Karl Lagerfeld saved Chanel – so which other dormant heritage brands are being revived?

Giant luxury groups and Chinese investment firms are reviving European ‘sleeping beauties’ such as Jean Patou, Paul Poiret, and Gieves & Hawkes

Haute couture houses suffered during the first and second world wars from fabric limitations and financial instability. They lost their wealthiest American clients due to the Wall Street Crash in 1929. All those tragic events, combined with the ready-to-wear revolution, led to the disappearance of many famous names such as House of Worth, Paul Poiret, Jean Patou, Madeleine Vionnet, Molyneux, Schiaparelli, Rochas, Doucet and Nina Ricci.

Ailing, once glamorous fashion houses that require an injection of cash from a wealthy entrepreneur to save them from bankruptcy and oblivion are often referred to as “sleeping beauty” brands.

The late Karl Lagerfeld provided the best example of how to revive one of fashion’s “sleeping beauties” when he saved Chanel from oblivion in 1983 and turned it into a legendary luxury brand with revenues of US$9.62 billion for 2017.

Lagerfeld, who led the brand for 36 years,recalled, “Everybody said, ‘Don’t touch it, it’s dead, it will never come back.’ But I thought it was a challenge. Thirty-five years ago, old labels were old labels. Now everybody wants to revive a label.”

