Foreign journalists in China report state backing for rising intimidation during Henan floods

- Years of encouragement for nationalistic sentiment is behind the intense hostility faced by reporters, observers say

- Previous campaigns against Western news outlets were confined largely to the internet but this time there was anger on the streets

In one of the worst reported cases, two journalists were surrounded by an “angry mob” in the provincial capital of Zhengzhou on Saturday as they reported on the floods, according to Mathias Boelinger, from German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle. He shared video footage of the incident which showed a man grabbing him and trying to take away his filming equipment.

“They kept pushing me, yelling that I was a bad guy, and that I should stop smearing China,” Boelinger said, in a series of tweets he posted on Sunday.

Boelinger, who believes he was mistaken for the BBC’s China correspondent Robin Brant, was with Alice Su, Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, who was also reporting on the floods when the incident happened. She has also been targeted online.

Liu Ludong, an outspoken nationalist with more than 6.5 million followers on microblogging platform Weibo, called for Su’s deportation and asked Peking University – where she completed a degree – to “strengthen the inspection of international students’ political background and cultivate fewer enemy collaborators like Su.”

The harassment was condemned by the BBC, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China (FCCC) and press freedom NGO Reporters Without Borders. The BBC said in a statement on Tuesday “there must be immediate action by the Chinese government to stop these attacks which continue to endanger foreign journalists”.

In a statement issued on the same day, the FCCC said the growing hostility was underpinned by “rising Chinese nationalism, sometimes directly encouraged by Chinese officials and official entities”.

Keith Richburg, director of the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong, said that what happened in Zhengzhou was novel because official bodies like the Henan Communist Youth League were calling for journalists to be physically followed. “This [kind of rhetoric] puts reporters’ lives in danger,” he said.

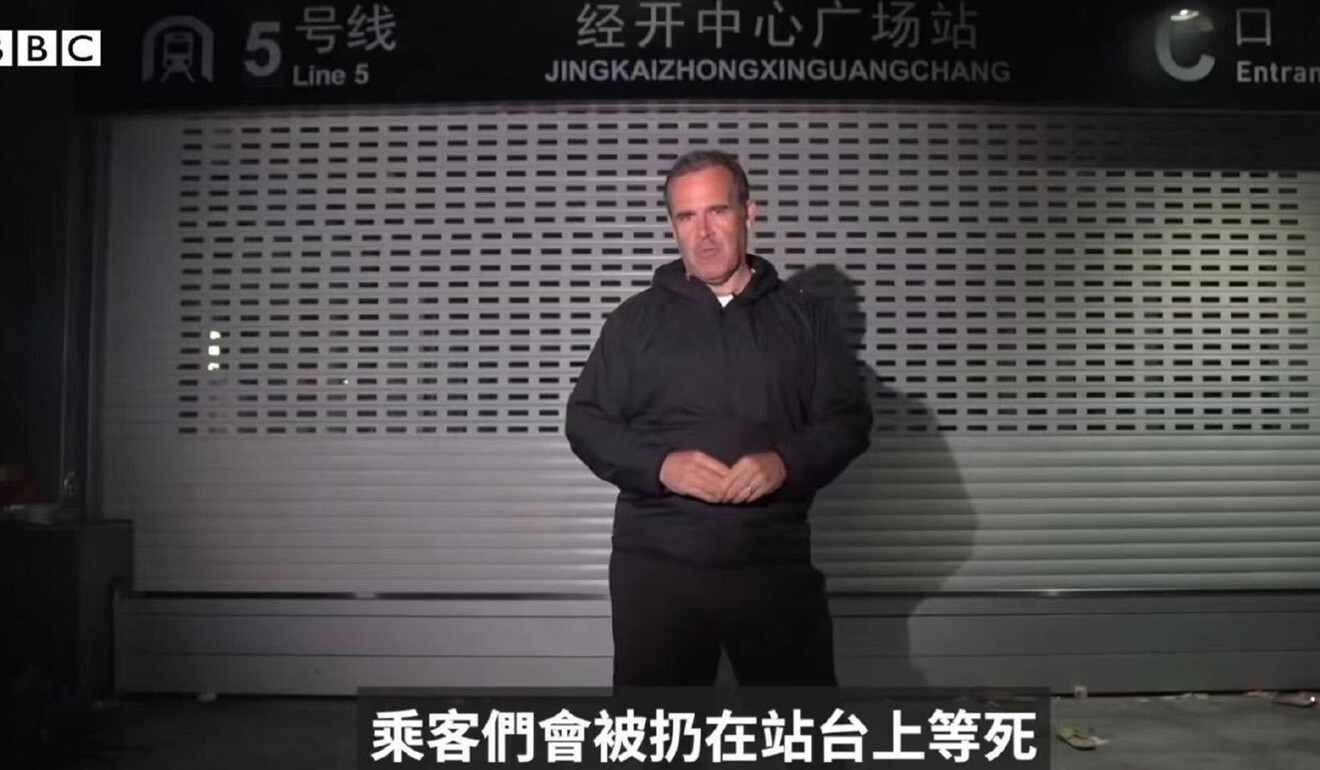

A few days before the incident, “BBC spreads rumours” was trending on Weibo, but it was also promoted by Chinese state media, including the Xinhua news agency, and an online nationalist group known as Diba. The hashtag was prompted by Brant’s July 22 report for the BBC – from in front of the subway station which had flooded two days earlier leaving 14 dead – in which he said passengers “were left to die”.

