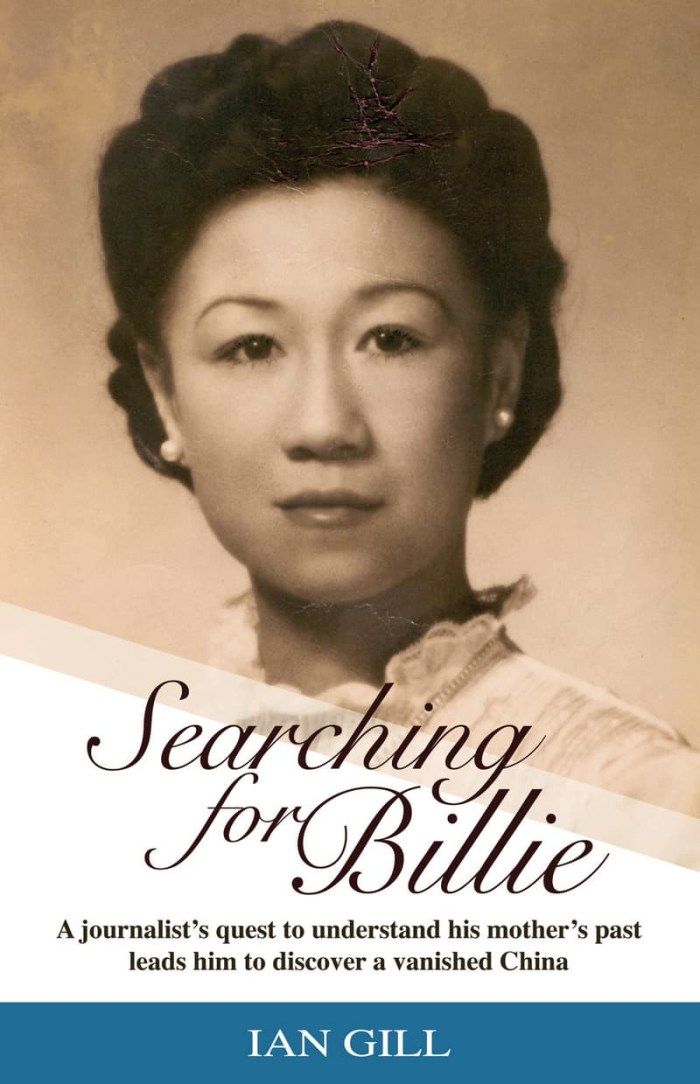

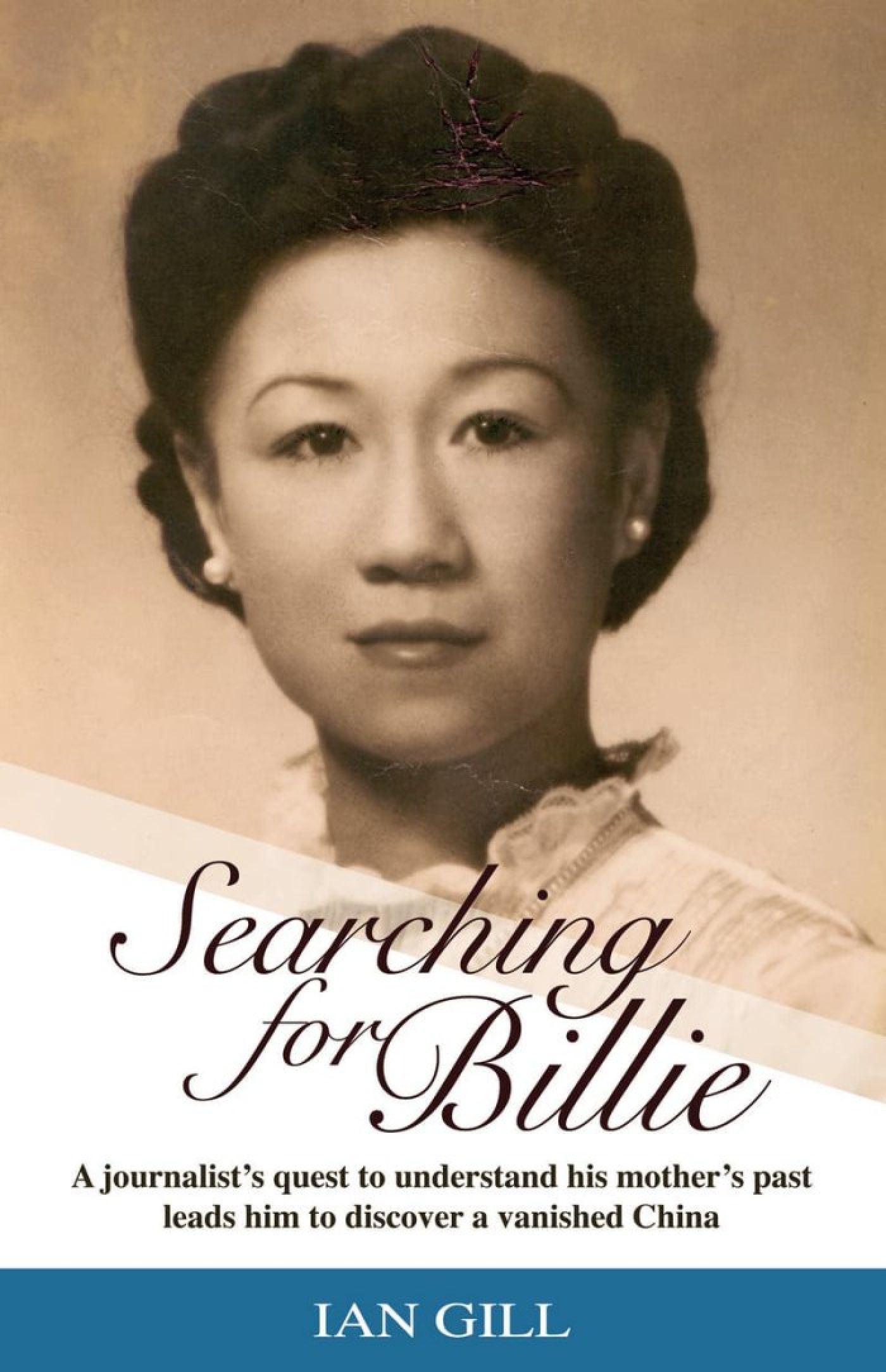

- An excerpt from Searching for Billie sheds light on the life of the author’s mother at Hong Kong’s Stanley camp during the chaos at the end of World War II

