The Chinatown Stalin made a ghost town: Millionka in Vladivostok, home for labourers who built the Russian Far East

- Tens of thousands of Chinese – labourers, refugees – called the Chinatown in Russia’s easternmost city home for decades until Stalin ordered it ‘liquidated’

Russian newspapers noted Chinese peddlers of paper flowers and other cheap goods at every station all the way to St Petersburg and, as with all who sought to exploit the natural wealth and new opportunities in Vladivostok, the Russian Empire’s most easterly city, many Chinese workers decided to settle there, too.

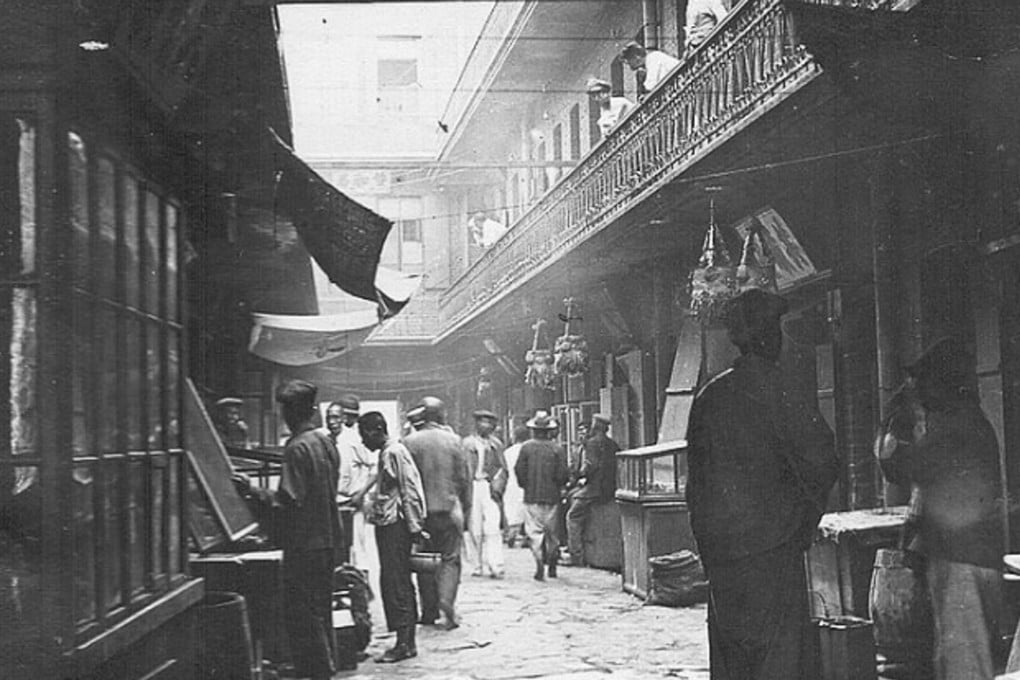

The Vladivostok district most of them would come to call home – an area that would soon become known as Millionka – was next to the busy port. Initially intended for the city’s expanding mercantile middle class, it consisted of well-built, three-storey red-brick buildings, replete with ornate arches and balconies. However, with views of a functioning port – rather than a romantic sea vista – the settlement somehow never attracted its target market.

As the area’s population swelled, so illegally built wooden extensions appeared in its cul-de-sacs. Lodging houses, basic dosshouses in many instances, were subdivided again and again into labyrinths of small dormitories equipped with bunk beds for Chinese workers. The buildings began to fall into disrepair, rubbish piled high, and the overloaded drains backed up. Millionka became a slum.

Legends grew about a network of tunnels beneath the district, “oriental cellars” for opium smoking and gambling. According to the local police, there were perhaps as many as 40 organised gambling and prostitution parlours.