‘The celebrated aviary of Mr Beale’: how a Macau-based 19th century merchant and amateur naturalist set up maritime Asia’s premier private zoo

- 19th century merchant Thomas Beale poured some of his fortune into making a botanical and zoological garden in Macau that was the envy of many naturalists

- The amateur collector’s aviary notably housed some spectacular birds of paradise, which European naturalists had thought to be mythological, not having seen any

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, scholarly interest in the natural world rapidly expanded.

Academic generalists – often protégés of renowned scientists such as Joseph Banks – were attached to trading missions that travelled everywhere from Brazil to the Philippines.

With personal interests and accumulated knowledge that ranged from botany and ornithology to ethnology and archaeology, their sheer exuberant delight often rubbed off on those with whom they came into contact.

With few other intellectual outlets to engage them, ample financial resources and a broad range of regional contacts to leverage, some businessmen became renowned amateur naturalists and collectors in their own right.

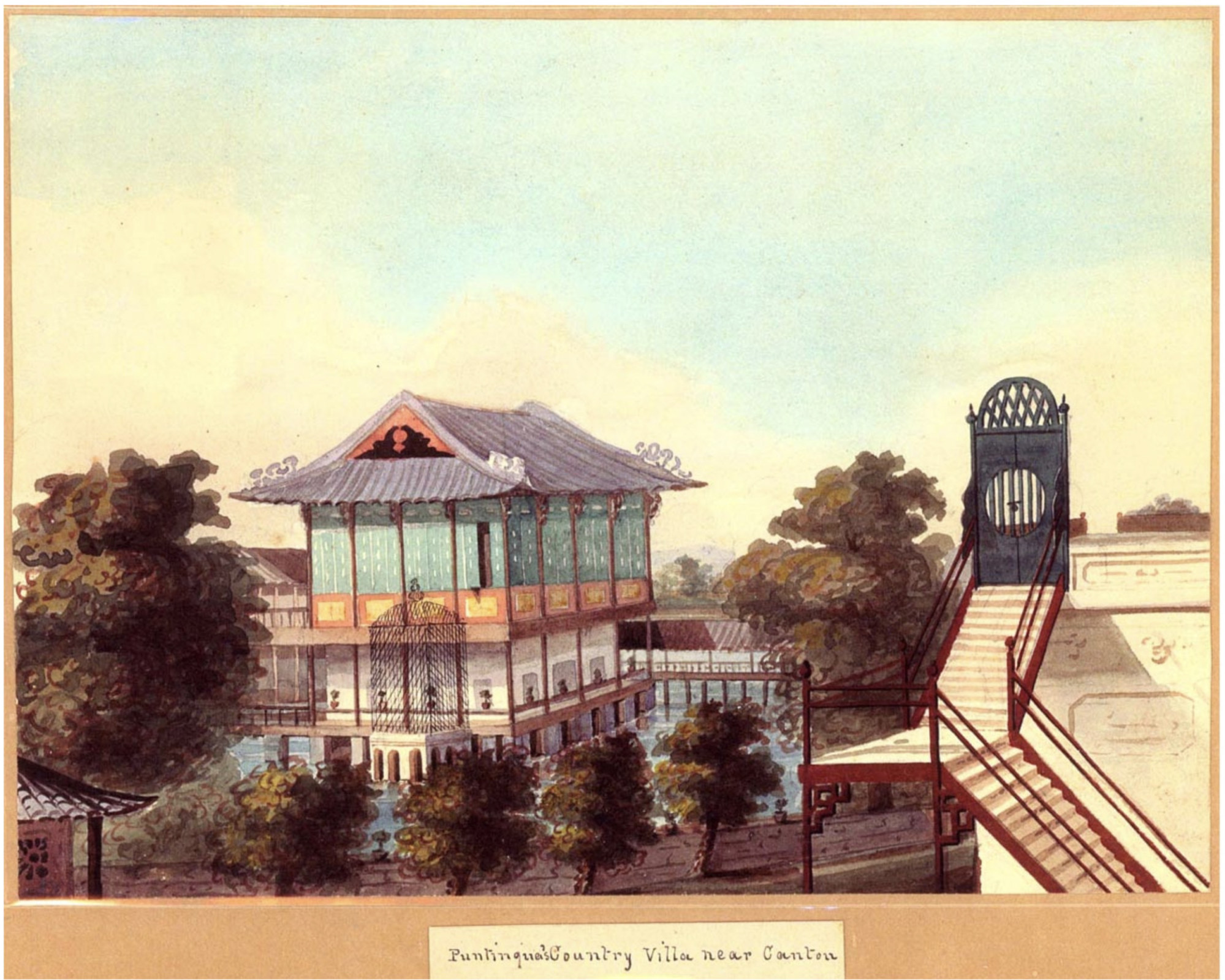

Unlikely as this may appear today, maritime Asia’s premier private botanical and zoological garden – in reality, the passionate hobby of a wealthy British trader – was located in the tiny Portuguese settlement of Macau.

A Chinese scholar who showed colleagues Hong Kong wasn’t full of philistines

Born in poverty around 1775 – no exact birth record exists – Thomas Beale came to Asia as a young man, and eventually settled in Macau. Like countless others before and since, Beale’s spectacular wealth was accumulated through hard-edged mercantile shrewdness, allied to a “winner-takes-all” capacity for extraordinary financial risk.

Aided by his extensive networks, Beale constantly sourced additions for his botanical and ornithological collections.

A vast aviary 12 metres (40ft) long and six metres high – sizeable even by today’s standards – housed about 600 birds. Everything from Java sparrows and Reeves’ pheasants to Indian hill mynahs and Moluccan cockatoos was represented in the aviary, or in cages hung up around the garden and grounds.

Beale’s most celebrated avian treasures were several birds of paradise. Found only in the eastern Moluccas and New Guinea, and long dismissed as mythological by European naturalists who had never observed one in the wild, numerous credible witnesses were finally able to report back – through first-hand observation – that these spectacular tropical birds really did exist.

In Sketches of China: With Illustrations from Original Drawings (1830), William Wightman Wood also noted the famed bird of paradise. “A splendid living specimen is in the possession of Mr. Beale [and is] almost domesticated.

“It feeds from the hand of its amiable owner without fear, and appears capable of being rendered perfectly tame and familiar. This is perhaps the only specimen at present existing in confinement.”

Around the same time, Edmund Roberts noted in Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam and Muscat During The Years 1832-3-4 (1837) that he “had the pleasure of seeing the celebrated aviary of Mr. Beale”.

Like Manchester and cotton, Hong Kong is built on the opium trade’s profits

Nevertheless, he lived on quietly until 1841, when – in an apparent suicide – his body washed up on the beach at Cacilhas. A simple tomb in the Old Protestant Cemetery is Beale’s only permanent memorial in Macau; sadly, nothing remains of that once-renowned garden.