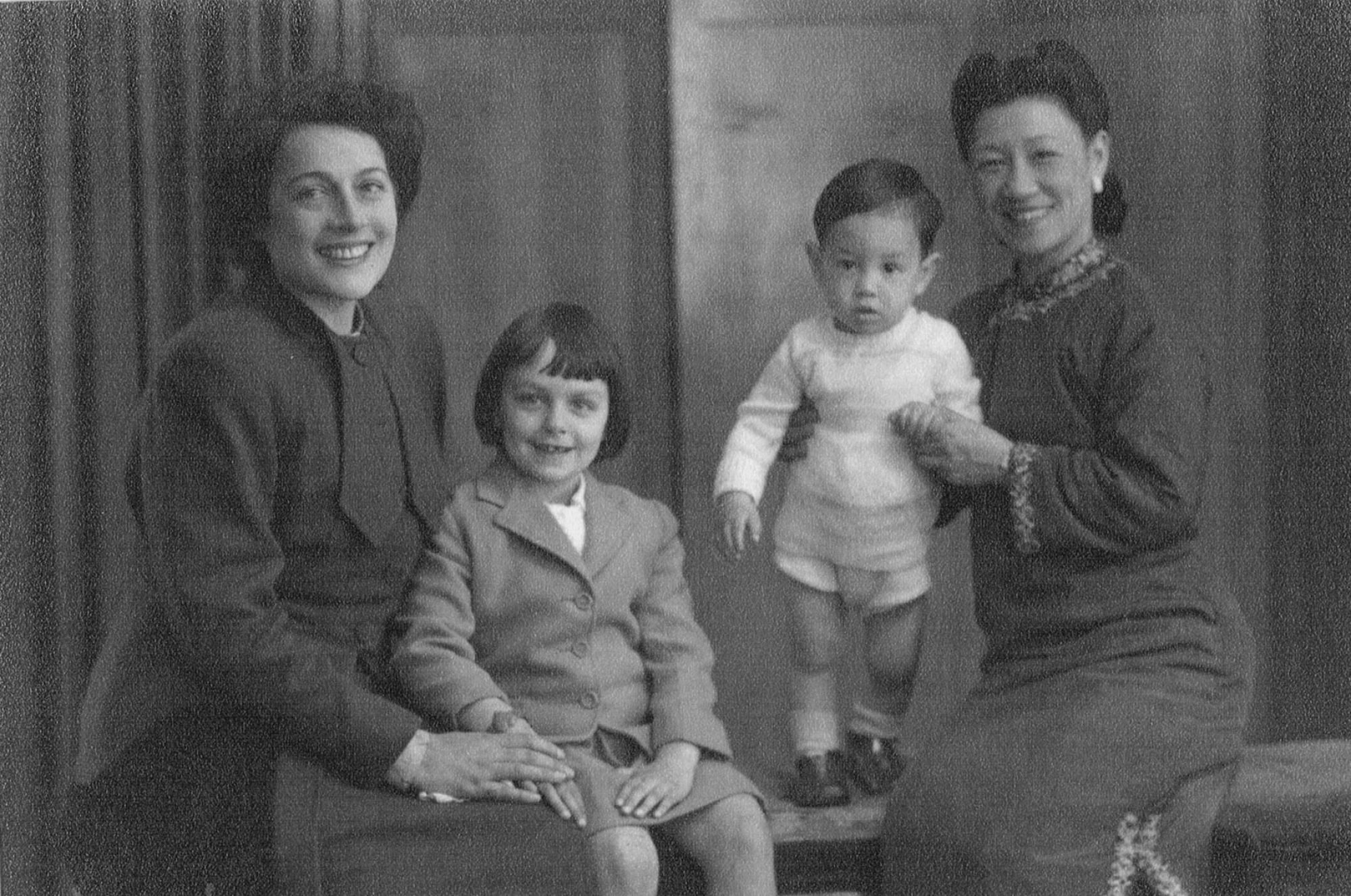

Ian Gill’s first visit to Hong Kong, in 1975, took an unexpected turn when he met the friends, colleagues and fellow ex-prisoners of war of his mother, Louise Mary “Billie” Gill, lifting the veil on her tumultuous past in Hong Kong and Shanghai.

In this excerpt from his book Searching for Billie, he describes the bittersweet period after liberation from internment:

