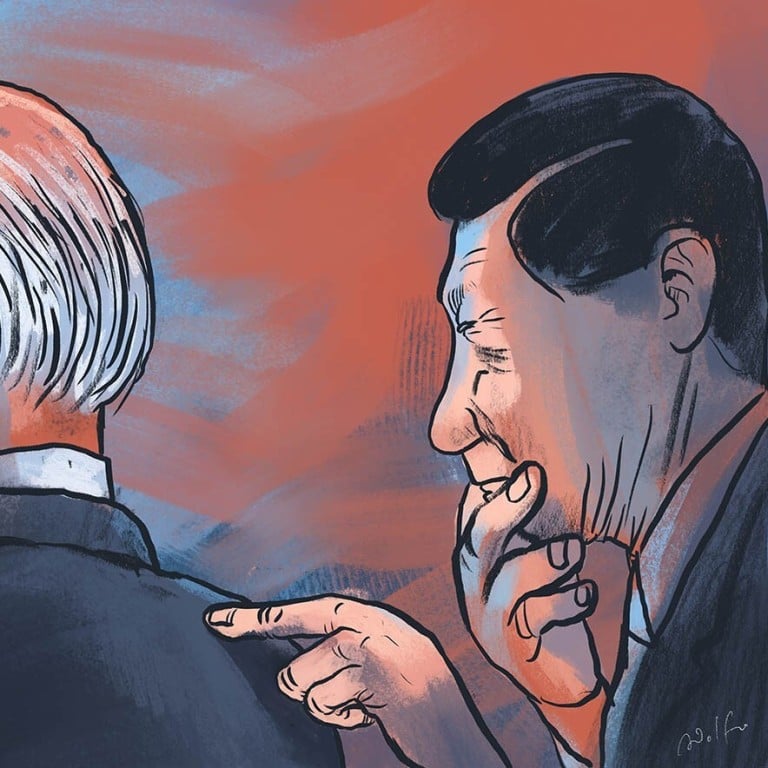

How might China test the new Joe Biden administration?

- The Trump team could meddle in several hot spots before Biden is inaugurated on January 20, including Taiwan and the South China Sea

- Beijing ‘will be watching closely to see if Biden organises the world against China’, says a former US State Department official

As the Biden administration takes the reins in Washington, the stakes have never been higher for the US relationship with China and the rest of Asia. In the second part of a post-US-election series, Washington correspondent Mark Magnier explores how Beijing may test the new US leader and what likely responses might result.

As the likelihood of a US-China reset increases despite the distracting drama over President Donald Trump’s White House departure, former intelligence officials and foreign policy analysts are gaming how Beijing could test the mettle of the incoming Biden administration for weakness and opportunity.

Most expect Beijing to initially take it slow in line with its past approach toward presidential transitions and to avoid jinxing a potential course correction after four brutal years of trade wars, name-calling and recriminations.

“Beijing may try a combination of hard and soft probing as it assesses the incoming administration,” said Jing Sun, associate professor at the University of Denver. “Contacts will be under the surface and incremental due to Beijing being traumatised by the Trump administration.”

Fuelling Beijing’s reluctance to test Washington in dramatic fashion is a belief that it is not in a rush, that American power is declining and that it has met many immediate objectives in the South China Sea. And on other core issues, it has tightened its grip over Hong Kong, while any precipitous move against Taiwan is probably premature, analysts said.

06:04

US-China relations: Joe Biden would approach China with more ‘regularity and normality’

An exception: if a spiteful Trump administration pulls something in its final weeks that Beijing can’t ignore.

“The caveat is if China thinks we’ve done something that compels them to act,” said Paul Heer, a Centre for the National Interest fellow and former East Asia analyst for the CIA, such as a rumoured visit to Taipei by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

“That’s not the kind of thing you can expect Beijing to sit by quietly,” Heer added. “But in general, they want to keep their powder dry to at least have a stable relationship.”

Unplanned events or misunderstandings also can try the relationship, analysts said, as seen with the US bombing of China’s Belgrade embassy in 1999 during the Bill Clinton administration or the downing of a US spy plane off Hainan Island early in George W Bush’s presidency.

An Gang, a Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) fellow at Tsinghua University, expressed concern amid the current heightened tension over Taiwan, nuclear arms control and the South China Sea that the Biden administration could misjudge Beijing’s intentions and overreact, believing incorrectly that China seeks to take advantage of the transition.

New presidents tend to be quite bullish about their ability to change American policy, but almost all tend to be disappointed

Both sides have an interest in “managing and controlling the risk of conflict”, An wrote in an article.

In the complex world of diplomatic probing and gamesmanship, one touchstone will be who takes the initiative on any efforts to reduce tariffs on about US$360 billion in US imports hanging over the global economy and which side travels to the other’s capital. This would likely signal which side feels the greatest economic and political pain and is willing to make concessions.

“It may seem like schoolyard stuff, but there’s some validity to it,” said David Clinton, chair of the political science department at Baylor University.

“I don’t think the Chinese are sentimental. While they want a less contentious relationship, the question is how much they’re willing to pay for it or will Biden want it more.”

Some early signalling on Beijing’s part could include the reining in of nationalistic “wolf warrior” diplomats and even meeting 2020-2021 agriculture purchase targets of US$81 billion under the phase one trade deal, to undercut the narrative that it can’t be trusted.

Related to this is how hard a bargain the Biden administration drives following domestic criticism that past administrations have been pushovers, deluded into believing that China’s state-led system would weaken as its middle class expanded.

