How shoddy building construction prompted Hong Kong’s love of glazed ceramic tiles

- By the end of the 1960s glazed ceramic tiles were a near-universal feature across Hong Kong buildings, and remain so today

- Contractors using salt water in concrete in the 50s and 60s led to widespread corrosion; ceramic tiles helped delay the onset of more serious structural issues

Construction methods, and forms of decorative and practical building finishes, have evolved over time in Hong Kong.

From the 1860s, early urban photography reveals exterior walls rendered in roughcast stucco, faced in early forms of Portland cement and ferroconcrete, or surfaced with red bricks of various provenances; while most came from elsewhere in China, some originated as ship’s ballast brought out from Britain.

Resultant aesthetic effects – especially when combined with plaster finishes – could be very pleasing. These decorative trends continued into the late 1940s, when Hong Kong’s enduring love affair with tiled exterior building surfaces began.

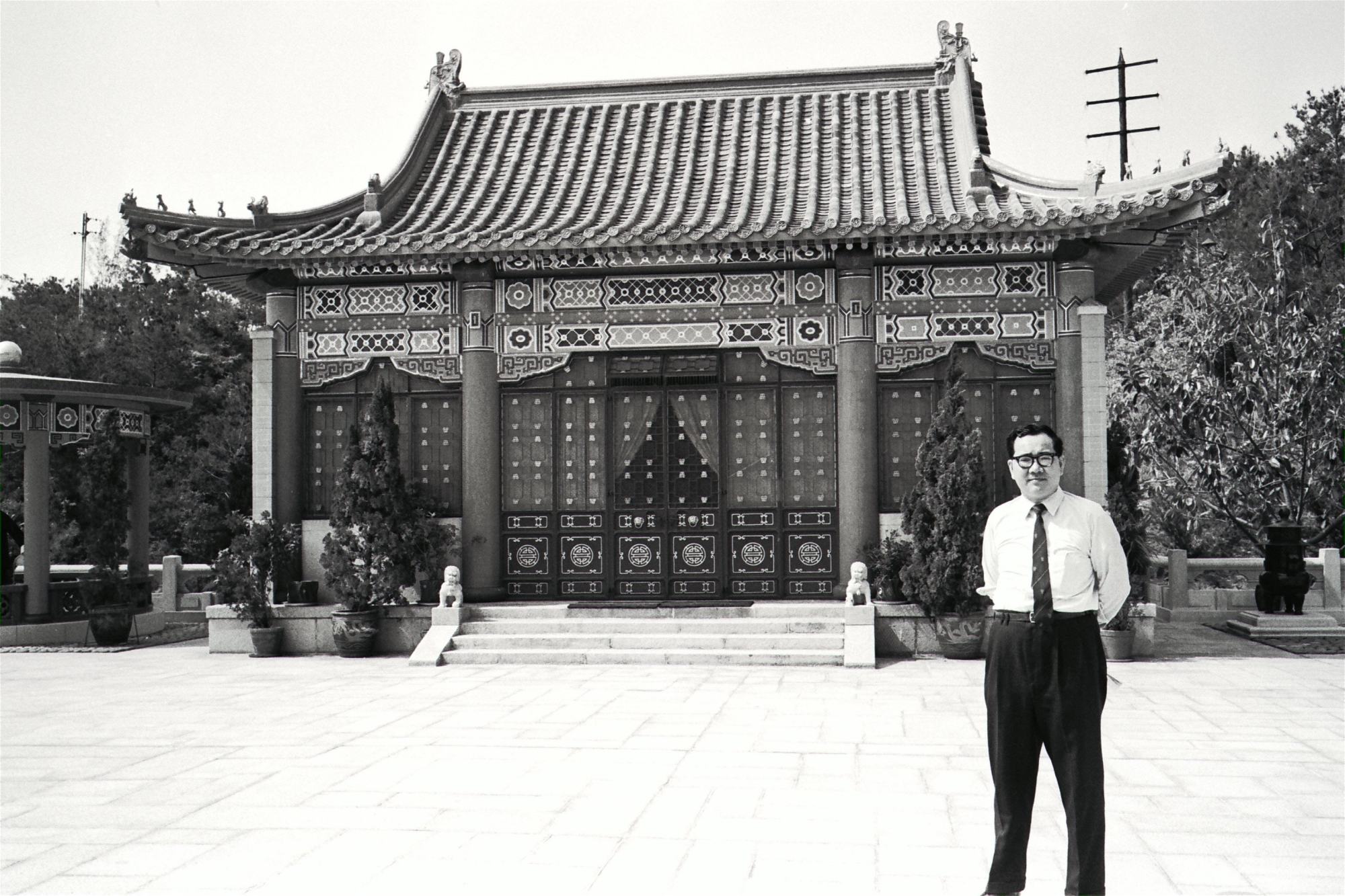

University of Hong Kong engineering graduate Lee Iu-cheung (1896-1976) was among the first to popularise the glazed ceramic tile trend.

A shrewd businessman, philanthropist and long-term Tung Wah Group of Hospitals committee member, Lee owned a number of local factories that produced glazed ceramic tiles, along with washbasins, pipes and other sanitary ware; for this reason, Lee was popularly nicknamed – in his lifetime – Hong Kong’s undisputed “Toilet King”.

Reasonably priced and practical, by the end of the 60s glazed ceramic tiles were a near-universal feature across Hong Kong buildings, and remain so today.

Chinese green-glazed ceramic tiles and decorative items make a comeback

Hong Kong experienced chronic freshwater shortages throughout the 50s and 60s, which meant that building contractors often used salt water in their mixtures of sand and concrete to help cut costs.

This disastrous combination inevitably led to eventual corrosion of reinforcing bars, with steadily rotting concrete, cracks and leakage starkly apparent within a few years.

Widespread official corruption – particularly among building inspectors – meant that by the time structural damage became obvious, units within the new building had long-since been sold and resold – possibly several times over.

