Philippine election: torture victim relives horror as dictator’s son Bongbong Marcos rises

- Loretta Rosales, who was tortured and gang-raped by Ferdinand Marcos’ troops under martial law in the 1970s, fears presidential frontrunner Bongbong Marcos will take after his late father

- The Philippines acknowledged abuses in a 2013 settlement that awarded US$190 million in reparations to more than 11,000 victims out of about 75,000 claimants

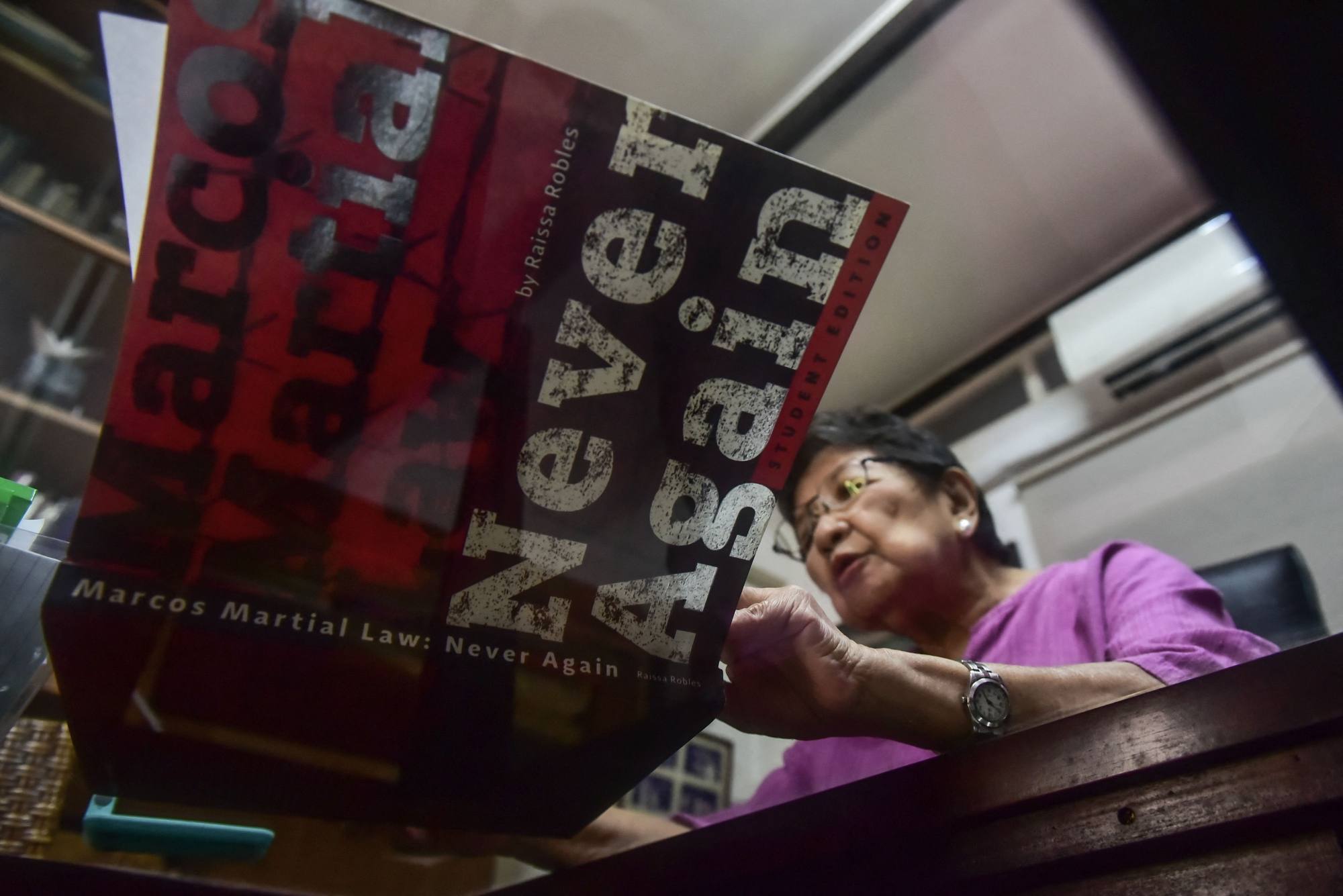

Ferdinand Marcos Jnr’s quest for the Philippine presidency has Loretta Rosales recoiling in horror remembering the nightmare she went through standing up to his late father’s brutal rule.