Biden, like many in America, fell victim to this thinking as China joined the World Trade Organization in late 2001, said Frank Jannuzi, president of the Mansfield Foundation and formerly Biden’s long-time foreign policy aide in the Senate.

Since then, Beijing’s muscle-flexing has largely shattered that fuzzy lens, he said, even as he acknowledged that China has changed significantly in other ways.

“Joe Biden today is more cautious about China’s trajectory than he was 20 years ago because China’s behaviour has not been consistent with a rules-based international order. And I think he should be,” Jannuzi said. “But he has not closed the door on China.”

Another key part of the wary US-China dance will be sequencing, analysts said, specifically whether the new administration engages directly with Beijing or lets it twist until it forges a common front among allies equally frustrated with China’s intellectual property theft, subsidised state-run companies and human rights record.

“China will be watching closely to see if Biden organises the world against China. And there’s fertile ground there. Europe has been begging for it for years,” said Richard Boucher, a fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute and former senior State Department Asia official spanning several administrations. “That’s what China has the most fear of.”

China will also be watching how aggressively a Biden administration continues Trump’s campaigns against Huawei Technologies, TikTok and other tech players in the race for global supremacy and what an easing might cost. “They want to improve relations without paying much,” said Clinton.

But Beijing also has tools it can wield in return. It can leverage relations with neighbouring North Korea, which is likely to test Biden “kinetically” early on. An analysis by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies of 32 election cycles in the US since 1956 found that the dynastic Communist state is hitting the trigger faster.

Pyongyang provoked Washington within 4.5 weeks on average under Kim Jong-un compared with 5.5 weeks during his father’s reign and 13 weeks for his grandfather.

North Korea’s history of “slicing the salami” with increasingly menacing missile tests – and Beijing’s tendency to effect warmer or colder relations with Pyongyang depending on US-China ties – affords China leverage, said Sue Mi Terry, a CSIS fellow and former CIA analyst.

“Messaging on North Korea is about messaging to Washington,” said Terry, a former deputy national security adviser. “You can get help, or you can get zero help depending on what you do.”

China could also take steps to counter US efforts at aimed isolating it diplomatically.

It can strengthen ties with trading groups and countries economically beholden to it, use its UN perch to thwart human rights investigations and bring about passage of a long-delayed South China Sea code of conduct, undercutting Pentagon efforts at closer Indo-Pacific resistance to China’s expanding footprint.

In apparent preemptive moves, Beijing recently sent envoys to Seoul and Tokyo, urged Europe to chart its own course independent of the US and became a founding member of one regional trade grouping and expressed interest in another, neither of which include the US given Trump’s “America First” policies.

Emerging economies should oppose “long-arm jurisdiction”, President Xi Jinping told the annual summit of BRICS leaders – a grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – earlier this month, in a not-so-veiled swipe at Washington.

China also can “nudge” the incoming administration away from policies it considers red lines, including Taiwan ties or a US declaration that Beijing is guilty of “genocide” for its Uygur detention camps.

12:39

What happened to our parents? Uygur sisters seek answers

This can be done by blocking approval of US diplomats in China and slowing progress on treaties, UN resolutions or bilateral issues, a practice dubbed “pettifogging” in bureaucratic circles.

With past incoming presidents, Beijing has made it patently clear its cooperation was conditional, said foreign policy analysts.

This followed Bush’s vow on CNN that Washington to do “whatever it takes” to defend Taiwan, campaign pledges by Clinton and Barack Obama to get tough over human rights violations and Trump’s call with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen in late 2016 weeks before taking office.

“New presidents tend to be quite bullish about their ability to change American policy, but almost all tend to be disappointed,” said Baylor’s Clinton.

“Obama sent an emissary to Beijing and they came back empty handed. That’s a way you can test a new president. It doesn’t have to do something dramatic but it sends a signal. Maybe you just won’t return their phone calls.”

Personalities can ease or intensify the parrying. Known, predictable players, even if they are disliked, tend to lower the temperature and blunt the temptation to score opportunistic points, analysts said. Biden’s experienced choices, including Antony Blinken as secretary of state, contrast with the revolving door of neophytes seen in the Trump administration.

During the 2001 US spy plane downing – the result of a hot-dog Chinese pilot rather than an intentional Chinese test, many believe – secretary of state Colin Powell and US ambassador Yang Jiechi worked through diplomatic channels to resolve the crisis, even as Beijing made propaganda hay of it in public.

That working relationship paid dividends a short while later when the US sought UN help after the September 11 attack, said Boucher, who was then Powell’s spokesman. “It showed both sides they could work together diplomatically, even with the hardest problems,” he said.

While there’s agreement that China represents a profound, multifaceted challenge, the consensus crumbles on whether it’s primarily an economic or military threat and where confrontation or engagement work best, fissures Beijing can exploit, said Heer, a former national intelligence officer for East Asia.

“There’s a lack of consensus is on what exactly the nature and scope of that threat is and what we should do about it,” he said. “There are lots of fault lines there.”

Most US presidents weather an early foreign policy test that can set the tone for their tenure, said security analysts. John F Kennedy’s failed 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and early meeting with Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, which led the Russian leader to conclude Kennedy was a pushover, helped fuel the Cuban missile crisis the next year.

“Worst thing of my life … he savaged me” Kennedy said later.

Bush was taken aback by the Hainan Island spy plane downing. Obama was criticised for appearing weak, allowing China to militarise the South China Sea despite Xi’s assurances.

“Let’s face it. In the end, the US is the big prize for China and China is the big prize for the US,” said Boucher. “Each side is going to be looking for whatever advantage they can get.”

Reporting was contributed by Wendy Wu