The Henan Chinese Communist Party Youth League, which has one million followers on Weibo, called on people to follow Brant and share information of his whereabouts in the comments section. Clips of Brant’s reporting from Zhengzhou were frequently attached to the BBC rumours hashtag, along with pictures of Boelinger. The hashtag was also used to target Katrina Yu, a correspondent for Al Jazeera, with a video of her in Zhengzhou also uploaded to Weibo on Saturday.

“A friendly reminder to all Zhengzhou resident friends – do not accept interviews from foreign media! Do not be used!” read the caption on the video.

Wu Qiang, a Beijing-based political commentator, said foreign journalists being treated with such hostility as seen in Henan was a result of “years of rising tides of nationalistic sentiment”. He said anti-US and anti-British sentiment were “thrown into the mix” of the public response.

Nationalistic outbursts against Western media in China are not uncommon. In 2008, 23-year-old student Rao Jin founded Anti-CNN, a website that said its purpose was to “collect, classify, and exhibit the misbehaviour of Western media”.

Rao was interviewed by state-run domestic outlets like CCTV and the website was given tacit approval by then-foreign ministry spokesman Qin Gang, who this week arrived in Washington as China’s new ambassador to the US.

However, the anti-CNN campaign was largely confined to the internet, unlike the recent hostilities, according to Richburg.

Foreign journalists welcome if they ‘present true image’ of China: diplomat

The state-run China Daily published an English-language video on Wednesday in which two of its reporters called Deutsche Welle an “international propaganda agency” and said the anger towards foreign reporters was “well based”.

Foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian responded to the controversy on Thursday, saying “there is always a reason for love, and also for hate”.

Other responses to the controversy were more measured. Yang Liu, a Beijing-based journalist with Xinhua, tweeted on Monday that he was treated well by locals during overseas postings and he hoped for the same for his foreign colleagues in mainland China. “I hope all foreign journos can be treated well, especially at a time when mutual understanding is crucial,” he wrote.

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Global Times, a nationalist tabloid affiliated to party mouthpiece People’s Daily, published a lengthy article on Sunday that was widely shared on Chinese social media. While he described the public rage against Western media reports as “completely justifiable”, He emphasised that physical harassment was not appropriate because it would only “help them further smear China with more forceful language”.

04:02

Zhengzhou residents mourn subway flood victims in China’s central Henan province

“We strongly advise the public in all places to not surround Western journalists on the scene,” he wrote. “As long as these journalists have not destructively involved themselves or interfered in the actual situation and are recording [events] as interviewers, it is inadvisable to use coercive means to prevent them from filming.”

The FCCC said on Tuesday that Chinese government censorship of foreign media “has contributed to a one-sided view of our work in China”. The club published a report in March that said 18 foreign correspondents had been expelled last year.

Richburg, who was The Washington Post’s Beijing bureau chief from 2010 to 2013, said that, for all the accusations of ill will against Western media, China often used overseas tragedies to boost the government’s domestic legitimacy, even as similar events within its own borders were censored.

“They are OK with mocking other countries when they are suffering, but not with foreign reporters pointing out some of their own faults,” he said.

China ‘using visas as weapons’ against foreign journalists

On July 11, for example, foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying tweeted about the rescue mission in the US for Florida residents trapped after a building collapse which left 95 dead. “What about the 100+ lost lives? It’s really hard for #Chinese to understand this kind of #US #humanrights,” she wrote.

Less than two weeks later, several articles on the Zhengzhou floods were removed, with 11 so far identified and stored by China Digital Times, which archives Chinese-language articles censored behind the Great Firewall.

One article published on Monday – and quickly censored – by Chinese journalist Sun Zhibiao, was critical of the hostility encountered by Boelinger and other foreign journalists in Zhengzhou. He connected it to the wolf warrior brand of diplomacy, for which Hua has become well-known.

“As external propaganda becomes more like internal propaganda, foreign journalists have also become enveloped in the emotional outpouring of [domestic] Chinese public opinion,” Sun wrote. “Boelinger entered what he thought was the right place, but at the wrong time.”

Boelinger declined to comment for this article.

The effect of the campaign against foreign journalists was evident in a video originally broadcast on Tuesday and shared widely on Weibo. It showed two survivors of the subway deluge talking to reporters from local media outlets about their ordeal.

A fuller version of the video uploaded to Twitter on Thursday showed the women ended the interview when a man was heard to say: “No foreign media here, right? Give the full story, don’t smear.” The exchange was not included in the versions shared on Chinese social media platforms.