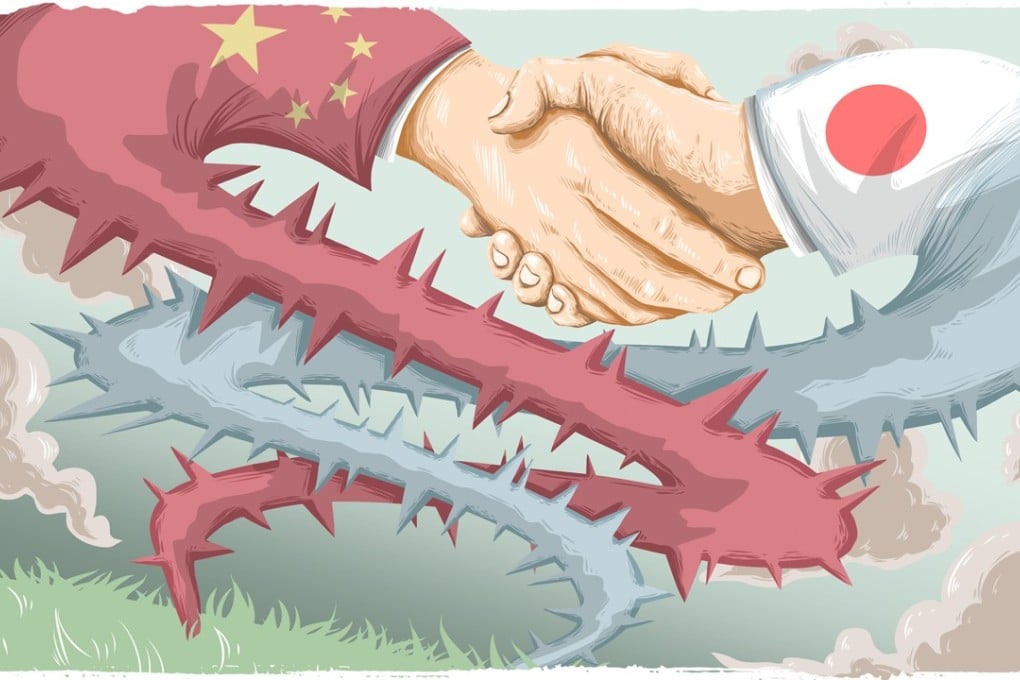

China-Japan ties at ‘historic turning point’ after Shinzo Abe’s visit, but can the goodwill hold?

- Japanese prime minister’s trip aimed to reset relations amid a history of bitter grievances, disputes and rivalry

- Sides agreed to set aside political differences, boost economic ties and promote free trade

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s latest China visit marked a major effort to reset the tumultuous relations between the two Asian giants amid a backdrop of historical grievances, territorial disputes in the East China Sea and geopolitical rivalry in the wake of Beijing’s rapid ascendancy in the region.

In the first official visit by a Japanese leader since 2011, Abe, who wrapped up his three-day trip to Beijing on Saturday, appeared to have achieved his goal of putting ties back on track after a seven-year nadir.

Climaxing Beijing and Tokyo’s efforts over the past year to repair their troubled ties, both sides agreed to set aside their political differences and vowed to boost economic ties and promote free trade amid growing global uncertainty and protectionism.

Amid trade tensions with Washington, the two sides signed over 500 business deals with a total value of more than US$2.6 billion, ranging from infrastructure, energy and car projects to a US$30 billion currency swap pact.

They also agreed not to aim threats or direct aggression at each other and resolved to increase high-level diplomatic and military exchanges through constructive dialogue amid speculation about a planned visit to Japan next year by President Xi Jinping.

Abe said the trip underscored a “historic turning point” in bilateral relations that had hit rock bottom.