China’s embrace of electronic payments is the latest in a long history of smart money innovations

- Paper money transactions began in the ninth century, with promissory notes carried by Chinese itinerant merchants

- Banknotes lightened the burden of countless coins, just as e-payments promise to do

My main issue with visiting mainland China these days is the inconvenience of paying for goods and services, which is ironic given the ubiquity of cashless payment platforms such as WeChat Pay and Alipay. Let me explain. As a foreigner without a Chinese bank account, it is difficult, though not impossible, to link up the relevant apps to make payments. I gave up after several attempts,concluding my five-year-old phone and I are not smart enough.

Instead of my phone, I thought I could use my credit card. However, credit cards issued by foreign banks are accepted only by a limited number of mainland retailers and service providers. So I ditched the plastic for paper, thinking no one could say no to cold, hard cash. To my surprise, many did. Taxi drivers, small shops and even restaurants refused cash payments, usually citing insufficient small change. If a shop or restaurant can’t break a 100-yuan banknote, should it even be in business?

This relentless pursuit of cashless convenience should not come at the exclusion of other forms of payment, at least, not yet. Consumers may not wish to use e-payment platforms, or like me, they might not be able to. Besides, what if there is a serious technical glitch that incapacitates smartphones, scanners and payment terminals? Please don’t think I am a Luddite. WeChat Pay and Alipay are brilliant for those who can use them, offering speedier transactions and lighter wallets.

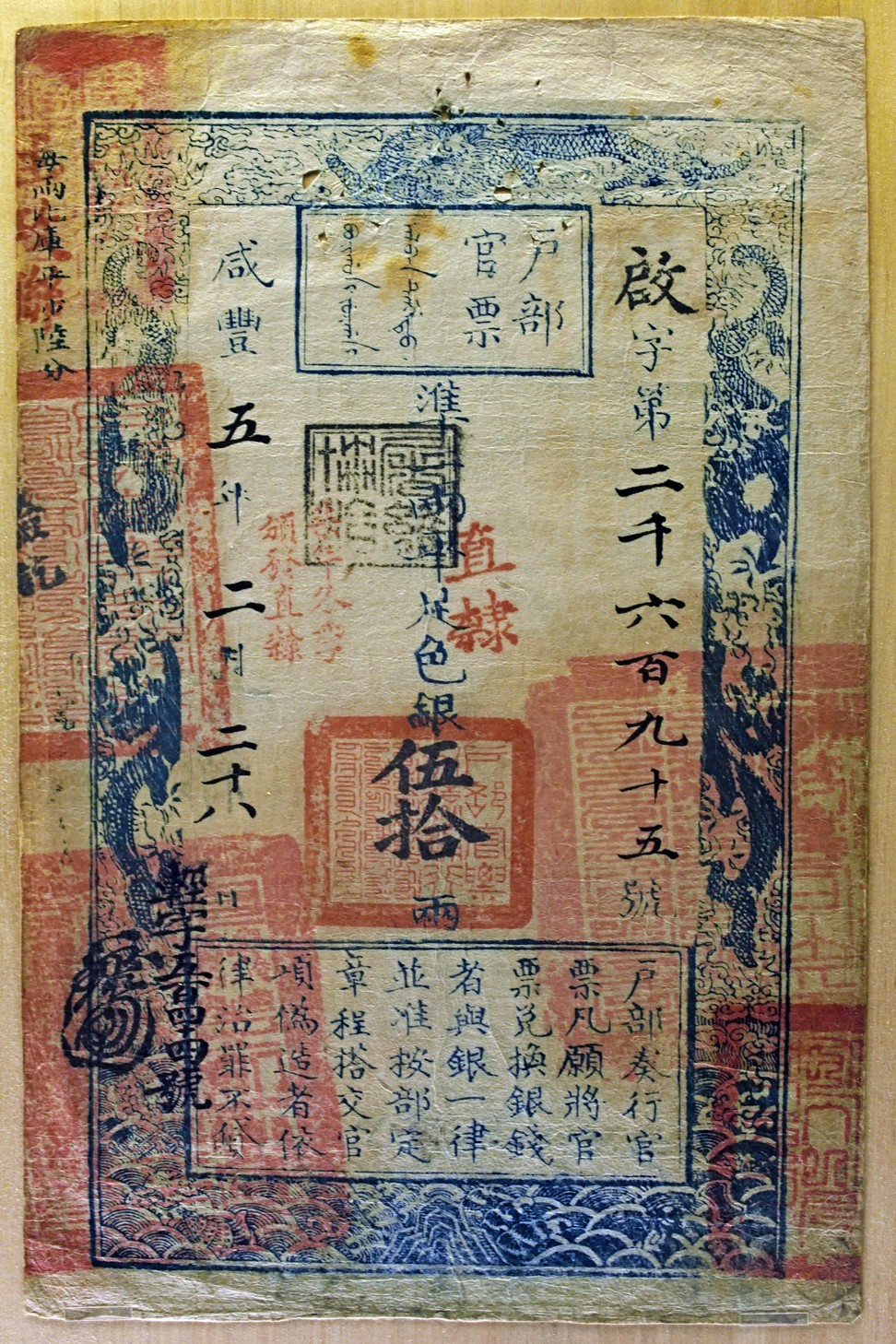

It was with lighter loads in mind that the first paper money was invented. Coins in various shapes, sizes and metals have been in existence since ancient times. At the beginning of the imperial era, however, the Qin dynasty’s first emperor (221-206BC) made round copper coins with a square hole in the centre the standard currency throughout the empire, and they remained so until the early 20th century.

The coins had a low face value, and large transactions required a massive quantity – literally a heavy burden for itinerant merchants who had to travel long distances with their goods. To mitigate this inconvenience, a money exchange system involving promissory notes developed in the early ninth century, during the Tang dynasty.

Aptly called feiqian (“flying money”), a merchant in the capital would deposit a quantity of coins with the metropolitan office of an army unit or government department, which issued him with a receipt. Instead of unwieldy cartloads of coins, the merchant carried this receipt to his destination where the unit’s local office exchanged it for the same quantity of coins he had deposited in the capital. Sometimes, instead of state organs, merchants would entrust their money to wealthy families with economic interests across the country.

In time, merchants began to trade directly with “flying money”, giving rise to an embryonic form of paper money. However, it wasn’t until some 200 years later, during the Northern Song dynasty, that “true” banknotes called jiaozi began to circulate, in Sichuan province.

Electronic payments, the latest in a series of historical innovations in the evolution of money, will probably replace banknotes and coins in the future. But for now, I still like the feel of paper and metal, and their anonymity.