These shoddy construction methods led to the widespread use of glazed ceramic tiles. Plastered over the exterior surface, these partially waterproofed substandard buildings and helped delay the onset of more serious structural problems.

From a purely decorative standpoint, glazed ceramic tiles ensure that a building never needs to be painted, either; one application usually lasts a couple of decades.

Effective, long-term building maintenance has seldom been a Hong Kong strongpoint; local preference for quick-fix, cheap-as-possible, one-time-only solutions is mirrored in the widespread deployment of glazed-tile exterior surfaces.

Proud Chinese people’s cultured tastes help revive furniture making craft

From these early practical beginnings, use of glazed ceramic tiles for exterior building purposes became universal by the 90s, and they could be found plastered on every conceivable surface; public buildings were as prone to these encrustations as private-sector developments.

Dust pink, for some reason, became a particular favourite hue; Tsim Sha Tsui’s Hong Kong Cultural Centre, Space Museum and Hong Kong Museum of History are all this particular shade.

Right across the New Territories, unsightly rashes of badly built, virtually unplanned village developments, which date from around the same period, have also been waterproofed with glazed ceramic tiles; curiously enough, dust pink is also a preferred shade.

When Hong Kong started to change into a concrete jungle in the 1950s

As village house developments continue unabated, it seems probable that the sale of glazed ceramic tiles for out-of-bathroom purposes will also continue well into the foreseeable future.

From 1949, Lee built the extensive Dragon Garden complex in Sham Tseng. Over the next 20 years, this imaginative Chinese pleasure ground, which spread out over several hectares, became a lesser-known New Territories counterpart to the better known (now sadly demolished) Tiger Balm Garden in Tai Hang, on Hong Kong Island.

Numerous examples of glazed ceramic tiles were used throughout the Dragon Garden, which was notably featured in the 1974 James Bond film The Man with the Golden Gun, as well as various locally produced movies.

In 2006, Lee’s heirs became embroiled in a family dispute over conflicting preservation priorities for the Dragon Garden. Subsequently spared from redevelopment, the sprawling complex, which contains more than 100 plant species and numerous mature Buddhist pine trees, is now periodically open to the public.