History of real pirates who dressed as passengers to hijack and plunder Hong Kong ships in the South China Sea

- The ‘passenger ploy’ tactic used in the early 20th century saw many a steamer violently looted, leaving colonial Hong Kong’s governor scrambling to stop it

On the afternoon of Sunday, November 19, 1922, British coastal steamer the Sui An departed Macau on its regular 50-mile journey to Hong Kong. The ship was at capacity, carrying 400 Chinese and a further 60 European passengers, most of the former in second class and the latter, with a few seemingly wealthier Chinese dressed in Western suits, in first.

The Sui An was operated by the Hong Kong, Canton & Macao Steamboat Company and was a familiar sight in Victoria Harbour. An hour or so out of Macau, and just beyond the reach of the Portuguese Navy’s anti-piracy patrols, perhaps as many as 65 Chinese passengers, both men and women, revealed themselves to be heavily armed pirates.

Their leader, wearing a tailored suit and accompanied by a smartly dressed woman, strolled out of first class, pulled out a revolver, fired it into the air and took command.

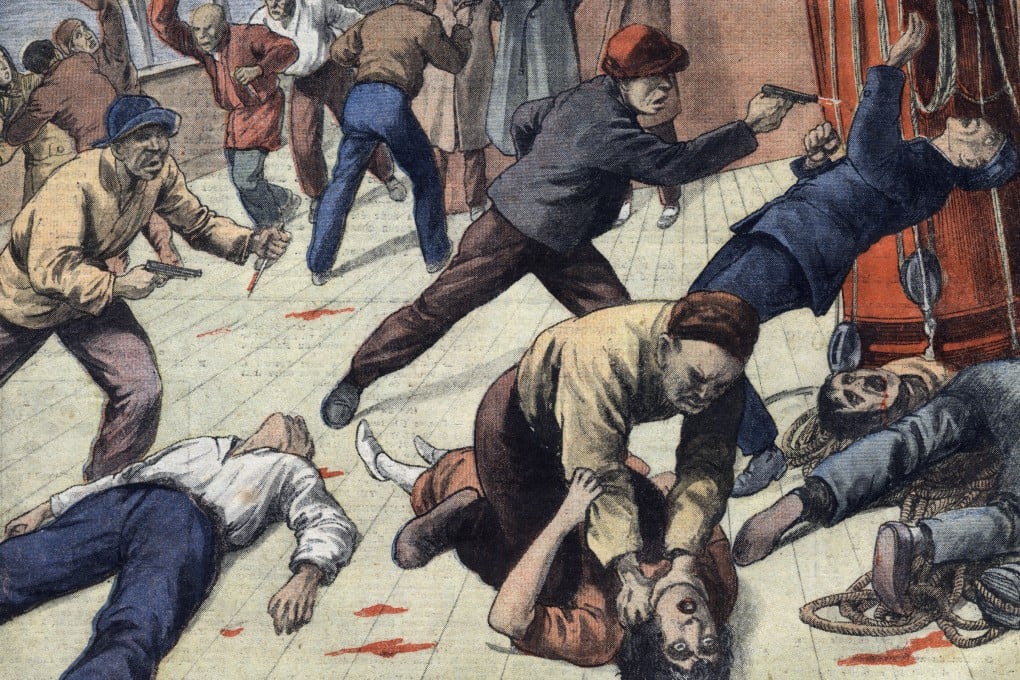

Badly outnumbered, the Sui An’s crew put up a fight, but the pirates were ruthless. Two armed Indian guards were targeted, quickly killed and their bodies thrown overboard.

In the resulting melee a European passenger who resisted was shot three times. A French Jesuit priest who stepped forward and attempted to mediate with the pirates was clubbed unconscious for his trouble.

A Chinese sergeant of the Sui An’s guard and another watchman were both badly wounded attempting to protect the commanding officer, Captain Birss, who was shot in the back and then knocked unconscious with a revolver butt. Three of the pirate raiders were shot and wounded.