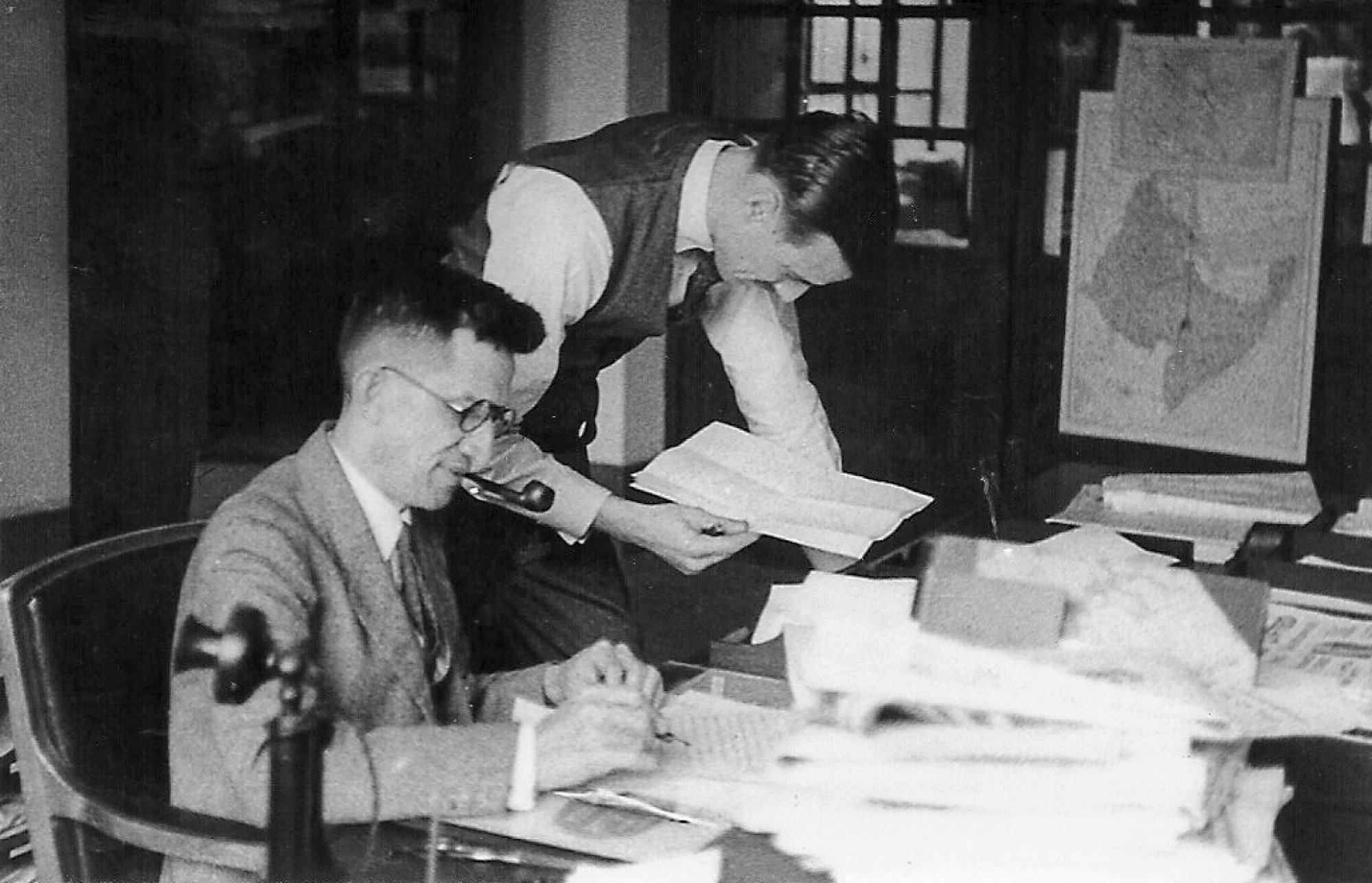

With the Japanese still around, George Giffen and Henry “Harry” Ching camped in the office, with George regretting he had not brought his bedding from Stanley (internment camp). They were not friends, but George thought highly of the Australian-born Eurasian editor.

“Ching was a fine chap, he had integrity and I respected him,” George said. “In the office [of the South China Morning Post, in Wyndham Street], his favourites were Australians. He liked their rough style. He had no time for the English chaps and I was the only English fellow then.

“He told me he had had a lousy time in the war; he was beaten up by everybody.”

Like all of Hong Kong, they were anxiously awaiting the arrival of military forces to end the tense, uneasy limbo where no one was in charge.

Uncovering the truth behind a Chinese-American soldier’s World War II death

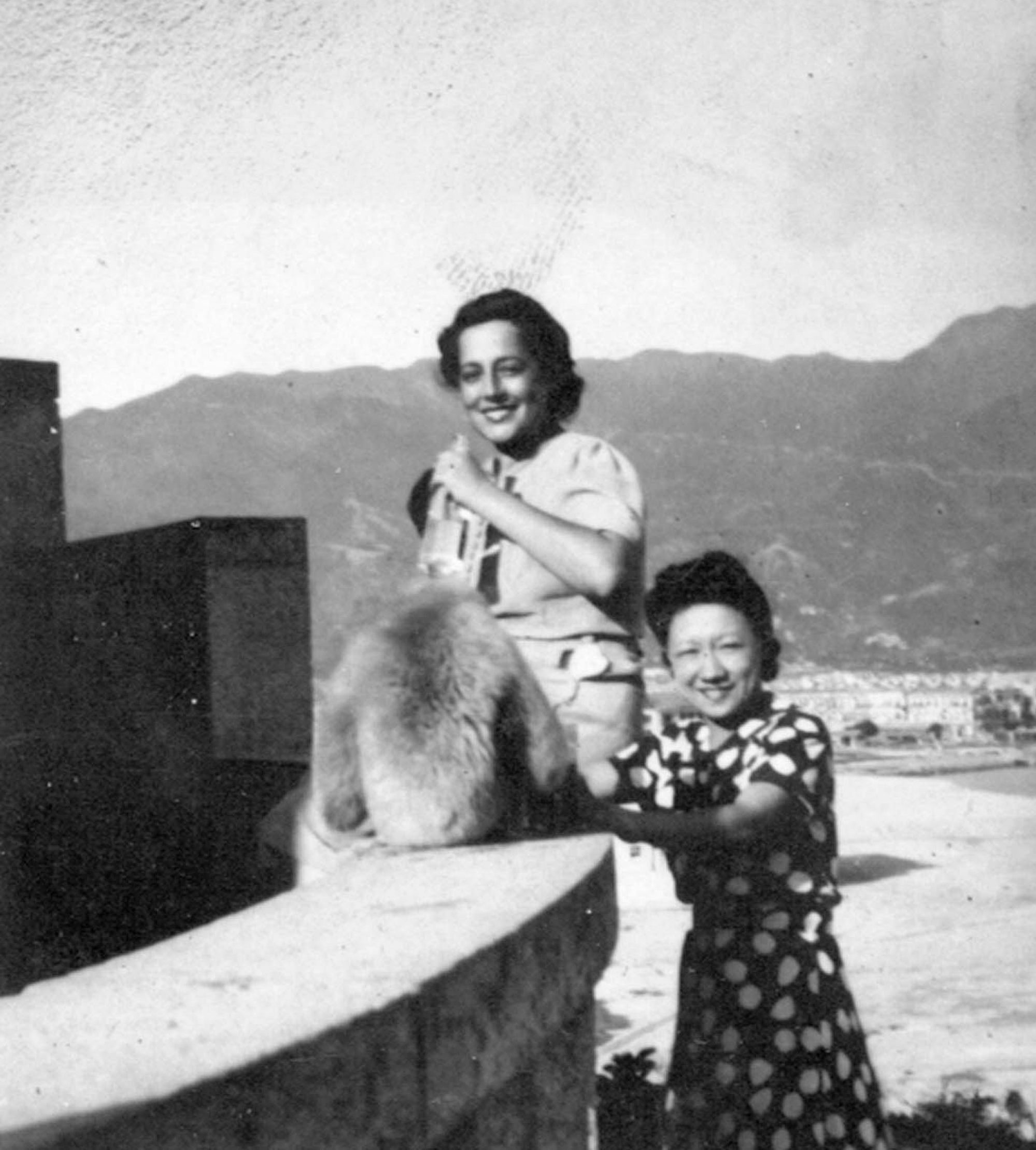

Although the food situation had improved, Stanley internee Billie (Louise Mary Gill) watched with wonder when, on August 29, 1945, the United States Air Force dropped parachutes with food and medical supplies.

