Then & Now | How to make sense of history when memories of an event differ subtly? Escape of Hong Kong POWs with help of a violinist is a case in point

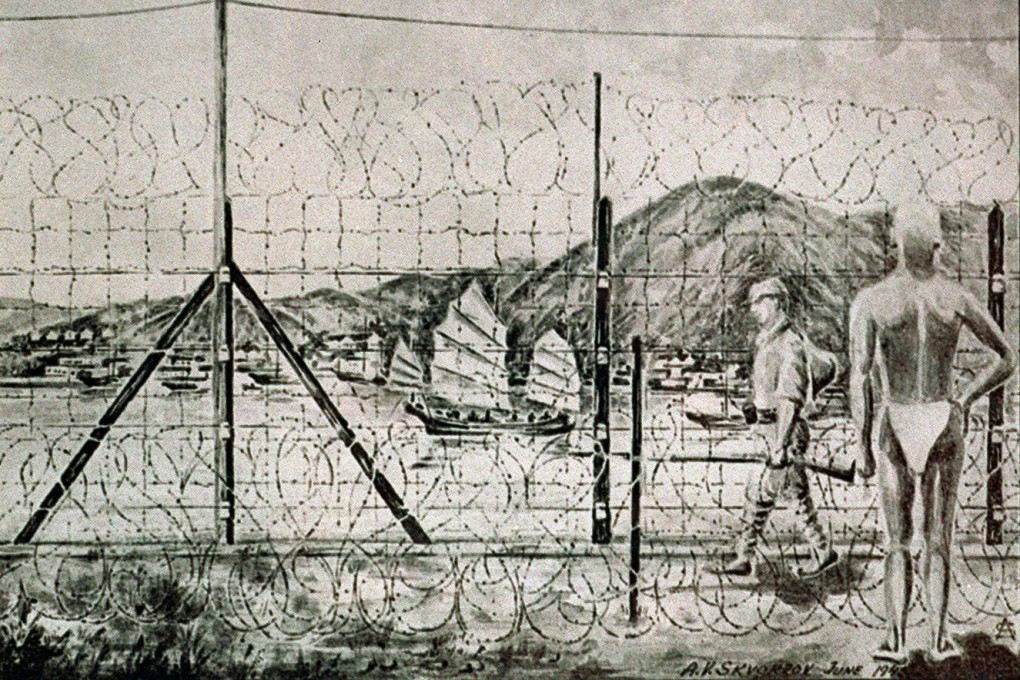

- During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, four soldiers escaped from the Sham Shui Po prisoner of war camp, helped by a violinist who played musical warnings

- The differing memories of participants highlight the challenges posed to historians when dealing with oral accounts of something that happened long ago

Competing versions of the past are perennial working challenges for historical researchers. Minor-but-telling accounts must be carefully sifted through until the most accurate possible version of “what happened” emerges. If that proves impossible, various versions must coexist, with appropriate cautions for each.

When personal testimony is involved, the process becomes additionally difficult. Oral accounts are often related many years after the events described. Memory fades over time, and a natural desire to believe that personal testimony must be completely right – after all, the individual telling the story was actually there – also comes into play.

But what occurs when specific remembered details are all materially the same, yet slightly different in emphasis or sequence? Some versions may have “improved in the telling” over the years, as any good anecdote has a tendency to do, and in due course, become “true” to the people telling them.

No deliberately invented falsehood exists; everything actually happened, just a bit differently to each participant. An amusing minor example of this conundrum revealed itself during a project that was researched long ago.