Once the oldest known monument in Hong Kong, Sung Wong Toi has survived development plans and Japanese occupiers’ quarrying

- Inscribed stone dating from the Southern Song dynasty and the time of boy-emperor Duanzong’s flight through the Kowloon hills is in its own park in Kowloon City

- The first antiquity gazetted for historical preservation in Hong Kong, it was part of a large boulder atop a hill until Japanese occupiers quarried the latter

Hong Kong contains few significant heritage locations with historical relics that date back more than a couple of centuries – at the very oldest. Reasons for this absence are obvious, if rarely stated – especially these days.

Ultimately, urban Hong Kong is an artefact of the mid-19th century British presence on the China coast, which – along with foreign rule – generated rapid, steady population flows into what were hitherto a series of scattered, semi-subsistence-level villages geographically isolated from larger urban centres.

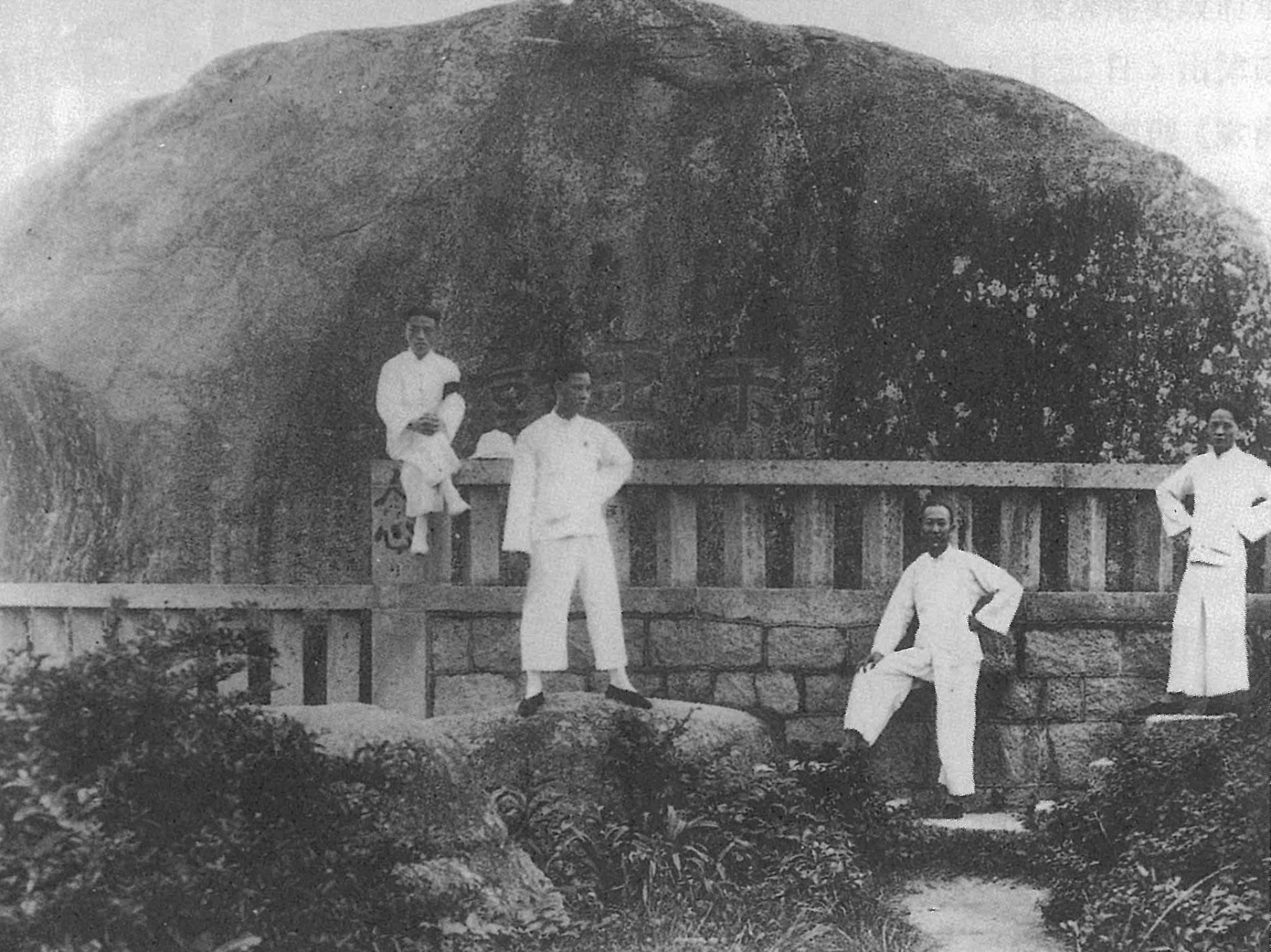

Hong Kong’s oldest documented historical monument lurks quietly in an attractive small park in Kowloon City. Sung Wong Toi – “Sung Emperor’s Terrace” – was justifiably regarded, before the Pacific war supervened, as the single most important Chinese antiquity found in Hong Kong.

