”, meaning hurrah, and in English (“Oh Yeah!”) flash through the video displays with a semi-human chorus blaring out from speakers.

Another sign that the museum is holding its nerve is the forthcoming book Chinese Art Since 1970: The M+ Sigg Collection, edited by Pi. In it, Philip Tinari, director and CEO of the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, has written a scholarly piece on Wang Xingwei’s New Beijing (2001) that does not shy away from the direct references to the 1989 Tiananmen Square square crackdown, and also provides historical context and visual analysis of the painting.

Beijing art centre UCCA ready to feed Shanghai’s appetite for culture

Raffel seems remarkably calm in the immediate lead-up to the November 11 official opening ceremony, despite last-minute setbacks such as leaking roofs and late changes in gallery set-ups demanded by the fire department.

The Sri Lanka-born Australian came armed with formidable and unusually diverse experience – she spent years working in Greek and Roman antiquities in London, ran the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, built the Asian collection at the Queensland Art Gallery and was deputy director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, in Sydney, all before landing the gig in Hong Kong.

Her predecessor Lars Nittve, who came from the Tate Modern in London, is credited with putting down a solid foundation for the museum that included getting Sigg to part with his Chinese collection, working with the architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron to plan the building, as well as laying down the all-important governance structure that gave M+ a high level of autonomy from the government. (It is not a widely known fact that M Plus Collections Limited was incorporated in 2016 to serve as trustee of the museum collection. It, rather than the museum, owns the legal interest in the collection on behalf of the Hong Kong public, and is an additional buffer between the collection and “inappropriate de-accession”: selling or giving away an object from the collection, according to the original Legco papers.)

But there was plenty left for Raffel to do, including planning for the conservation and storage facilities, less glamorous but just as vital as other parts of the museum. “It has been a productive and intense relationship to refine the plans with the architects,” she says.

That is likely an understatement. When the West Kowloon Cultural District was first proposed, cynics were quick to say it was probably just another property development project in a city that was very good at building the “hardware” but lacked the “software” to fill galleries, theatres and concert halls.

With M+, the opposite seems to be true. The collection of about 7,000 artworks and 46,000 archival objects, gradually introduced to the public via a series of exhibitions at a temporary pavilion since 2016, has set a consistent tone for what the museum aims to be – a place where art, design, architecture and moving images are seen from an Asian perspective and informed by global trends.

That has not happened. Chief curator and deputy director Doryun Chong and Lesley Ma, curator of ink art, have been at M+ for eight years; Pauline J. Yao, lead curator, visual art, and Pi, for nine years; Tina Pang Yee-wan, curator of Hong Kong visual culture, for seven years; Ikko Yokoyama, curator of design and architecture, for five years. And one of the most respected members of the team, lead curator of learning and interpretation, Stella Fong Wing-yan, for 10 years.

We always take a historical distance – a distance that allows for objectivityDoryun Chong, deputy director and chief curator of M+

By comparison, the construction work has been an unmitigated nightmare. First, the architects had to find a way round a section of the MTR tunnel that sits just 1.5 metres below ground level directly under the museum site. They put in a basement level around it, with the tunnel segment jutting out as a concrete platform – now called “Found Space” – on which Chen Zhen’s Round Table – Side by Side (1997) is placed.

Nobody seems to know how much the cavernous structure in which concrete features heavily is going to cost, except that it will certainly be more than the original HK$5.9 billion budget, as the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority (WKCDA) has warned.

And there are parallels with another Herzog & de Meuron project – the Elbphilharmonie, in Hamburg, Germany. The concert hall took about 10 years to build and was 10 times over budget, as detailed in the documentary The Elbphilharmonie – Hamburg’s New Landmark, which was screened in Hong Kong earlier this year.

After watching it, I asked Edman Choy, an associate at the Herzog & de Meuron office in Hong Kong, what he thought, and his view was, as with all imaginative, architectural landmarks, details about the budgets and delays will all be forgotten given time.

At the moment, Hong Kong taxpayers are footing the bills, paying millions in interest to businesses owed money from WKCDA’s Blue Poles Limited, the subsidiary that took over Hsin Chong’s role in 2018, as several subcontractors have confirmed. (The name, Blue Poles, is the same as the title of a Jackson Pollock painting that caused a huge outcry in Australia when the National Gallery paid A$1.3 million for it in 1973. Today, it is considered a Pollock masterpiece and the original price tag has been more than vindicated.)

Raffel remains adamant that there is sufficient accountability for the construction process. “I last went to Legco in September and have been regularly updating,” she says. “I don’t think any museum director in the world does that. There is governance in place, overseen by our finance and budget subcommittee.”

Back in 2013, the soft-spoken expert in modern and contemporary Asian art Doryun Chong left the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and “when I told people I was going to Hong Kong, people would say, why would you do that?” he says. “I was confused by their reaction. I had certain fantasies about the city. I grew up in Korea in the 1980s, when Hong Kong cinemas were in their golden age. Korea was still coming out of a repressive period. To me, coming initially from a monolinguistic culture, Hong Kong is culturally diverse.”

