With M+ museum collecting Hong Kong graffiti and neon art, we trace the roots of those words

- The ‘King of Kowloon’ was writing protest graffiti in Hong Kong before modern US graffiti emerged in the 1960s

- The city was also famous for neon signs, which have mostly disappeared, and both art forms are preserved at the newly opened M+ museum of visual culture

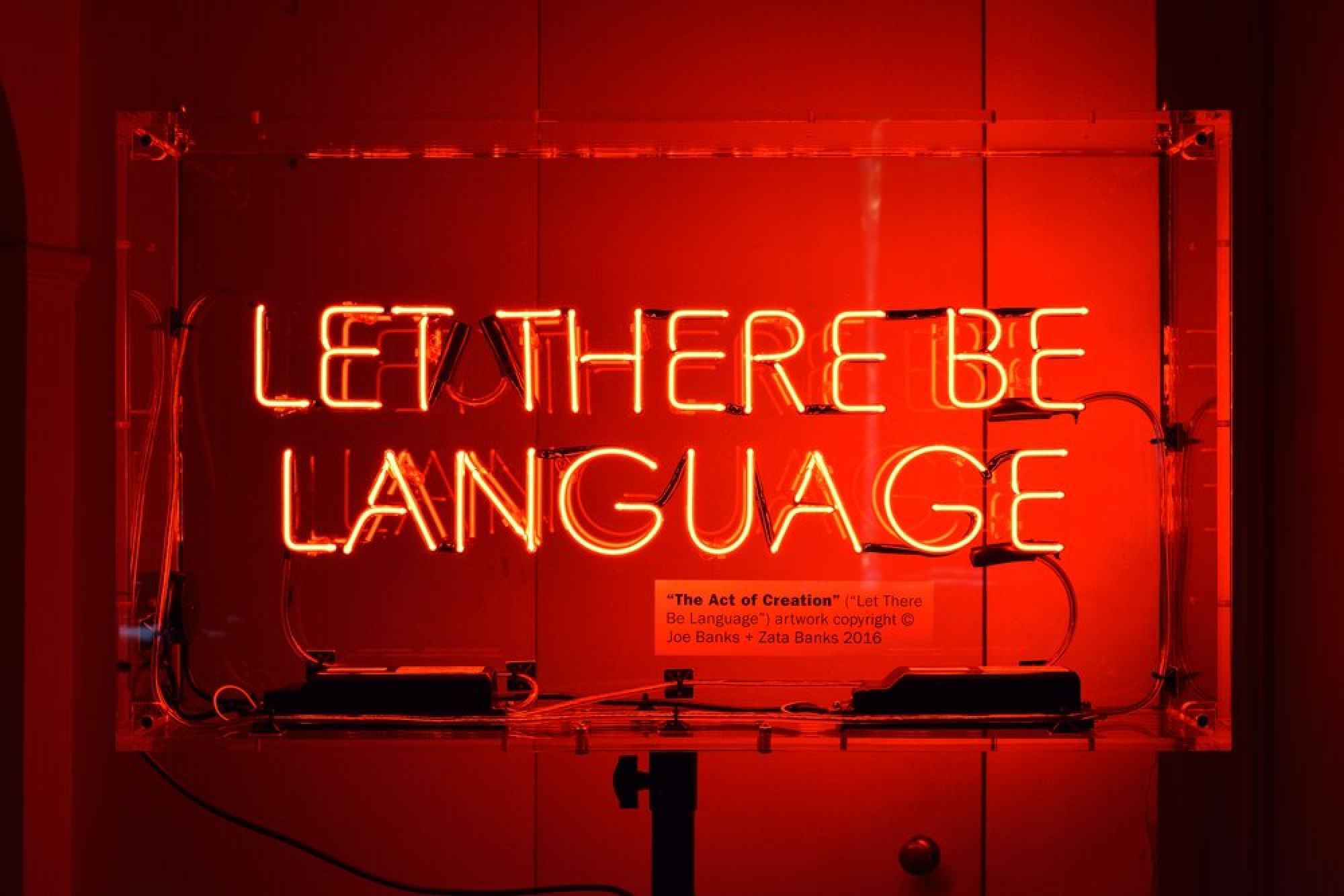

“Let there be language” proclaims the award-winning 2016 neon artwork The Act of Creation, by Joe and Zata Banks. Indeed, there is much language to be pondered in modern visual culture, typically in graffiti and neon art.

Graffiti – plural of graffito, from the Italian graffio, meaning “a scratch” – originally referred to drawings or writings scratched on walls and surfaces, seen on ancient walls in Pompeii and Rome. Only in the 1960s did graffiti come to be used for words or images marked (usually illegally) in public places, such as the modern urban graffiti that first appeared in Philadelphia and on New York subway trains.

Graffiti is widely studied as a vehicle for creating and contesting meanings, especially in articulating resistance to dominant powers.

Neon, from Greek νέον, “new”, was the name given by British chemists to the gas they isolated in 1898. When trapped in glass tubes and electrified, it lit up, giving us neon lighting, initially for commercial advertising then as an artistic medium. Text-based neon art burgeoned from the 1960s in philosophical or playful explorations of language and meaning.

Before ‘King of Kowloon’ Hong Kong barely had any graffiti. Look at it now

Other work – such as Joi T. Arcand’s ēkawiya nepēwisi (2019), “don’t be shy” in Cree, representing the Plains Cree glyph system in neon – speaks to issues of revitalising and promoting indigenous languages in contemporary public spaces.

Hong Kong’s once ubiquitous neon signs are a striking contemporary adaptation of the Chinese tradition of integrating calligraphy into architecture, typically as vertically arranged couplets and horizontal banners adorning entranceways and interiors.

Although Hong Kong’s neon is fast disappearing, several artefacts and more than 4,000 images now in M+’s permanent and online collections preserve and illuminate this visual urban vernacular of Hong Kong’s heritage.