Tortured and gang-raped by the elder Marcos’ troops under martial law in the 1970s, the former history professor, now 82, said she fears history will repeat itself.

“I don’t want this to happen again to my people,” said Rosales, an activist turned politician who has asked the government to disqualify the younger Marcos, known as “Bongbong”, from the May 9 poll.

She fears he would take after his late father, who shut down Congress and other democratic institutions as well as media outlets while ruling by decree.

Bongbong, 64, is the clear leader in the polls, running on a campaign that steers public discourse away from the crimes of his father’s dictatorship while preaching unity and mapping a path out of the pandemic.

Amnesty International estimates the late strongman’s security forces either killed, tortured, sexually abused, mutilated or arbitrarily detained about 70,000 opponents, according to its Philippine vice-chairwoman Aurora Parong.

A son’s rise: overseas Filipinos throw their support behind Marcos Jnr

Rosales took part in street protests during the period as an activist with the Humanist League, a group aligned with the Philippines’ Communist Party that was the only serious opposition after Marcos crushed most opponents.

In 1976, she was secretly arrested and taken to an unmarked detention house, the former teacher said. Boiling-hot candle wax was poured on her arms and she was waterboarded as well as strangled with a belt.

Her abusers delivered electric shocks to her fingertips and toes, leaving her trembling uncontrollably, and stripped off her clothes, she said.

“Then they started playing protest songs that we sang at our street marches, to taunt you, to dehumanise you,” she recounted.

Rosales said her torturers wanted her to lead them to Jose Maria Sison, founder of the Communist Party which had begun waging a Maoist armed insurgency, as well as her fellow activists.

Bongbong Marcos has downplayed or disputed accounts of abuses committed under the rule of his father.

“I do not know how they (Amnesty) generated those numbers and I haven’t seen them,” he said in an interview with a television channel that aired on January 25. “Let us ask Amnesty International to share that information that they have and maybe it will help us make sure that the system works and alleged abuses that occurred should not occur again.”

Asked about Rosales’ specific allegations, Marcos spokesman Vic Rodriguez said: “There goes Ms Etta Rosales again, pushing very hard her lies to further her group’s gutter politics.”

The Philippine government acknowledged abuses in a 2013 settlement that awarded 9.8 billion pesos (US$190 million) in reparations to more than 11,000 victims out of about 75,000 claimants.

The settlement cited “the heroism and sacrifices of all Filipinos who were victims of summary execution, torture, enforced or involuntary disappearances and other gross human rights violations”.

Payouts were funded from nearly US$700 million held by the elder Marcos in secret Swiss bank accounts that was handed over to Manila in 1995 after authorities concluded the money was plundered from the Philippine treasury.

Rosales said her abusers were plain-clothes “agents” who kept an eye on anti-Marcos groups. Some had even enrolled in classes she taught at a Manila university.

After her torture she was moved to a prison and freed a month later.

She was elected to the House of Representatives in 1998, when one of her torturers, a former paramilitary officer, also won a seat.

She said the man, since deceased, always denied he took part in the abuse.

In 2010 she became head of the government’s independent Commission on Human Rights, a year after the Philippines outlawed torture and “other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment”.

‘Fake news’: Philippines blasts European Parliament in human rights row

The Commission on Elections says 56 per cent of Filipinos registered to vote this year were born after the end of martial law.

Polls project the predominantly young electorate will sweep Bongbong into the Malacanang presidential palace, 36 years after a bloodless uprising ended his father’s 20-year-rule and chased the first family into exile in the United States.

Rosales believes the Marcos family are behind a well-funded campaign to erase their patriarch’s sins from popular consciousness after they were allowed to return to the country following his death in Hawaii in 1989.

“They are pushing the idea that the people power revolution wrecked the fruits of his father’s labour, so that will continue – and that is the worst thing that can happen,” she said. “He’s not the lesser evil. Once he becomes president, he can use force. He will learn (how to use) it.”

Rosales has cited a decades-old conviction for failing to file income tax returns as justification for disqualifying Marcos from the poll, but her petition and several others have been dismissed for “lack of merit”.

That ruling is now on appeal.

For Parong and Rosales, the rise of Bongbong is forcing torture victims to relive their ordeals all over again.

“We really need to do something,” Parong said. “We don’t want another martial law.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)