Chinese writers steer path round censors to earn cash through apps

Bloggers turn to popular web platforms to connect with their readers and make a living – so long as they stay within the bounds of the ‘Great Firewall’

When outspoken professor Qiao Mu posted his resignation letter on a popular Chinese messaging app, sympathetic readers tapped their phone screens to send him money, leaving him with a 20,000 yuan ($3,000) payday.

China’s widely used applications have given writers like Qiao an outlet to self-publish and make money – as long as their words respect the boundaries set by online censors inside the country’s “Great Firewall”.

With Facebook and Twitter blocked in China, they post their works on WeChat, a messaging service with over 900 million worldwide users, or Weibo, a microblogging website – both monitored by the Communist authorities.

“I’m a typical Chinese person. I love my country and I want to change it. To reach the majority of the Chinese people I need to stay inside the Great Firewall and write in Chinese,” Qiao told AFP.

Qiao, 47, quit his library job because he was fed up of doing dull translations after getting banned from teaching in 2014 for vague “work violations”.

Growing pressure on writers and academics is part of a tightening of controls on civil society that began in 2012, when President Xi Jinping took power.

In April, Qiao, the former director of the Beijing Foreign Studies University’s international communication studies programme, posted his resignation letter on WeChat.

“[University officials] said I wasn’t being positive in my research, that I was being careless in the articles I was publishing,” wrote Qiao, who made 200,000 yuan a year as a library manager.

“I’ll need to get used to my new life. ... At least after I resign my speech will no longer censored by anyone but myself and the internet censors,” he concluded.

Run by Chinese internet giant Tencent, WeChat allows users to post content on public accounts, where followers can tip whatever amount they want.

Qiao usually makes at least 1,000 yuan ($145) for each short essay. The average monthly salary in China is 6,070 yuan.

He has opened 15 public accounts on WeChat since 2012, but most were shut down by censors after he posted political commentary.

One of his three remaining accounts has 15,000 followers. If an article is blocked, he moves it to another account.

“In a way, it is a sort of democratisation of the literary world. By giving rewards to the people they like to read, netizens can create their own new literary hits, influencing the status quo of China’s literature today,” said Manya Koetse, who tracks social trends in China as editor of What’s on Weibo.

“There’s been a rise of literary platforms that tell fresh and individual stories of ordinary people instead of high-profile names,” Koetse said.

Independent writers can also earn income by accepting advertisements or sponsored content on their public accounts.

Mi Meng – whose writing style has been compared to Sex and the City’s protagonist Carrie Bradshaw – boasts more than 10 million WeChat subscribers and posting ads on her account can cost as much as 500,000 yuan.

Others team up with fellow writers to start online publications that focus on certain topics and rely on advertising for income.

In 2014, Ye Weimin left his job as senior editor at Southern Weekly in Guangzhou following crackdowns on the newspaper, which has pushed the boundaries of censorship with hard-hitting investigations.

Ye, who now works in finance in Beijing, charges download fees for his journalism tutorial videos.

“I didn’t expect almost 3,000 people to pay for my online tutorials. This is completely accidental income,” he said.

In 2013, Chinese authorities moved against influential online commentators, arresting some and shutting down many of their accounts.

China’s top court also ruled that year that people would be charged with defamation and potentially face jail if “online rumours” they started were viewed by 5,000 internet users or reposted more than 500 times.

New regulations launched in June require online platforms to get a licence to post news reports or commentary about the government and a slew of other issues.

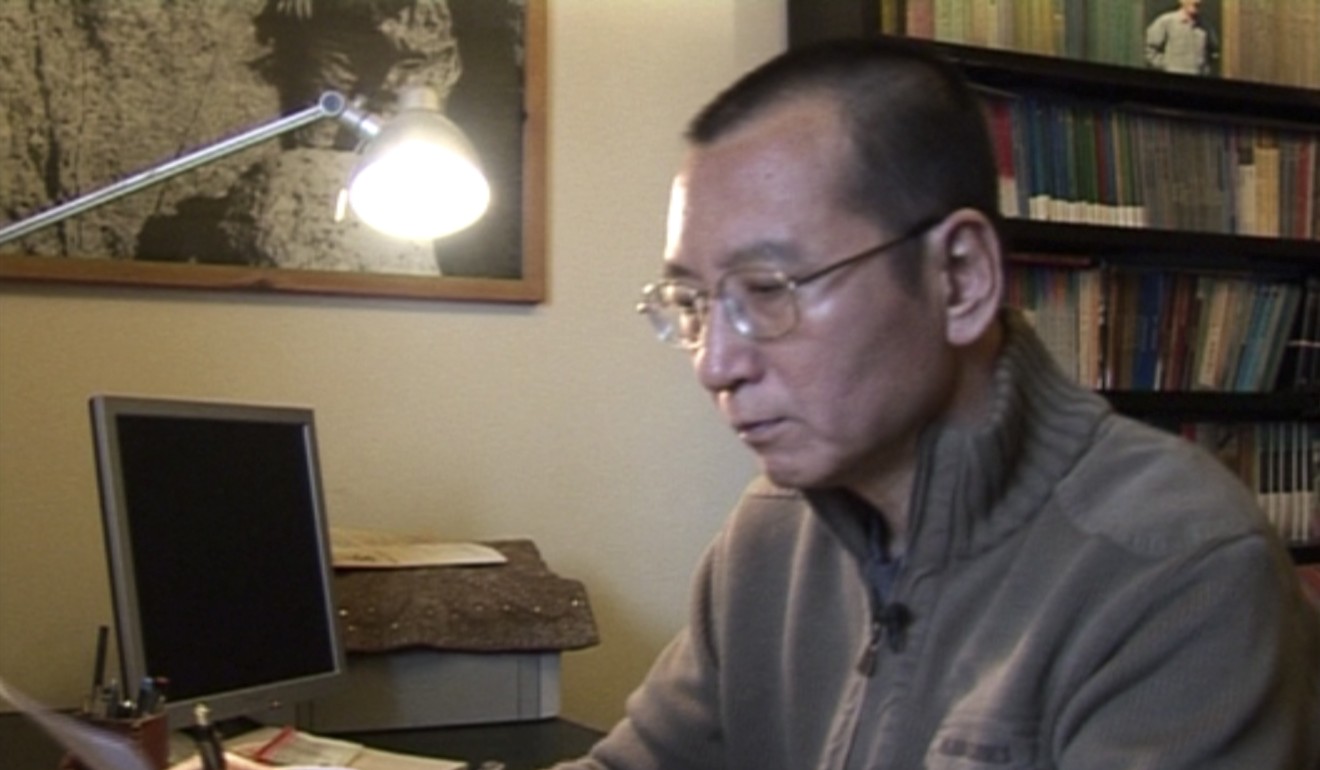

Qiao occasionally tests the limits of censorship, such as a post commemorating the July 13 death of dissident Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo.

“I didn’t criticise the government in the article. I was just paying tribute to a man and his contribution to peaceful dialogue, but it was immediately deleted,” Qiao said.

“If my writing is too political, no one will read it and my account will get deleted. People like to be entertained, and they know how to read between the lines,” he said.

“I self-censor to survive.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)