“While we looked on in disbelief, the first fly pass of planes roared over our heads, doing the victory roll again and again,” Billie would say later. “Then each of the planes released coloured parachutes with trunks full of medicines and Red Cross parcels tied to them.

“This beautiful heaven-sent rainfall went on for hours, the trunks landing all over the camp. We were so well disciplined by then that squads were immediately formed to collect the trunks from rooftops and places where they had landed. It was tremendous.”

At the newspaper office on August 30, 1945, Harry and George set about preparing their first full issue under a cloud of uncertainty. Many were still unsure which force would reach the colony first – the Chinese army or the British or American navies.

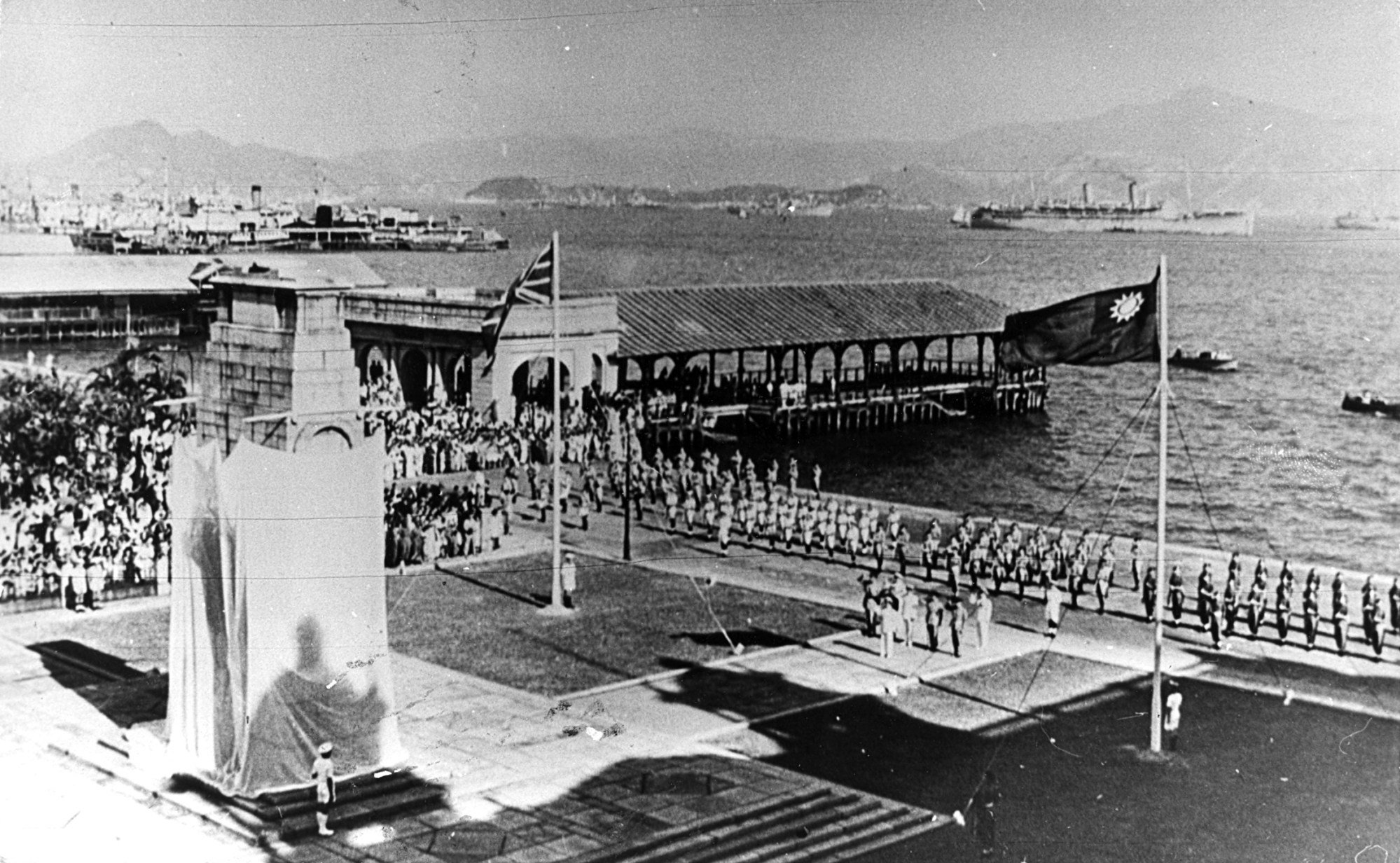

It was George who spotted the warships. He had been out and about since early morning and he rushed into the office shouting, “The British fleet is coming in.”

George typed out his story on the arrival of Admiral Cecil Harcourt on the cruiser Swiftsure – it was printed as a single-page leaflet to be distributed free to passers-by, and was on the streets of Central by the afternoon, with copies reaching Stanley later.

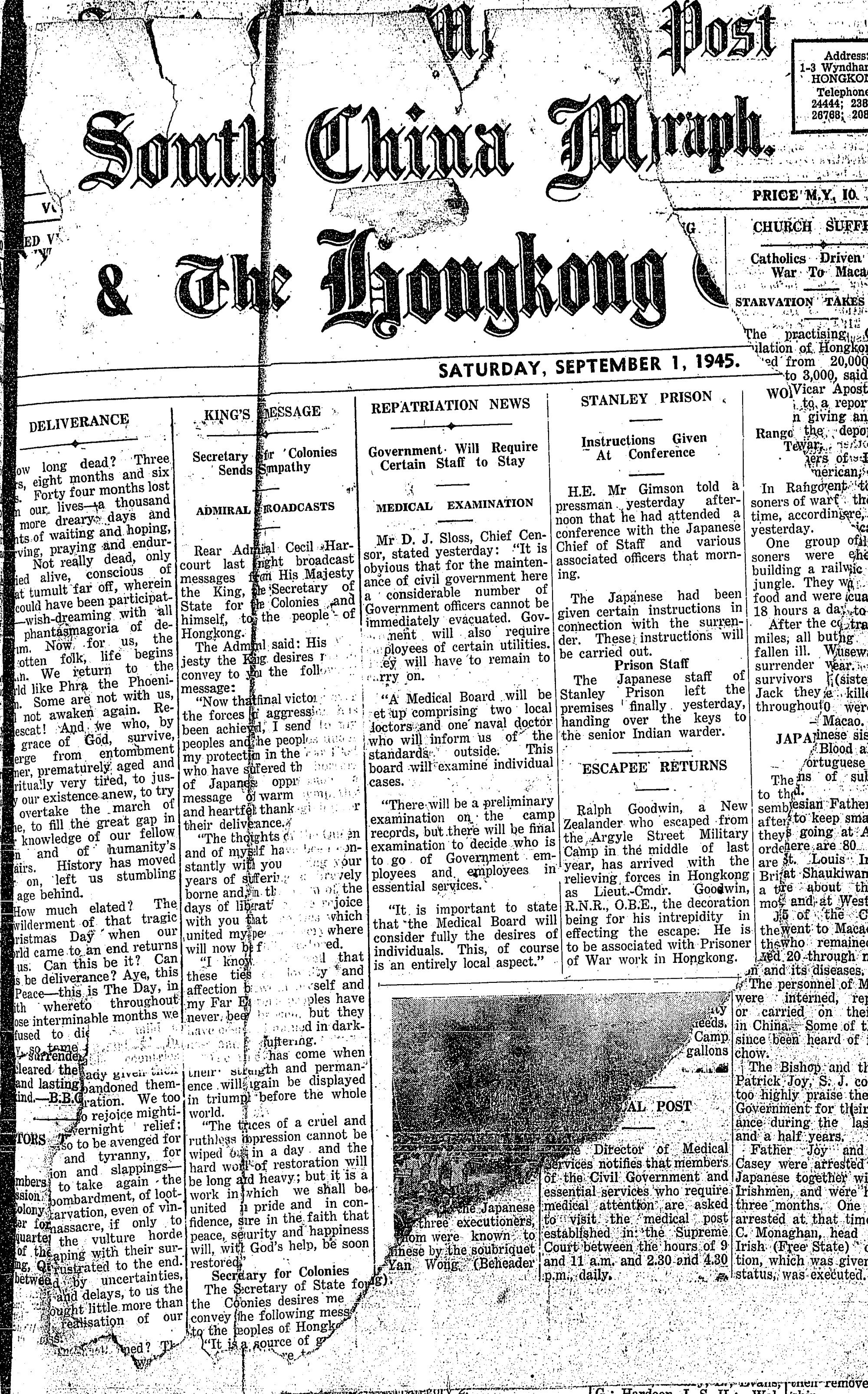

The next day, Harry and George, assisted by John Luke and Eric MacNider, produced the first full post-war issue under the combined masthead of the South China Morning Post and the Hongkong Telegraph.

To print the paper, George had to “walk up and down Wyndham Street, asking people to turn off their fans and lights so that we could get more power and get the press to run – and they obliged”, he said.

“It was a wild time because everybody was celebrating. I had to go around the city in a rickshaw and visit the Chinese paper firms and try and confiscate rolls of newsprint so that we could go to press.”

Frederick Franklin, the assistant general manager of the Post, arrived as army press liaison officer with an officer from the Hong Kong Police and ordered the Japanese to leave. They did, reluctantly, taking their Japanese type but leaving a large stock of rice, which Franklin found useful in paying the Chinese staff during the next few days.

George would be on the newspaper’s masthead as publisher for the next three months and would run the company for 10 weeks after Franklin left with health issues.

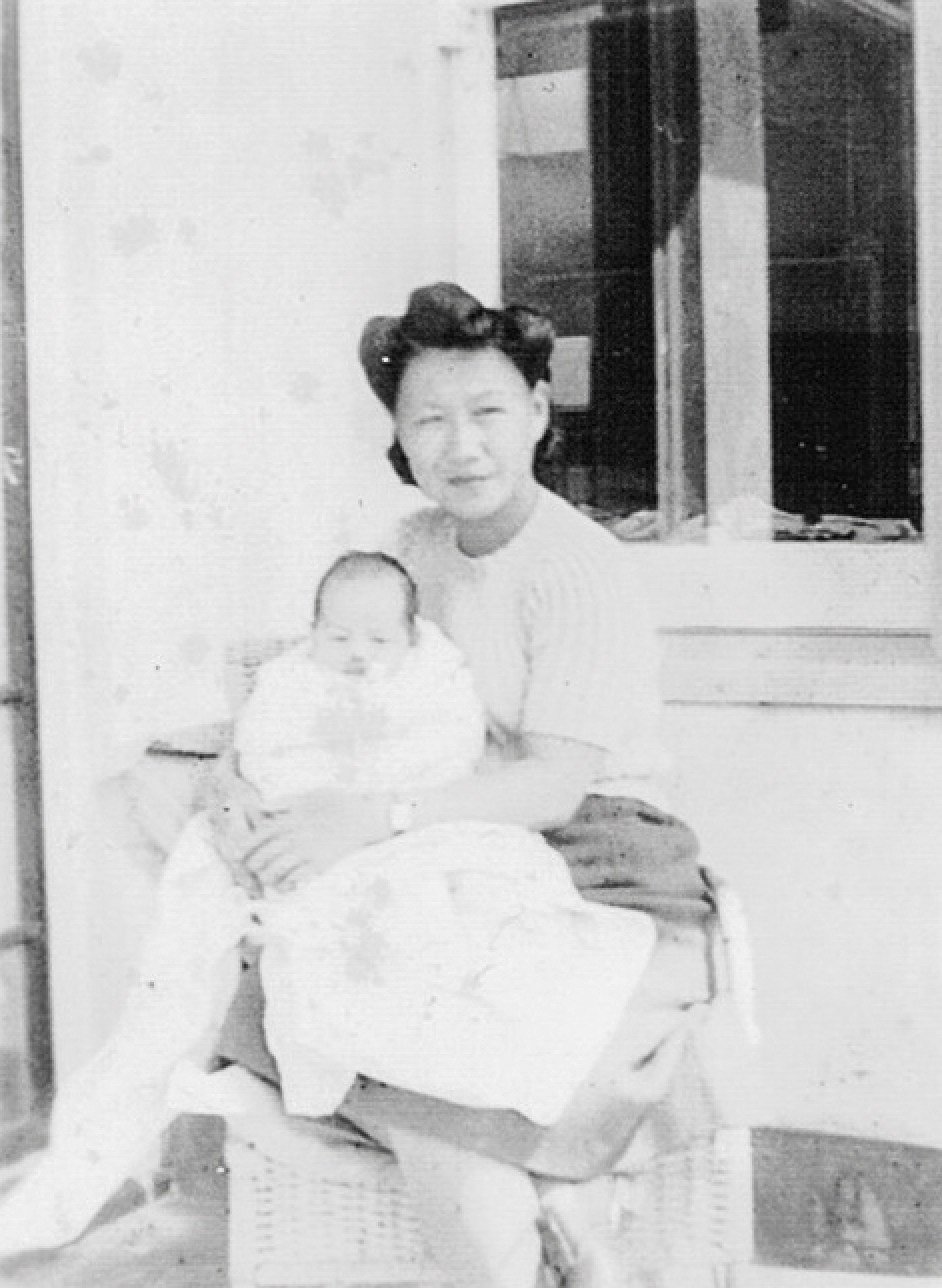

In Stanley, Billie read the paper with pride but she missed George terribly. Her head was swirling with thoughts of the future, not least the baby that was due in November and needed a Caesarean delivery.

