South China Sea code of conduct talks may not all be plain sailing next year

- Collin Koh says talks between Beijing and Asean on a code of conduct will continue, but while they do it may be well be business as usual for interested parties

As 2018 draws to a close it is necessary to take stock of what happened this year with an eye on the next.

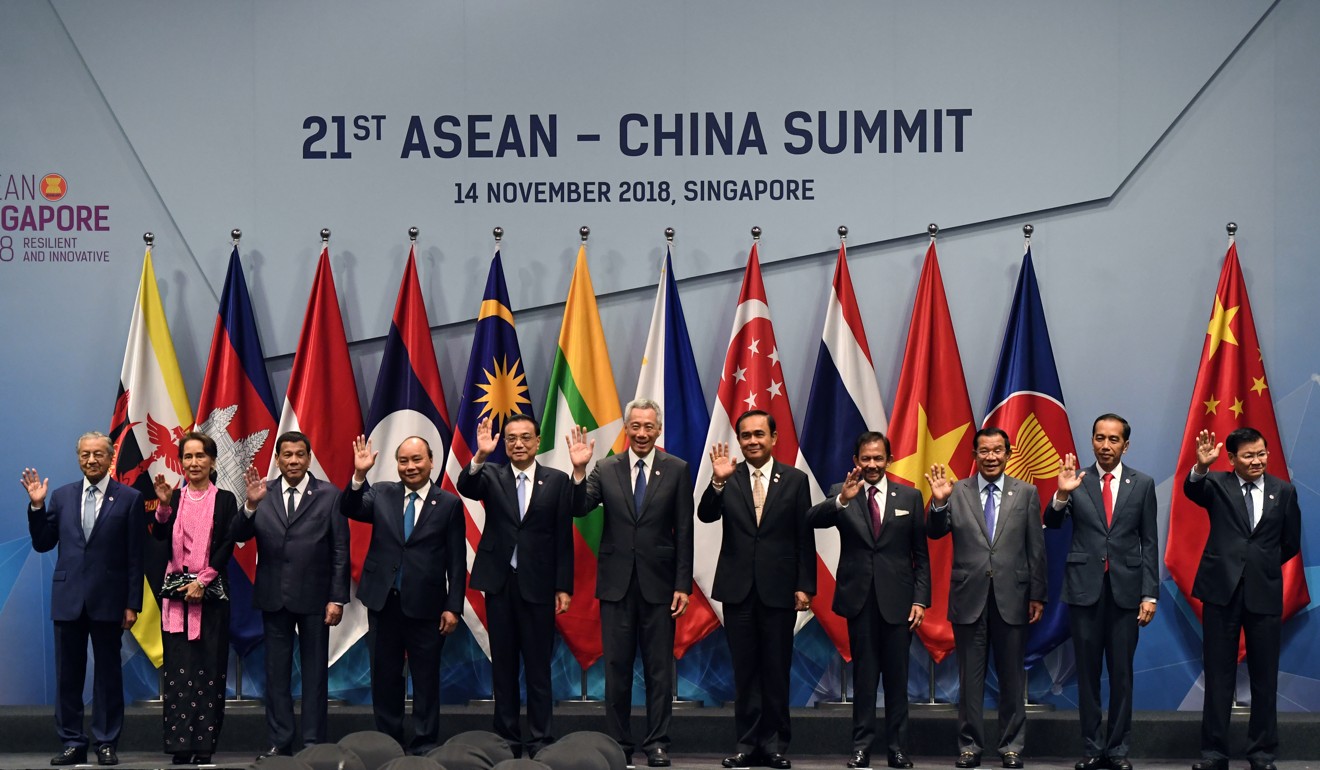

To be fair, much has been achieved as far as Asean and China are concerned, especially over the South China Sea disputes.

The single draft negotiating text for the proposed code of conduct was agreed and the inaugural Asean-China Maritime Exercise was held.

So far, since the September near miss between the Chinese and United States navies in the Spratlys, there have been no further reported incidents.

But what developments can we expect in the coming year? To be sure, Asean and China will proceed with the negotiations on the code of conduct in early 2019, a process Beijing had earlier proposed would take up to three years.

Much may happen throughout the course of the negotiations, and in the absence of a provisional agreement restraining each negotiating party from doing things that may stymie the talks, it is prudent not to expect drastic changes.

Without such a mechanism, much will depend on the goodwill exhibited by each party through the exercise of self-restraint.

