How museums – at first private, later public – spread in Asia and the man who lent them impetus in Hong Kong

- Public cultural facilities grew with advances in literacy. At first they were private, such as White Rajah Charles Brooke’s Sarawak Museum, and then municipal

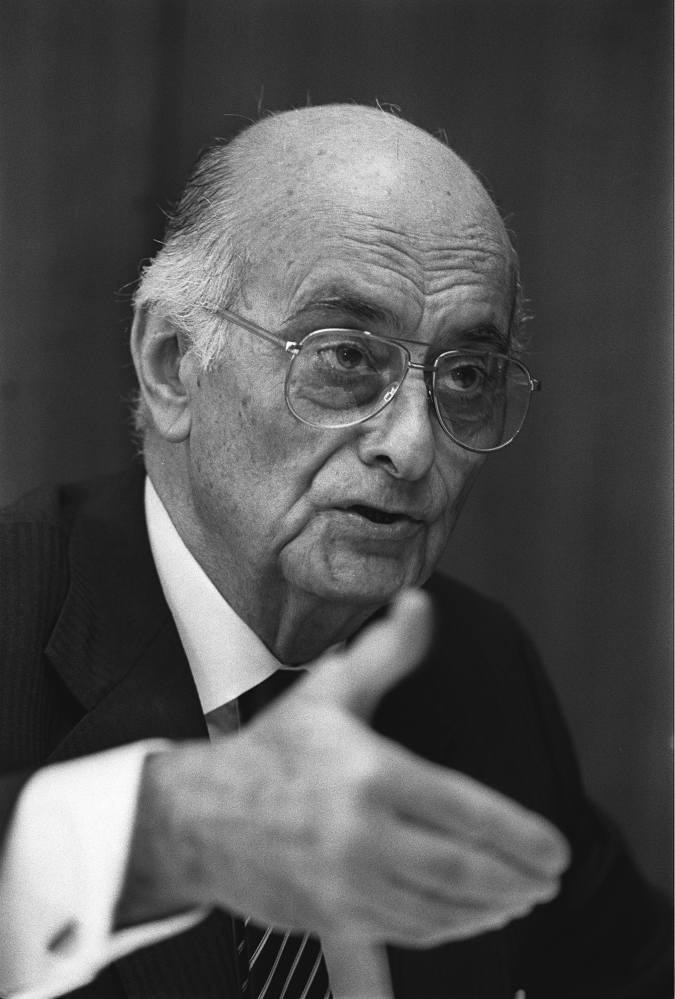

- In Hong Kong, the Urban Council’s Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales had a big hand in their rise; today Hongkongers can experience the world without leaving Kowloon

Wide-ranging notions of civic uplift spread throughout the 19th century world, in part driven by Enlightenment beliefs in the inevitability of human progress. (The intellectual movement that grew in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries emphasises science and logic over tradition and religion.)

There was also a recognition that commitment to the gradual “raising up” of populations – rather than their steady “levelling down” – was the best way to ensure long-term social stability and technological, economic and cultural advances.

One painfully important lesson had been learned from the political upheavals that gripped Europe after the French Revolution that began in 1789: wide chasms of socio-economic disparity inevitably generate violent social unrest.

Along with improved civic amenities, such as better water supplies, sewers, drains and transport links, the life of the mind was enhanced.

Advances in public education – it was, after all, inherently better to be literate – led to the improved provision of a wide range of public cultural facilities, such as libraries, orchestras and museums.

Private museums – also periodically opened to the public – led the way. These were often personal curations gathered by a wealthy individual during their travels and reflected their enthusiasms and specialisations; the Wallace Collection, in London, is a superb example. Some museums reflected the growing Enlightenment interest in the natural world and were “living collections” of rare plants and animals from far away.

Exhibits typified period tastes: glass cases filled with stuffed animals, shells and fossils; ethnological displays and local archaeological finds; a reference library; and a selection of uncontroversial artworks. All very “improving”, in the late Victorian manner, if somewhat musty, dusty and predictable.

By the 1970s, Hong Kong had an entire government sector for museums and related recreational facilities, driven initially by the immediate post-war spirit of change. Residents of various ethnicities had been thrown together by war and internment, or resistance activities in other places, notably in the interior of China.

After the waste and destruction of war, a general sense that “something better for everyone” should be created and sustained was channelled into numerous community initiatives, including new and expanded museums, orchestras, study circles, sports facilities and other cultural provisions.

As with many civic improvement initiatives in Hong Kong in those years, a key figure was Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales, the long-serving chairman of the (now defunct) Urban Council. As well as new and expanded cultural and sporting facilities, further employment opportunities opened up for local graduates in history, anthropology and other disciplines who did not wish to pursue careers in secondary or higher education.

Like much else in Hong Kong, with content selection left to career bureaucrats rather than genuine creatives, locally curated museum exhibitions can be rather formulaic compared with leading institutions elsewhere. But let the critics carp; the general public were happy enough with what was on offer: a welcome chance to educate, amuse and entertain themselves and their families, cooled by abundant air conditioning, for a token sum.

Superb thematic exhibitions, regularly borrowed from the world’s great museums, allow those without the means to travel to experience those places without ever leaving Kowloon.