The stone carving is a tangible link to the final years of the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), and second-to-last boy-emperor Duanzong’s escape through the Kowloon hills from invading Mongol hordes.

Present-day memorial inscriptions were carved in 1807; earlier incisions on the boulder had been recorded down the centuries – the first dated from sometime in the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

In 1898, the second Convention of Peking was signed between Britain and China, which brought what became the New Territories under British administration under a 99-year lease; early genesis of Hong Kong’s later “1997 issue”.

After a swiftly suppressed villager-led uprising in the New Territories the following year – locally known as the Six-Day War, which was centred on Tai Po, Lam Tsuen and Kam Tin, the Chinese magistrate at Kowloon City was withdrawn, and never subsequently replaced.

The restored magistracy buildings now form a centrepiece of Kowloon Walled City Park, one of urban Hong Kong’s most pleasantly unexpected civic spaces.

Despite conservation status, the Hong Kong government attempted to quietly sell the surrounding land for redevelopment in 1915; this plan was revealed to the public by Li Sui-kum, an example of one of Hong Kong’s rarest species – a heritage-minded building contractor.

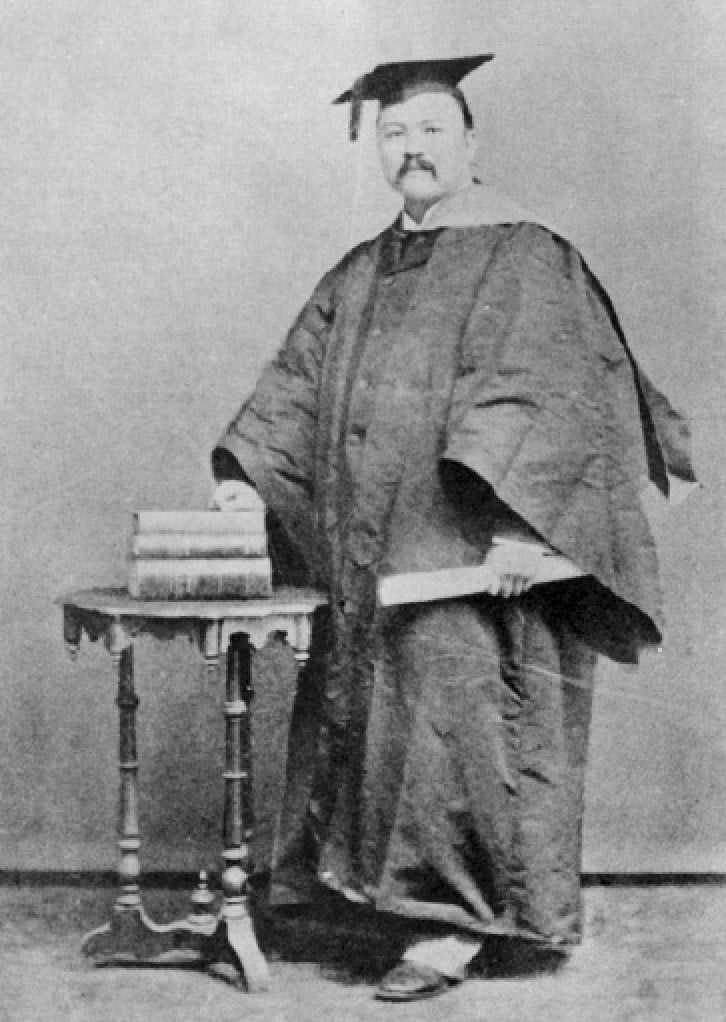

Thus alerted, University of Hong Kong vice-chancellor Sir Charles Eliot and prominent academic Lai Chai-hei petitioned Governor Sir Henry May for the stone’s retention, and to ensure better long-range conservation on historical grounds.

Development plans were subsequently abandoned, and Li later personally donated substantial funds for Chinese-style gardens, paved paths and scenic viewing pavilions to be built around the site.

Five Hong Kong parks, for walks amid Kowloon’s urban jungle

By the late 1920s, Sung Wong Toi had become one of Kowloon’s more popular tourist spots; little mentioned in Western guidebooks from the period, the complex appealed to visitors from mainland China and elsewhere in the overseas diaspora.

In 1943, during the Japanese occupation, extensions to Kai Tak airport’s runway saw most of the 114-foot-high (35-metre-high) Sung Wong Toi Hill quarried for landfill; Kowloon Walled City also lost its stone walls at this time.

While the boulder was split apart and broken up, the inscribed section was preserved intact and kept in storage.

Sung Wong Toi Park was opened in 1959. This reinstated monument, set in well-maintained grounds, provides a rare corner of tranquillity in Kowloon City, and has experienced a resurgence of popularity with mainland visitors.

Admission is free and, as a bonus since Kai Tak airport’s closure in 1998, there is no longer a constant stream of aircraft thundering down every few minutes, only a few metres overhead.