This means that some, if not all, South China Sea claimants will continue more or less with business as usual in and around the disputed waters.

Naval, air and coastguard patrols will surely continue. One key issue is the lack of a commonly accepted definition of “militarisation”. Without this, each concerned party – both claimants and non-claimants, including extra-regional powers – will persist with their varying and often conflicting interpretations, and seek ways to consolidate, enhance and strengthen their interests in the waters.

China will continue with its military build-up, training exercises and surveillance in the South China Sea, citing domestic political legitimacy, whereas the US is expected to conduct military activities, including freedom of navigation operations, on the basis of showing its commitment to regional security.

‘Mad Dog was one of the sane ones’: why China will miss Mattis

Regarding the latter, the questions are how often such operations will be conducted and whether the frequency will be more or less or the same as previous years, which could be (mis)construed as a reflection of US commitment.

Probably there is a low possibility that both sides will back down and scale back their activities for the sake of facilitating the code of conduct talks. Moreover, Beijing knows that Asean is highly motivated to push the talks towards its desired conclusion.

While this may not have been often well acknowledged, the truth is that China, not Asean, is in the driving seat of this process.

It can choose to delay, stymie or accelerate this process pursuant to its own interests.

Other concerned stakeholders, not least states whose economic and strategic interests depend very much on freedom of navigation through the waters, may also continue to operate their military forces in the area.

For example, the coming third iteration of the Australian Defence Force’s Indo-Pacific Endeavour will require its naval flotilla to pass through South and Southeast Asian waters.

The Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force, through its Indo-Southeast Asia Deployment, will also need to continue to sail around the region, including the South China Sea.

It also remains uncertain whether the code of conduct will eventually be promulgated with parties outside the 11 governments negotiating the agreement, with future participation in mind.

Philippine lawmaker wants holiday to honour South China Sea ruling

Chances are, these non-signatories will at best give support in principle for the mechanism but not participate as a signatory. It may not be in their interests to sign up to a pact in which they played no part in the initial negotiations.

The question is also whether Beijing will allow their participation, during and following the conclusion of the code of conduct talks, since this move will conflict with its long-standing policy of not internationalising the South China Sea.

Seen in another way, it may even conclude that allowing these external parties to sign onto the code would legitimise their continued presence there.

It would be as if signing up to the code gives a free pass to roaming about freely in the sea – a prospect that Beijing still does not appear to be keen on.

Hence anticipated developments in the SCS in the coming new year will plausibly present a mixed picture, one that is characterised by coexistent parallel tracks of diplomacy in all forms – revolving around dialogue – as well as the exercise of “gunboat diplomacy” for muscle-flexing purposes.

Asean would have much to lose if the talks flounder, and the costs would not accrue as much to China, especially since it has strengthened its physical control in the disputed waters.

Whether the talks continue or conclude, Beijing may have concluded that the international presence in the South China Sea will persist anyway, whether it likes it or not.

Should the Philippines fear a US-China proxy conflict?

In fact, 2019 will see more reasons for a continued international presence in the area.

Asean and the US are planning to conduct their first multilateral exercise – which falls outside the usual slate of US defence and security engagements in the theatre. Another multilateral naval exercise under the Asean framework, organised by Singapore and South Korea and in which Russia is expected to take part, is also in the works.

Japan may also enhance its existing defence and security engagements with its Southeast Asian partners as per its Vientiane Vision road map.

This includes the possible elevation of the Japan-Asean Joint Exercise for Rescue Observation Programme to a table-top exercise.

As such, we may expect talks on the code of conduct to go on, albeit as a process fraught with much uncertainty.

The contentious waters will continue to be crowded – with persistent military and coastguard activities continuing, including continued bilateral and multilateral engagements involving extra-regional players – and in the event of muscle-flexing, the risks of heightening tensions cannot be discounted for sure.

However, one thing we may expect is that following the near collision between the USS Decatur and the Lanzhou, and Asean leader’s open expression of concern, both Beijing and Washington (among others) should be cautious to avoid a repeat.

While the activities and counter-activities of the Chinese and US militaries continue in the South China Sea, both sides are likely to be careful to avoid inflaming matters – unless one overzealous commander decides to take matters into his own hands.

But even if that happens, the chances are that the parties involved in the incident would strive to de-escalate the situations and keep tensions from boiling over.

Collin Koh is research fellow with the Maritime Security Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies based in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore