The Chinese Bible: how it was translated, and the phrases it introduced to the Chinese language

- When Christians produced a definitive Mandarin translation of the Bible, the Chinese Union Version, they consulted ancient Greek texts as well as editions in English

- Their translations of metaphors and allegories introduced to China phrases such as sacrificial lamb and a tooth for a tooth whose biblical origins are forgotten today

On December 25, Christians around the world (apart from Orthodox Christians, who fete the occasion on January 7) will celebrate the birth of Jesus, or Yesu in Mandarin. When I was younger, I attended a non-denominational Protestant church that had both Chinese- and English-speaking congregations, and the differences in some biblical names between the two languages often puzzled me. How did “Jesus” become “Yesu” in Mandarin? How did “James” turn into “Yage” and, most boggling to my young mind, how could “Eve” transfigure into “Xiawa”?

Years later, I learned that the Chinese Bible was not translated solely from the English language, but from various sources. The Chinese names of the aforementioned biblical figures make sense when one realises that they might have been transliterated from “Iesus” in Latin, or “Ya’qob” and “Hawwah” in Hebrew.

What happened to China’s early Christians and their heretic doctrine?

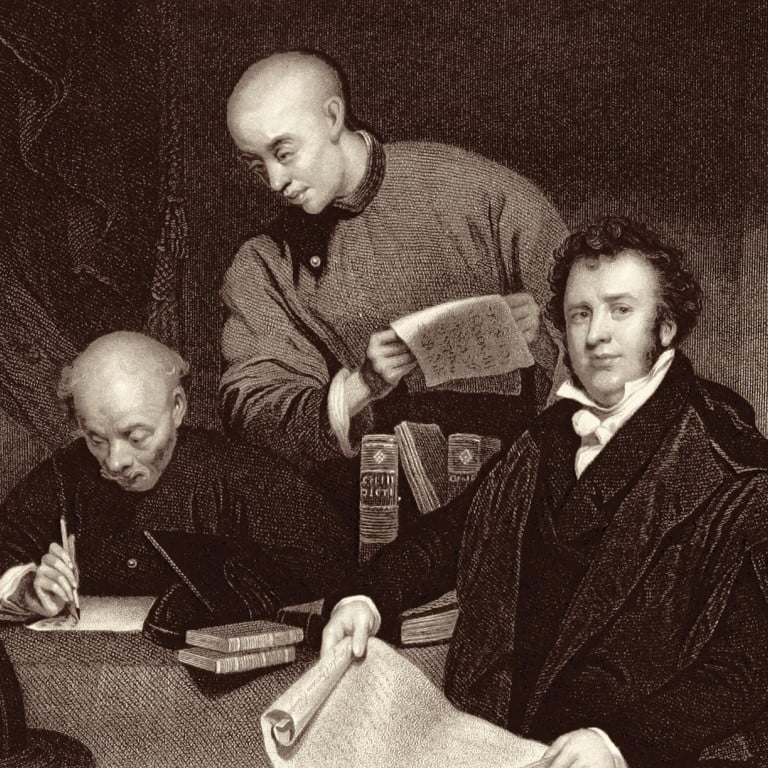

There had been various Chinese translations of the Bible, or parts of it, before the 20th century, but the lack of a standardised version was not conducive to the saving of Chinese souls. In 1890, a group of English-speaking missionaries from various Protestant denominations decided to produce an accepted Chinese translation. Two were completed in 1919: one in classical Chinese, another in the vernacular.

Although the translators of the latter used the English Revised Version of the Bible as their primary source text, they also referred to ancient texts in written in Greek, as well as other versions, such as the King James Bible.

The translators, themselves British, American and Chinese Christians, adhered to several rules during their work: they had to use the common language, Mandarin, instead of regional dialects; their translation should be easily understood by everyone regardless of the level of their education; the translated text must be faithful to the original but also read well in Chinese; and any allegories or metaphors should be translated as they were and not rendered into forms that were familiar to Chinese readers. The inherent contradiction represented by the last two rules underscores the difficulties of rendering a faithful translation of the good book, or indeed, of any book.