On August 31, she saw Harcourt, newly appointed commander-in-chief and governor of Hong Kong, arrive in Stanley with his aides. Billie stared at the big, strapping navy men, who made her acutely aware of her skeletal frame.

She saw jeeps for the first time, a stark symbol of how the outside world had moved on in some ways while she had been at a standstill.

Washing had been taken down from camp buildings and a Union Jack hoisted as Harcourt addressed the internees: “The motive that has inspired my men, all the Bluejackets, to get here as quickly as possible, which we have done, has really been you people.”

The assembled gathering sang God Save the King and other nationals raised their flags, which were lowered to half-mast as a bugler sounded The Last Post in memory of the departed. Internees sang Oh God, Our Help in Ages Past and planes flew low in salute.

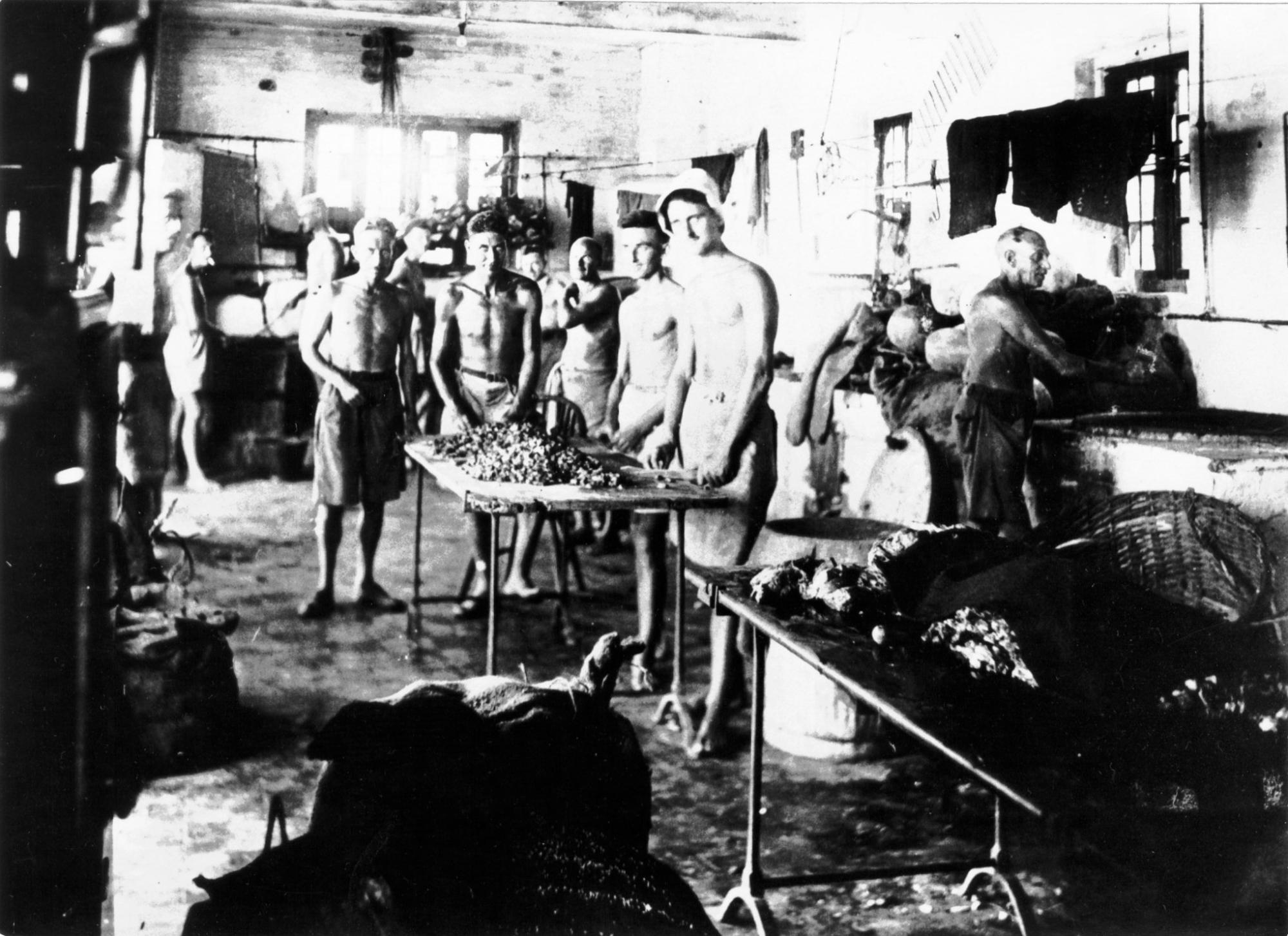

For Billie, liberation brought unexpected stress. Supplies of Red Cross parcels found in Japanese stores were distributed, but the richer diet caused those who gorged themselves on tinned vegetables and bully beef to be violently sick.

After dreaming of steak for years, Billie found the taste of beef bland and repelling and she hankered for the pungent flavour of salted fish. Gradually, she began to regain her strength. Activities such as climbing the footpath became less exhausting. Her skin shed its pallid colour and her face looked less gaunt.

These were terrible days of confusion and chaos as evacuation plans were madeBillie Gill on the period following the Japanese surrender

To her relief, her memory started to return, like an old friend. But with it came psychological challenges as initial jubilation gave way to anxiety about the future.

For so long, she had been intent on surviving day to day without having to make plans for the morrow and now, suddenly, the gates opened onto a big wide world and she wondered, with many moments of doubt, whether she could summon the strength to learn to live and work all over again.

The arrival of the British fleet ended the uneasy truce between the Japanese, the prisoners of war and the Chinese, and saw pent-up feelings erupt.

Many Chinese sought revenge for years of starvation, forced deportations and random violence. After recognising the executioner from Stanley on a ferry, a mob towed him across the harbour with a rope around his neck.