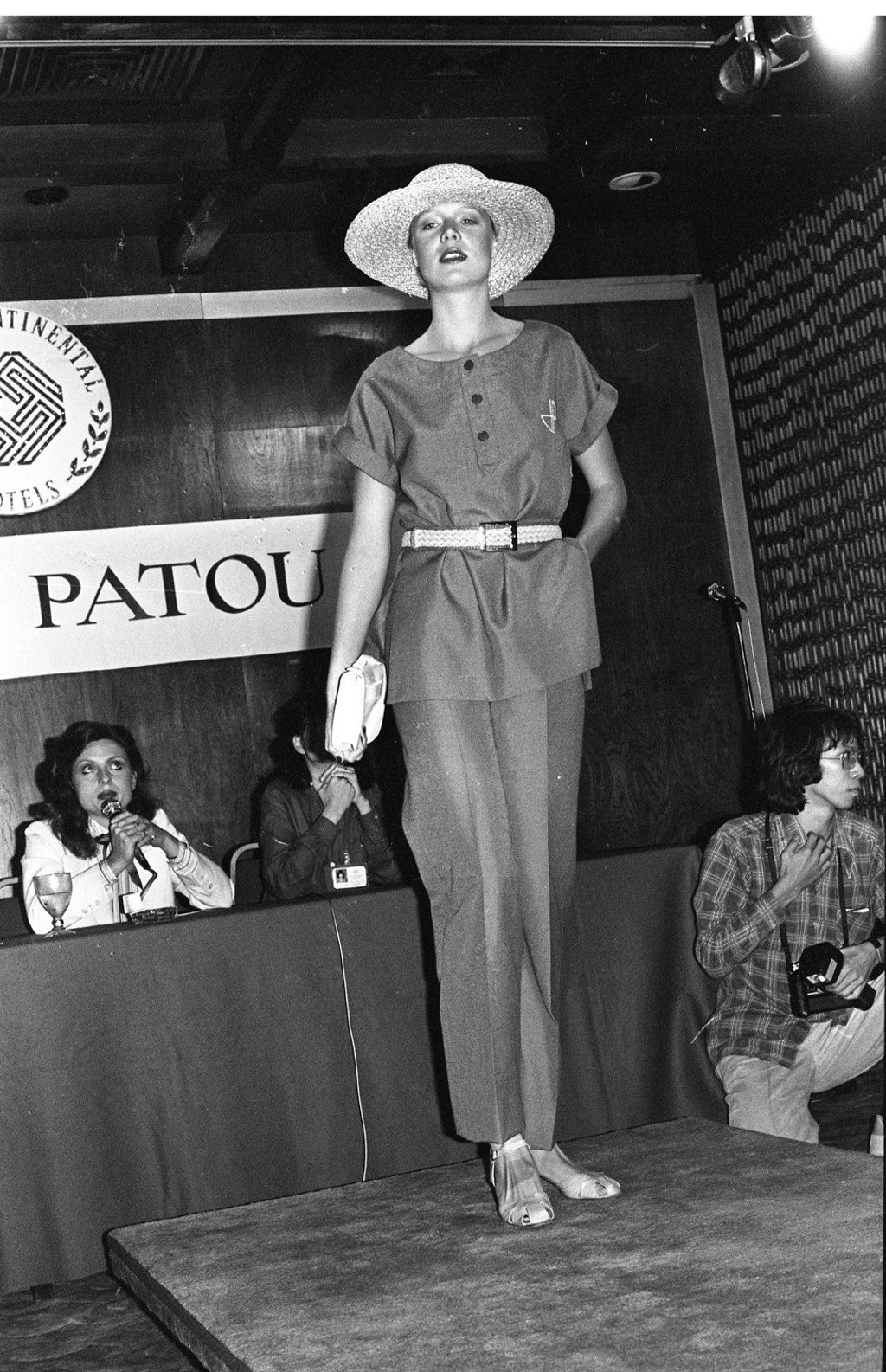

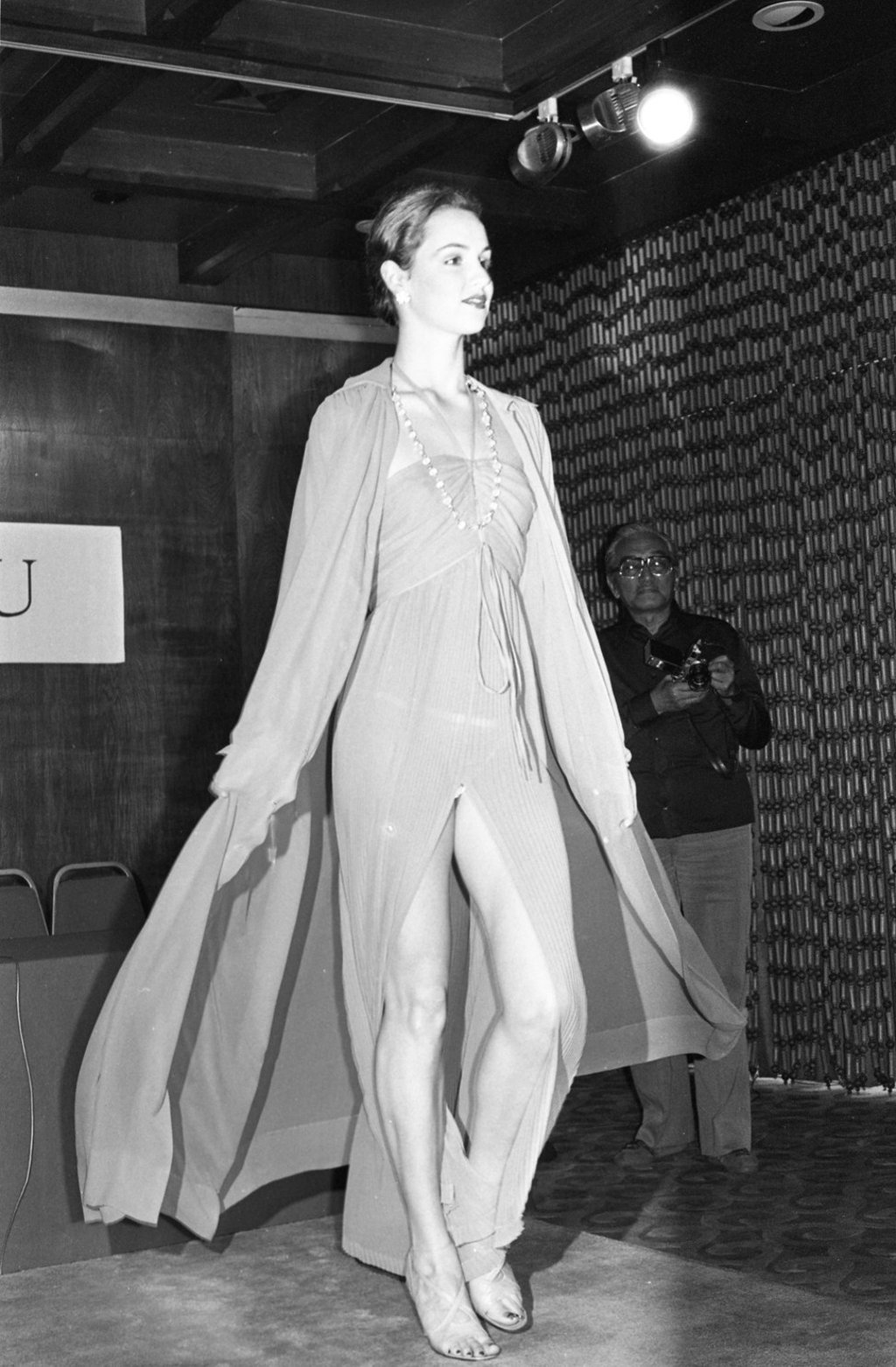

In September 2018, the LVMH group announced plans to relaunch the couture house Jean Patou, Chanel’s biggest rival after the first world war. Founded in the 1910s, Jean Patou was once a household name in fashion, popular for his chic silhouettes with comfortable style. The French couturier was also considered the godfather of sportswear. In 1921, French tennis diva Suzanne Lenglen caused a stir by wearing Jean Patou’s daring outfit at Wimbledon. Showing a brilliant business sense, Jean Patou also applied his own “JP” monogram to his sportswear designs that would become the first visible designer label in the world.