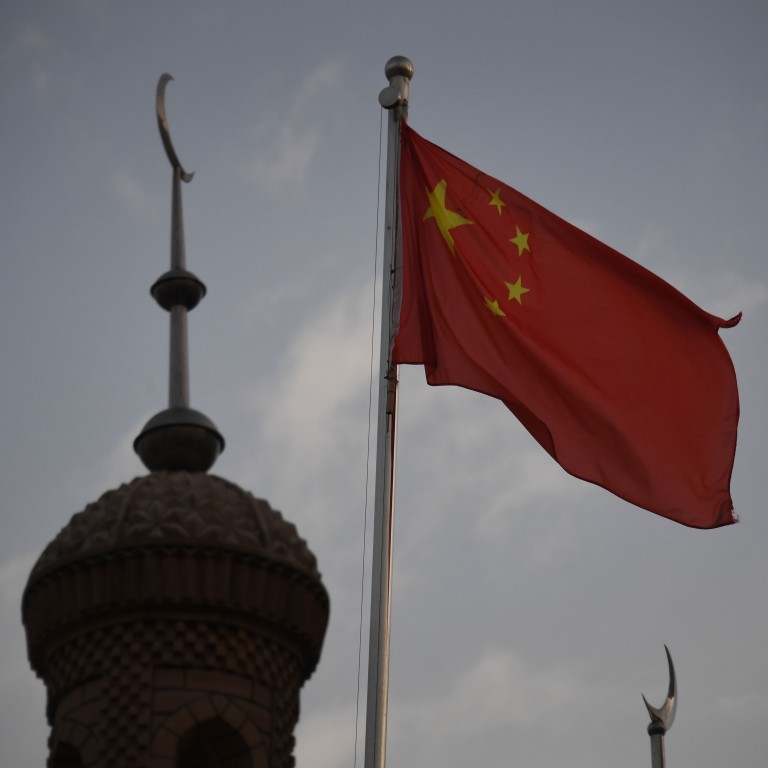

Why Indonesia’s muted response to China’s Xinjiang Uyghur internment camps is in stark contrast to anger over Rohingya crisis

- A new report by the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict says some Indonesians and Islamic groups see the reports of religious persecution as Western propaganda aimed at denigrating China

- The government of President Joko Widodo is also worried that taking a more vocal stance would embolden the country’s influential Islamic right

The report, published by the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict think tank on Thursday, quotes Dr Munajat Stain, a senior aide to President Joko Widodo as saying: “We did not want to engage in their [Uygur persecution] narrative because it would only empower the Islamists and radicals belonging to the opposition.”

US sanctions over Uygur internment camps are ‘ready to go’

Furthermore, Indonesia’s two largest Muslim organisations, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah have been on the receiving end of Beijing’s “skilful diplomacy”, with their leaders visiting Xinjiang and accepting assurances that China is protecting religious freedoms, according to the report.

“The hundreds of Indonesian Muslims studying in China by and large have a positive experience, contributing to an unwillingness to acknowledge serious restrictions on religious practice,” the report said.

Addressing the report, Wahid Ridwan, Muhammadiyah’s secretary of international relations, said that Chinese diplomats had met representatives of the organisation and given their assurances about the Uygur’s religious freedoms.

“They also said not to believe international coverage, especially that published by American organisations,” Ridwan said. “They told us not to believe the report that there are Muslim concentration camps in Xinjiang and to believe China that those are part of their effort to moderate the [Muslims separatists] … they were being very diplomatic about it.”

US slams China’s ‘extreme hostility’ towards religious freedom in report

Last September, Chinese officials invited Muhammadiyah’s senior leaders to Beijing, with representatives of Nahdlatul Ulama making a similar visit two years before that, the report said. China also offered a guided tour of Xinjiang in February this year, where delegations from both Indonesian organisations were shown that Muslims in the far western region were free to pray and study.

“Their largely positive experience, as filtered back to the leadership, reinforced the impression that the Xinjiang issue was primarily about secession, not religion, and Western allegations of human rights violations should therefore be treated with some scepticism,” the report said.

However, the Muhammadiyah delegation reported back to their colleagues in Jakarta, including Ridwan, that they had not been able to interact with any ordinary people during the tour.

“I got the report that they did not talk much to ordinary Uygur Muslims there although our delegation could do Friday prayer and visit the mosques. The tour was great but it did not answer the problem [of alleged human rights abuse in Xinjiang] … there was no dialogue with the Muslims there,” Ridwan said.

In December, Nahdlatul Ulama Chairman Said Aqil Siraj told reporters that his organisation was ready to be a “mediator” between the Chinese government and Uygur Muslims, after meeting China’s ambassador to Indonesia, Xiao Qian.

Foreigner in Papua coup plot: arms dealer or ‘adrenaline junkie tourist’?

But he made clear that Jakarta should not interfere with China’s internal affairs. “Just like us, we don’t want other countries to interfere with insurgencies in Aceh or Papua,” Siraj said.

“Their use of the Uygur issue as a cudgel to attack Jokowi for being pro-China and anti-Muslim has only added to the unwillingness of moderates and Jokowi supporters to be drawn into the fray. To suddenly take a strong position in defence of the Uygurs could be seen as capitulating to pressure from the religious right,” the report said, referring to the Indonesian president by his nickname.

While China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner and second largest investor, its economic importance was not a key factor in informing Jakarta’s response to the Uygur issue, according to the report.

Yeremia Lalisang, an international relations lecturer at the University of Indonesia who spent five years studying in China, said the situation in Xinjiang was not as visible to Indonesians as the persecution of Rohingya Muslims.

“The government wanted to confirm the reports about the treatment of Uygur Muslims in Xinjiang before making the proper response,” he said.

“And there might be a domestic politics factor played into it, we are naive if we say that it does not influence the government response.”

UN counterterrorism chief visits internment camps in Xinjiang

Lalisang, who doubts Western media reports about alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang, said that he had heard from fellow Indonesians who are studying in China that “Muslims’ relations with the Chinese are fine, whether in Xi’an, Xinjiang, or Ningxia”.

“But if we’re talking about separatism, I believe that there are repressive actions taken by the Chinese government because there is a real terrorism threat there,” he said.