The eight years have flown by, he says, and he is not put off by the changes here. Rather, he has been pleased to see the growing confidence and international profiles of Hong Kong artists. He even sees the endless red tape as a learning opportunity.

“The bureaucracy is another culture,” he says. “I find it fascinating because I had never experienced it before. So I have learned a lot about public accountability and it is very good training.”

Yokoyama, the design and architecture curator, came in 2016 from Stockholm, where she was head of exhibitions at Konstfack, the largest arts and design university college in Sweden, a country that, she jokes, probably knows more about M+ than anywhere else in Europe because Nittve, the museum’s founding director, is a Swede.

As a Japanese whose second language is Swedish, she is dedicated to drawing connections between different design traditions and showing how such histories speak to our daily life. And M+, for her, is the only institution in the world where an anti-Euro-American-centric viewpoint can develop without resorting to the nationalistic approaches of museums in places such as Japan and Korea.

“At M+, we are not looking at the web of connections just by country,” she says. “As an institution rooted in Hong Kong but with a global perspective, our approach is not binary. We do not present a juxtaposition of Western design history against modern-day China. Our lives have many parallels. It’s not just West and East.”

There may be a poignant reference to what has transpired since the 2019 protests, but it is a subtle one: a work by the artist Kacey Wong Kwok-choi. The label for his Paddling Home (2009) had to be updated at the last minute to reflect the fact that he is now based in Taichung, Taiwan, after the outspoken artist left Hong Kong earlier this year citing the national security law. But on the whole, you wouldn’t know that the city has just been through some of the most dramatic events in its history.

For Fung, who recalls the days when Hong Kong artists had great mistrust of the M+ project, the museum has two fundamental problems. “This is a museum that talks about contemporary visual culture. Visual culture changes every day, and change is faster now with social media,” she says. “So how can M+ keep up?

“It is very difficult because of the NSL. There are important things, like the Pillar of Shame, which commemorates [the 1989] Tiananmen Square [crackdown], that may be gone if nobody collects it now. When we are talking about history in 20 years’ time, where will today’s objects be?”

She also shares the belief of many others in the local art scene that the museum’s curatorial team does not have enough local Cantonese speakers. “You can’t just say to your curators, go and visit Sham Shui Po and do a bit of research on what local artists are up to these days,” she says. “I think M+ is a bit detached from local people, maybe because they speak mainly in English.”

But Chong counters that some detachment is necessary for a museum. “We always take a historical distance – a distance that allows for objectivity,” he says. “History shows that very few things are truly gone, and museums are not just about collecting. There’s a whole storytelling aspect to what we do and so we can address things in different ways.”

Fung agrees that M+ has a global perspective that results in a very different approach to that of local museums in the past: “Whether I like it or not, each of the earlier M+ exhibitions I went to always taught me something new. And I can’t say that about the existing local museums. There are never any strange, unexpected things there. But with M+ there are surprises that stimulate.”

As the museum LED wall lights up with a gigantic logo of M+ against the Kowloon skyline, the timing might finally be right for Raffel. She has just renewed her contract.

“I want to stay and enjoy the institution and the team taking it to the next stage, I want to experience the pleasure of working here beyond the opening preparations,” she says. “Just come and see it and decide for yourself.”

Show, not tell

For the museum opening, Doryun Chong, deputy director and chief curator of M+, is in charge of a relatively modest gallery, but one with the task of laying out, through objects alone, the core philosophy of this massive institution.

The Courtyard Galleries on the second floor, home to “The Dream of the Museum” exhibition, is set deep in the heart of the horizontal slab of the inverted T-shaped building. It is windowless and covered from floor to ceiling in bamboo panelling.

The next gallery appears to be an about-turn, back to the traditional. On closer inspection, however, it is apparent that the Chinese ink paintings by Peng Wei and Hao Liang have their own contemporary, conceptual twists, as does the Tibetan Buddhist thangka that Zheng Guogu re-coloured in 2013.

The room is designed so that the works are displayed in four sections arranged in the shape of a windmill. The audience gets a jolt at each turn, confronted by deliberate, playful incongruity.

Behind the Buddhist thangka is a wonderful juxtaposition of Ono’s all-white chess set that she made for Duchamp (called rather cleverly Play it by Trust) and a photograph that features a chess set by another Japanese artist, Morimura Yasumasa. In it, Yasumasa is dressed up as both Los Angeles writer Eve Babitz and a much older Duchamp, restaging a 1963 chess match between the two in which Babitz played nude. It’s all very meta, full of historical art references.

Turn around, and you see a wall covered in Andy Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle screen prints (1976-77), the brightly coloured symbol of communism, which may possibly have a fresh resonance for the Hong Kong audience today. (And a glass case containing the original hammer and sickle he bought from a hardware store.)

Chong says he could have stuck with a more typical “the making of the museum” exhibition with the requisite architectural models. “But it seems a bit silly when we are actually standing inside the building.” And so instead, he has opted for a show, not tell, approach that traces a lineage of conceptual art from Duchamp onwards.

The result is a smorgasbord of surprises, and an impressive taster of a broad and diverse museum collection.