The Christian converts in Ming dynasty China who made the religion respectable there and the millions of Chinese who will celebrate Christmas

- Christianity took proper root in China thanks to 16th century Jesuit missionaries. Among their influential converts was a minister of the Ming emperor’s court

- Today, at least 44 million Chinese Christians in China and millions more elsewhere celebrate Christmas, or the Festival of the Holy Birth

Christmas is fast approaching and as we plan for the festivities, let’s not forget what Christmas is about.

I used to be a Christian but presently I’d describe myself as agnostic. My Christian journey in my teens was brief but intense. I went to church more often than necessary, I proselytised, and I read the Bible daily as well as any book on Christianity that I could get my hands on.

Perhaps it was the latter that unravelled my faith. The careful reading of these books, the Bible included, convinced me that the irrationality and contradictions within the religion required a huge and unquestioning leap of faith from its adherents, a leap that I was not ready to take.

The Christian religion, in the form of Nestorian Christianity, arrived in China in the early 7th century, but the nascent church practically died out there because of natural attrition and sporadic persecution. It was almost a thousand years later, in the Ming dynasty, that the Roman Catholic Church, riding on the wave of the European age of exploration, laid the foundation of Christianity in modern China.

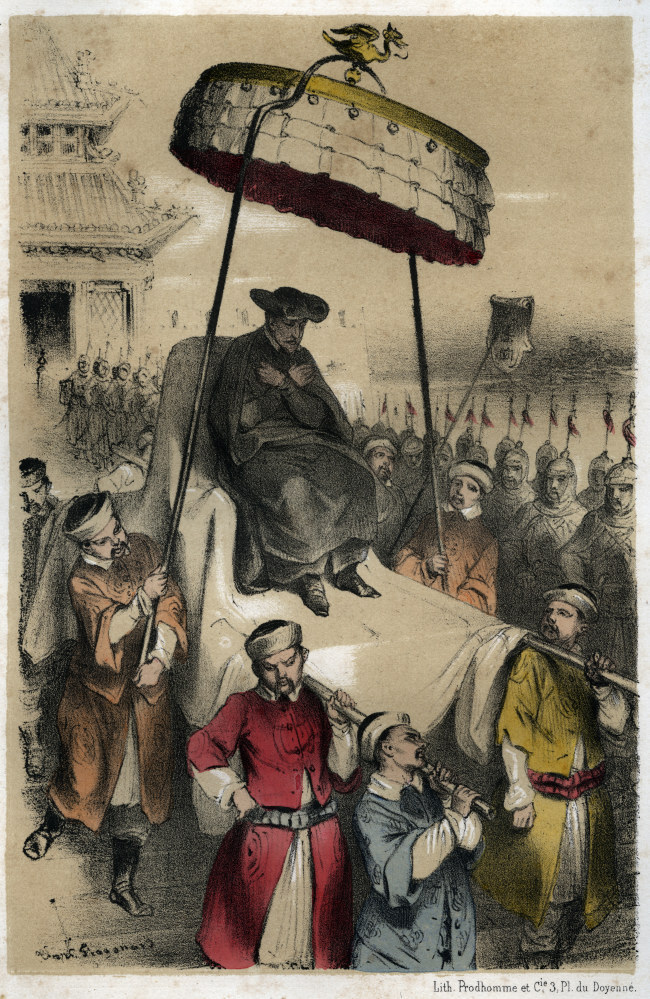

The four Chinese Christians with the highest profiles in the late Ming dynasty were Xu Guangqi (1562–1633), Li Zhizao (1571–1630), Yang Tingjun (1562–1627) and Wang Zheng (1571–1644). Among them, Xu Guangqi was the most prominent. In government, he rose to the position of Minister of Rites and concurrently Grand Secretary of the Wenyuan Hall in the Imperial Palace, a position of great power and prestige.

Apart from his erudition in Chinese classical studies, as well as in the more practical fields of astronomy, mathematics, and the agricultural and military sciences, he was also an avid student and translator of European scientific writings. Shanghai’s famous Xujiahui area is named after him.

While Western scientific knowledge was a major attraction for these Chinese intellectuals who converted to Christianity, their Christian faith was quite genuine if their post-conversion struggles were anything to go by.

At the age of 51, Wang Zheng was pressured by his family to take a 15-year-old concubine because he and his wife had no surviving sons. Tortured by guilt for this unchristian act of polygamy, he resolved not to have conjugal relations with his concubine for the rest of his life. He eventually resolved the issue of male heirs by adopting his nephews as his own sons.

Xu, Wang and others like them gave Christianity a stamp of respectability in China at the time. It wasn’t just a foreign curiosity that appealed to the uneducated and common, but a rigorous belief system – or as rigorous as any religion could be – that was embraced by members of the intellectual and social elite.

Christianity is the fastest growing religion in China today. Official figures put its adherents at 44 million but the number is probably much higher. Many of the 50 million members of ethnic Chinese communities outside China are also Christians. Together with their fellow co-religionists around the world, they will celebrate the Festival of the Holy Birth (shengdan jie) on the 25th of this month.