Why Westerners misinterpret modern Chinese art – and how perceptions can be changed

When West Kowloon’s M+ museum finally opens, perhaps towards the end of 2020, Uli Sigg hopes it will completely change the world’s idea of contemporary Chinese art. Sigg is a Swiss businessman, diplomat and art collector.

While around the world there have been several exhibitions of parts of his 2,500-piece collection – the world’s largest – Western curators have tended to choose items for display according to their own preconceptions about China. They have a particular penchant for the political, such as the period of pop art from the 80s and 90s, which deliberately took aim at Mao Zedong and his legacy.

“A Western curator will always prefer a work that has to do with human rights and not understand a work that deals in a patient way or even a spectacular way with calligraphy, because he doesn’t know [it],” says Sigg.

But there’s much more to contemporary Chinese art than politics, and the 1,510 works from his collection that will appear at M+ will paint a broader picture.

Sigg is at Vienna’s stately Austrian Museum of Applied Arts/Contemporary Art (MAK) for the opening of “Chinese Whispers”, a show of around 110 works from his collection. These are mostly items acquired since the 2012 donation to M+.

The show’s title may be cringingly obvious, but he believes it is entirely appropriate. It is a perfect metaphor for the gap between Chinese artists’ intentions and Western understanding.

“I see it here [in the West] with the curating. I read the wall texts they write and it’s something else than what the artist in the context aspired to do. So it’s a good metaphor because it’s a fact: something else comes out.”

To be fair, much Chinese art of the last few decades has seemed skilfully produced to appeal to the West’s preconceptions of China, treating the classical canon and the clichéd square-jawed worker-heroes of Soviet-influenced 20th-century propaganda alike as an image bank to be plundered at will.

Western art from Mantegna to Modigliani has also long been sampled. It is perhaps the combination of this intention to communicate with the viewer’s wallet and the use of a familiar visual vocabulary that means there’s very little about modern Chinese art that truly has the inscrutability Westerners are often predisposed to discover. The struggle to gain critical and commercial acceptance overseas has made the Chinese avant-garde accessible to anyone.

“Avant-garde” seems an entirely inappropriate term for an art mostly concerned with looking back rather than forward, that rarely finds any subject of discussion other than the Chinese condition, and whose comment even on that is often timid.

But Sigg asserts there has always been plenty of contemporary Chinese art that was not so self-consciously Chinese. It just was not the art chosen by foreign buyers or curators, and so the world remains largely unaware of it.

“There is a large group of Chinese artists that do not want to be seen as Chinese artists. They want to be seen as good artists, global artists. They hate even their passports. And they hate to be invited to a venue as a Chinese. They want to be invited for their art,” he says.

Many Chinese artists do not want to be seen as Chinese artists. They want to be seen as good artists, global artists

Sigg has often described his collection as a resource for studying China. But Chinese artists are involved in the same Faustian bargain as the rest of society, accepting limited economic freedoms in return for relinquishing political ones. Add to this self-censorship the conscious creation of what appeals to a Western view of China, and if the art provides a window into China in modern times, then surely it is through distorted glass. It must be a view of the art world, rather than of China itself.

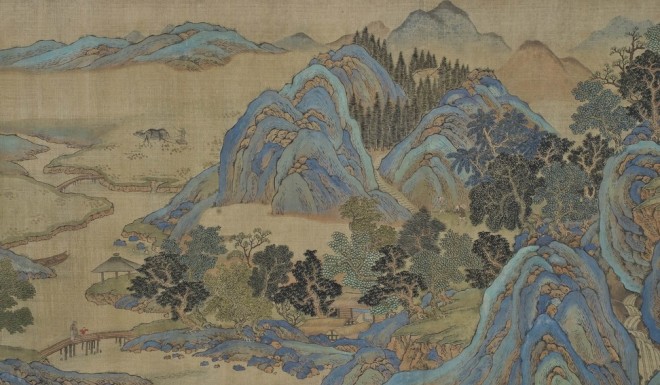

Large installations fill some of MAK’s high-ceilinged halls, and canvasses sprawl across their walls opposite delicate ceramics and other Chinese antiquities from the museum’s own collection.

MAK curator Bärbel Vischer is clear about what visitors will find surprising.

“I think [it’s] the density, and also the confrontation between the contemporary and the historical pieces,” she says. “The works are highly political.”

But it is the sheer scale and variety of the new work that is more likely to impress, and which shows that Sigg is right – there’s much that is not overtly political.

He Xiangyu’s The Tank Project – a full-size tank-shaped leather overcoat for a tank – has obvious political overtones, but as the artist remarks in the catalogue, that is not the point. The politics is “like a piece of vegetable in a burger”, he says. “It’s an option, but for my works, it’s not necessarily important and there are more levels.”

Feng Mengbo’s ink painting of mesmerisingly repeated Chinese characters, spanning an entire wall, is simply a meditation on which of them appear in a smartphone’s limited vocabulary, and on the perhaps uncertain future of those that do not.

And there is much that is not obviously Chinese, such as Shao Fan’s multilayered oil painting of a large rabbit, Chinese only in its title’s reference to the Chinese myth: Moon Rabbit.

But admittedly those paintings with their origins and commentary more clearly on display, such as Zhao Bandi’s “Scenery with Monitors”, depicting a CCTV-camera-festooned pole in a public park, have more immediate appeal.

“There are [Chinese] artists who want to come into this mainstream – the global mainstream, I call it – and not look distinctly anything,” says Sigg. “But I don’t know whether that’s the most interesting art in the end.”

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

Art collector Uli Sigg says Chinese artworks are often misinterpreted by the West