Billie saw ex-POWs settling scores, too, getting drunk and going to the jail to beat up their former captors.

She saw Stanley’s egalitarianism corrode as some reverted to patronising the Chinese and Eurasians.

With scarcity relegated to the past, the value of items changed dramatically. Scraps of food and cigarettes, once highly prized, were now discarded casually. Instead of scrounging, people were littering the camp.

On September 3, internees were allowed to write one letter and Billie sat down and penned a long and lucid airmail to Mickey (American journalist Emily Hahn). George had told her he had seen Charles (Boxer, Hahn’s soon-to-be husband who worked for British intelligence) and he was safe.

Unbeknown to Billie, Charles had been transferred from Stanley three months earlier to a miserable prison in Canton, where he had shared a vermin-infested cell. Now he was back and looking remarkably well after his ordeal.

He had written to Billie, asking about the last unprinted article he had submitted to T’ien Hsia magazine (its editor, Wen Yuan-ning, had hired Billie in Shanghai in 1935 as office manager and they had both left for Hong Kong in 1937 during the Sino-Japanese war to restart T’ien Hsia).

Billie’s letter reveals her state of mind after emerging, like Rip Van Winkle, from a long sleep. She took her cue from a brilliant editorial that appeared in the first full edition of the South China Morning Post, on September 1. She thought George wrote it, but in fact Harry had penned it. Billie felt it reflected her condition well.

Under the heading “Deliverance” the editorial opened with: “How long dead? Three years, eight months and six days. Forty-four months lost from our lives – a thousand and more dreary days and nights of waiting and hoping, starving, praying and enduring. Not really dead, only buried alive, conscious of great tumult far off, wherein we could have been participating – wish-dreaming with all the phantasmagoria of delirium.

“Now for us, the forgotten folk, life begins again.”

Billie told Mickey: “The happenings of the last three weeks have been practically beyond our powers of realisation. I still cannot feel or believe that everything is over, but that is partly because I am still sitting here in the camp.

“But the things that are taking place every single moment are real enough and soon, I suppose, I shall really be out of these barbwires.

“Even being told that one can write an uncensored, unlimited (at least three pages) airmail letter is something of a long, almost-forgotten past. But the brain is slowly beginning to function and my first thought of contact is with you.

Photos of Hong Kong after World War II capture the city in its grimy glory

“I really don’t know how I lived after that. Internment conditions and the struggle to exist were bad enough, but after I lost Brian, I felt I had lost everything. And I did. My mind was paralysed.

“But time slowly softened things and George, by his devotion and friendship, gradually fitted into my life like a beautiful pattern on a tapestry. The world before and the world outside faded. We only knew one world and that was here and it seemed that it would go on forever to eternity.

“So we decided to have a baby. Now the war is over and I am expecting this baby either at the end of this month of October or on the actual date it is due, which is November 7.

“The date is vague because of the state of my health and because it will have to be a Caesarean.”

Billie went on: “I want very much to get away from here and give this child a good start in life with food that I have hitherto not had in my system. But the final wrench from George is going to be difficult.

“However, I have had a week to think about it all seriously and from this new light. He was among the first of the essential people required to go into town and for five days we have had the Post back with a vengeance.

“I have been very proud of his work these last few days, particularly as he has had to do everything single-handed. Also, his worries are going to begin and, rather than add to them, I feel I must get away and make a life for myself away from him.

“You remember he has a wife and daughter in Canada. They’ve got to be considered now. He doesn’t know how the land lies until he sees them again. So that is one reason why I want to get away and leave him free to fulfil his obligations first towards them.

“As for myself and this baby of his on the way, I feel the future will unfold itself.”

She said Harry had told her all the T’ien Hsia staff had managed to leave Hong Kong and that Wen was “a big shot, representing China at various peace missions”.

“Can you help me please, Mickey?” Billie asked. “Please let Wen know I am alive and by January next year hope to be back to normal and I want something to do in England or America. I want to get a new start in life before I come back to China.

“I feel as though I have been buried alive for three years and as soon as I am physically fit, I want to do things. This baby is giving me the incentive. I didn’t want to do anything, but just die for a long time. Now I feel I have everything to live for.”

The letter’s tone was calm, but her anxiety rose over the following days as George failed to return. George was staying at the Gloucester Hotel, sharing a room, he said, with “an East Indian who had this shirt with gold buttons and a chain”.

He wrote to Billie on September 7: “I got your last chits when I returned to the hotel at 8.30am. I can understand how upsetting all the changes must be to you.” He was referring to the hurried repatriation arrangements being made for internees.

“These were terrible days of confusion and chaos as evacuation plans were made,” Billie would say later. “At first, we were told we would all be sent to special camps in Manila, where we would be sorted out and taken to our respective homes. Then I was told I would be on the troopship, the Empress of Australia, which was taking internees to England.”

On the same day, a Friday, at 3pm, George wrote a letter to Billie: “I received everything safely and am indeed grateful. I learn now that you won’t be going till Tuesday. I don’t think the information at your end is so reliable as it is here.

“I am borrowing the car to come out very early Sunday morning. I should arrive at 6.45, see room 31 till 7.30am, you till 8.30am, after which I must get back. I am quite sure of this programme so don’t come into town – it is such an anxiety getting you back comfortably and getting off time to look after you here.

“My love, my dear, and if the most urgent thing happened and you were transported away without us meeting again, don’t forget that we shall certainly meet sometime and I will always remember you and baby. With love, George.”

Some of her friends were leaving camp and Billie asked George that if she could not see him in town could he come out to Stanley. At 2am that Sunday, George replied: “My dear girl, I am sorry to say that my arrangements for coming early this a.m. have fallen flat as another party, with equal rights to it, has taken the car. Furthermore, we are bringing out 3 editions today and I shall not have a moment to spare.

“I know it is cruel that work should intervene but duty will prevail over sentiment, my dear, and you will be finer in my eyes if you accept the position.

“I can’t come out unless a fluke gives me the chance on Monday and I shan’t be able to spend any time with you if you come to town.

“Please believe that I am not stalling but am stating the cold facts. I have only spent the hours from 2am to 7am in my bed since I came out and have had no diversions.”

George went on: “I am fit as a fiddle so I suppose work suits me. You must go in for being a mother and I know you will be a splendid one. I have received a pile of things from you and milk powder of all things. Please don’t go without as I am getting 3 sq meals a day now.