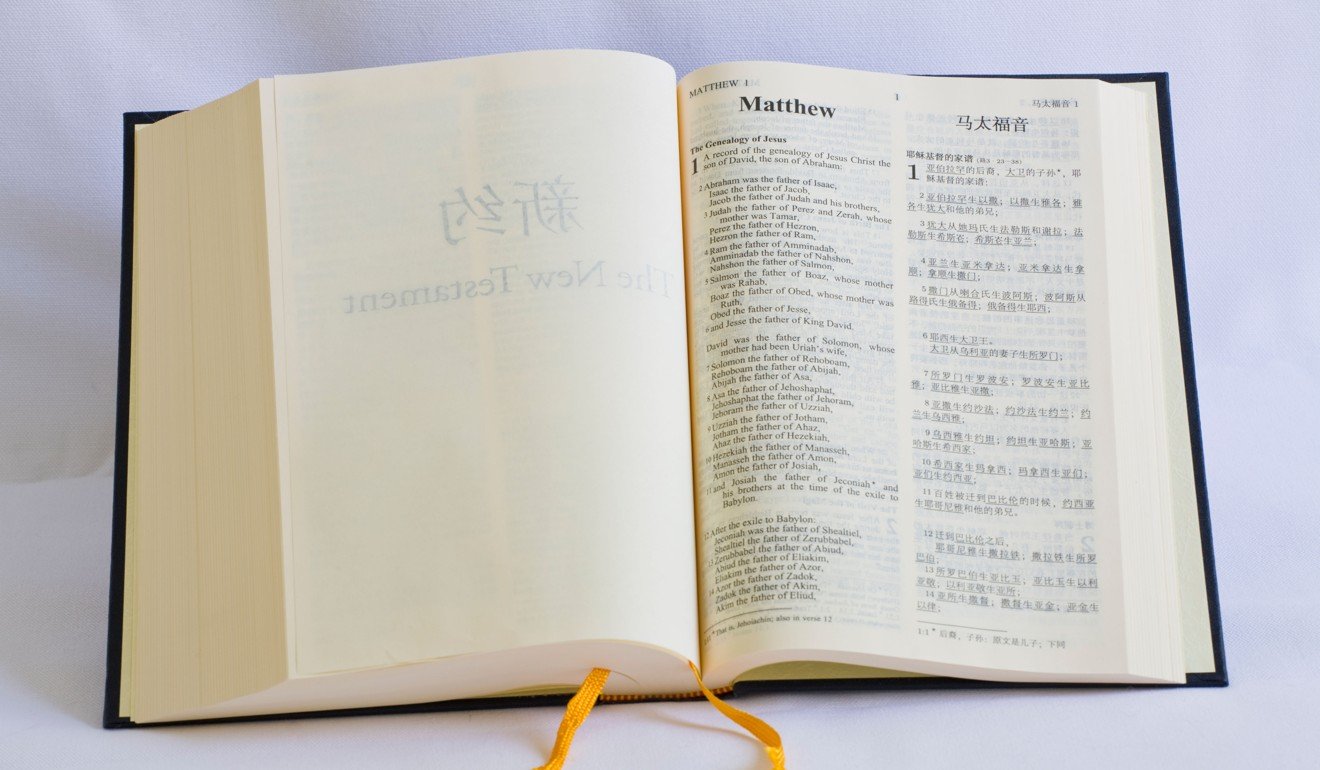

Of the two translations, the classical Chinese Bible gradually fell out of popular use. In the early 20th century, especially after the May Fourth Movement and the New Culture Movement, there was a seismic shift from the use of classical to vernacular in written Chinese. The Bible used by most Chinese Protestants today, known as the Chinese Union Version (CUV), is the vernacular translation. The Revised Chinese Union Version of the Bible, which made tweaks to the original CUV, was completed only a few years ago in 2010, and was consecrated at St John’s Cathedral in Hong Kong that year.

Just as Buddhist scriptures had done centuries before, the Christian Bible introduced neologisms into the Chinese language through its translation. Phrases like yiya huanya (“a tooth for a tooth”) and daizui gaoyang (“sacrificial lamb”) have become part of the Chinese language, to the extent that many Chinese today do not realise they are biblical in origin.

Christians believe the Bible to be written by authors whose pens were guided by the invisible hand of God. We do not know if translators are similarly piloted. The history of biblical translation, and the history of the Bible itself, suggests a surfeit of human involvement in deciding what is divine. But for those who truly believe that the divine governs human history, the uncomfortable questions that arise from flawed translations and textual inconsistencies can be filed away under “faith”, which, in its genuine form, is a beautiful thing.