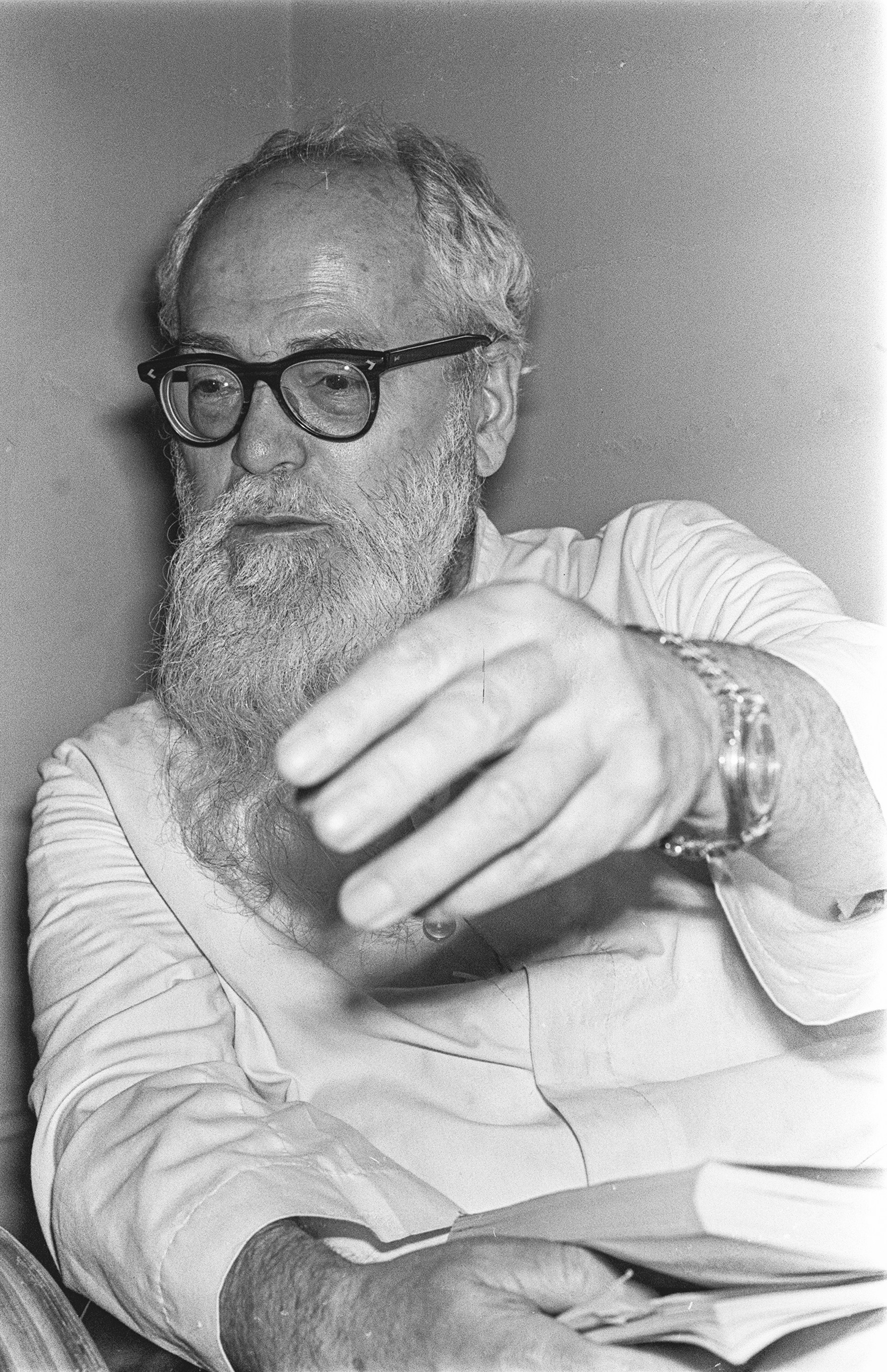

The Portuguese amateur historian of Hong Kong and Macau, José Maria ‘Jack’ Braga, whose work still resonates 35 years after his death

- Hong Kong-born Portuguese scholar José Maria ‘Jack’ Braga was among a group of amateur historians who dug up a mine of information for future generations

- He and his father wrote a noted history of Portuguese settlement in Hong Kong and Macau, and he befriended fellow amateur historians such as Austin Coates

Since Hong Kong’s mid-19th century urban beginnings, quiet, painstaking independent research work undertaken by a wide range of amateur local scholars – all drawn from a variety of ethnic backgrounds – has resulted in extraordinary resource sets from which others have benefited.

Creation of archival material for the future was, however, not their original intention. Private study, by and large, was undertaken to help satisfy individual subject interests; a desire for some form of wealth, renown or career advancement was seldom a motivation.

Along the way, the steady spadework that resulted from their various distractions and digressions unearthed unexpected riches for others to utilise.

Beneficiaries have ranged from professional academic scholars, who transformed collations of raw primary source data into more detailed, wide-ranging research articles, to general authors who then used their own distinctive writing and storytelling skills to produce popular-orientated historical works based on the findings of others.

The amateur social historian all Hong Kong scholars owe a big debt to

One such individual, whose decades of quiet burrowing benefited – and continues to benefit – a variety of other writers was Hong Kong-born José Maria “Jack” Braga (1897-1988).

Why we have amateur historians to thank for understanding of Hong Kong

A youthful financial indiscretion that involved losses to the Union Insurance Society of Canton saw him briefly jailed in Hong Kong. In disgrace, he went to Macau to lead a quiet life, and worked as a teacher at St Joseph’s Seminary from 1924 to 1946.

During these “wilderness years” Braga’s distinct skill sets bequeathed by his personal heritage, and the ways in which they complemented each other became apparent to him.

Burgeoning interest in the centuries-old Portuguese history across Asia expanded with personal access to immediately available archival material – much of which was lodged within the same institution as his “day job” – or else very close by.

Over the next few decades, he developed close personal friendships with other independent scholars whose different-yet-connected research interests cross-fertilised each other.

Like hundreds of other local Portuguese, J.P. Braga decamped to neutral Macau in 1942 from Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. Father and son – long-since reconciled – collaborated on various historical writing and research projects until the former’s death in 1944; their most extensive – The Portuguese in Hongkong and China: Their Beginning, Settlement and Progress during One Hundred Years (1944) – remains a standard reference work.

Pleasantly archaic, Jack Braga’s personal writing style befitted someone whose inner world concerned earlier times and places, and the disparate personalities who inhabited them.

He also saw Boxer’s remarkable early work Macau Three Hundred Years Ago (1942) through to publication – no mean feat, with the author a prisoner of war in Hong Kong and a critical local shortage of paper.

As the financial uncertainties of old age approached, Braga sought a permanent home for his extraordinary private research collection, which numbered around 7,400 books, pamphlets and other materials in English and Portuguese, along with about 160 paintings, prints, lithographs, drawings and sketches.

Originally offered to the University of Hong Kong, through his friendship with then-librarian Geoffrey Bonsall, unfortunate institutional shortsightedness (and shortage of funds) saw the Braga Collection – as it became known – sold in 1966 to the National Library of Australia.

After working in Canberra for some years, as part of the sale conditions, Braga eventually moved to San Francisco, where he died in 1988.