“I am thinking of both of you and wishing you comfort of mind and body. Do not despair of seeing me out there as even Tuesday might not be too late. With love, George.”

But they knew the time was running out as Billie was due be taken to the evacuation ship the following day. On Monday, September 10, as Billie was to be transferred to the Empress of Australia, she received another message from George.

It was still not too late. If he had changed his mind and asked her to stay, she would. George scribbled that he planned to see Billie – from another vessel.

“A hurried note to say farewell,” he said. “I hope to see you from the Kempenfelt from which I have managed to get a trip with the admiral to see you off.

“Try and imagine that HMS Kempenfelt has especially come out to bring me nearer to you. Dry your eyes and rest. Believe me, there will be lovely things in store for you when baby is born and you’re reunited with friends.

“Goodbye my dear for now. Don’t regret Stanley and think not too harshly of me who have [sic] done you so much harm and brought you so little happiness. With love from George.”

The internees’ departure from Stanley was almost as chaotic as their arrival, only this time they were in high spirits as they were on their way home. Billie did not share their exhilaration.

In just a few days, the love that had bloomed in the shadow of war was wilting in the sunlight of peace. She was alone, possessing only what she was wearing and could carry.

One of her biggest concerns was that she could not carry out the family mementoes Ah Chun (an amah) had helped her bring into camp.

She had to choose what to leave behind and, with a wrench, she gave the precious but heavy family Bible to Brian Fay, the police officer she had helped rehabilitate.

Clutching her belongings, she joined the corvette that carried internees to Junk Bay, outside the eastern end of Hong Kong harbour, where the Empress of Australia was anchored.

The Empress was a Canadian Pacific ocean liner that had been converted into a troopship and was painted warship grey.

Billie walked up the gangway to join 1,000 other ex-POWs. It was crowded way above capacity, with women and children squeezed into the cabins and men camped out on the decks.

Billie shared a cabin with up to a dozen women and children from Stanley. At intervals, she would make her way to the deck to see if there was any sign of HMS Kempenfelt.

She was leaving Hong Kong without the lover who had become her rock. Even as she boarded, she thought she was bound for England, where her sister Jessie lived. She had no inkling that her voyage would land her at the opposite side of the world.

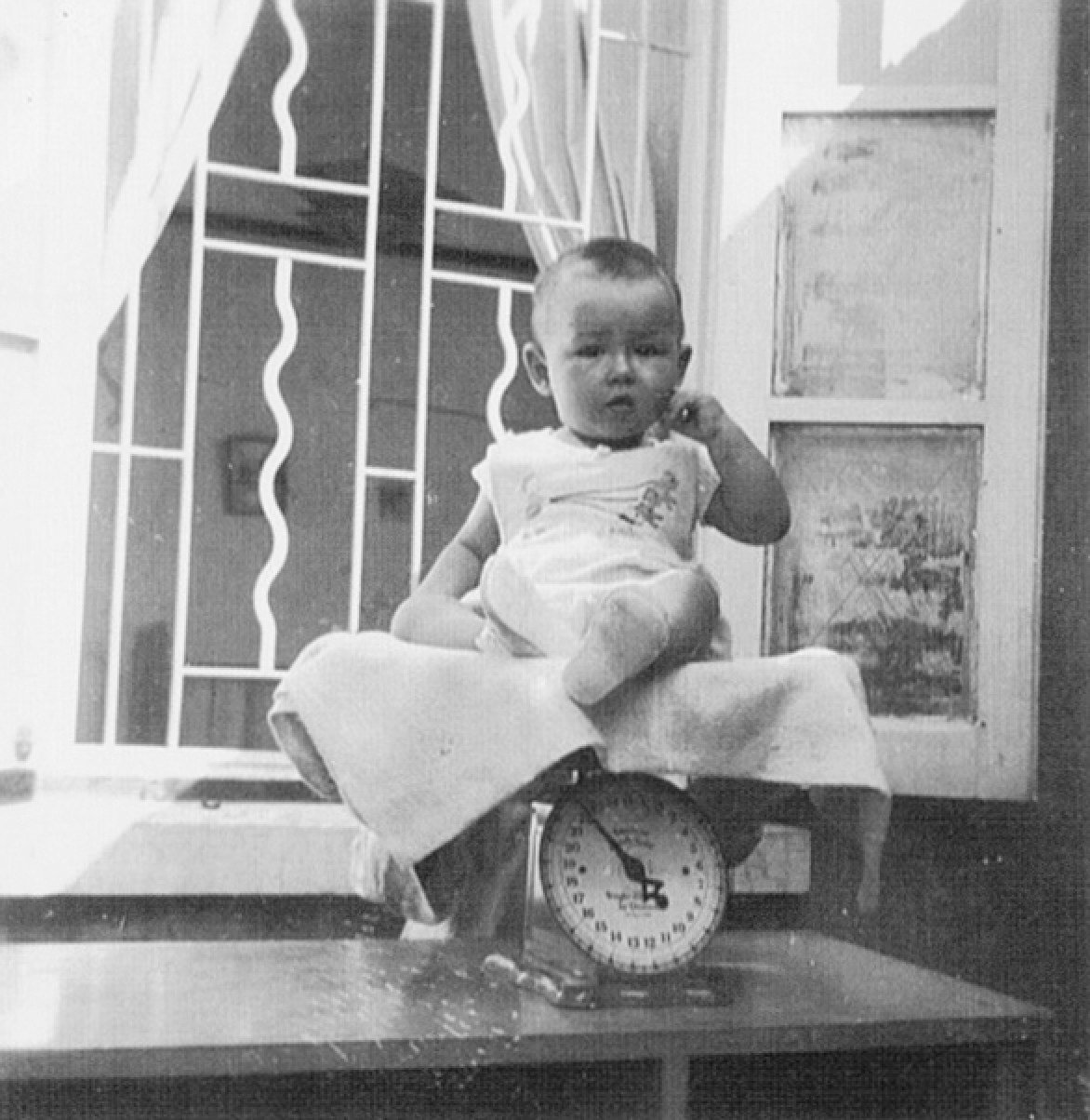

The author is the child Billie was pregnant with in Stanley internment camp. He was born in New Zealand on October 25, 1945.

As part of the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, Ian Gill will be at the Fringe Club, in Central, talking about his book, Searching for Billie, on March 9 (1pm-2pm) and taking part in an event called “In Conversation: Historical Hong Kong – Vaudine England (Fortunes Bazaar) & Ian Gill (Searching for Billie)” on March 10 (11.30am).

Searching for Billie is published by Blacksmith Books.