Diabetes in Chinese-Canadians linked to immigration policies favouring the rich and skilled, study suggests

- Researchers on Ontario found immigrants from mainland China were at far greater risk of young-onset diabetes than those from Hong Kong or Taiwan

- Dr Calvin Ke says economic immigration policies could have health implications for decades to come

Canadian policies seeking wealthy and high-skilled immigrants may be influencing diabetes rates among its Chinese communities, according to a study which found mainland Chinese newcomers at greatly elevated risk compared to compatriots back in China, as well as fellow immigrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The “unexpectedly heterogeneous” diabetes rates between the three groups demanded urgent and targeted public health strategies, said the study, published in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice last month.

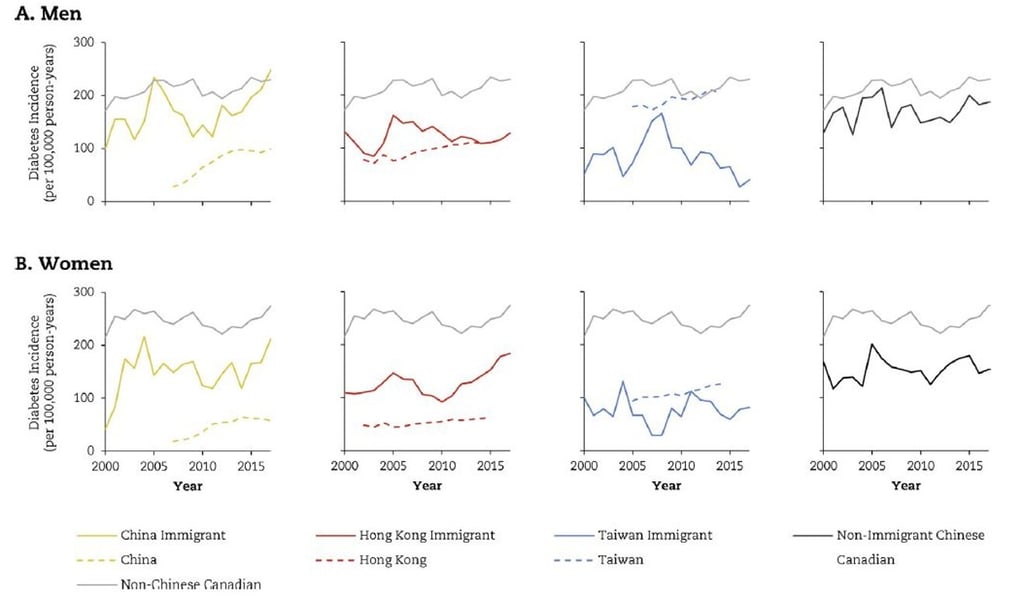

The study said that mainland immigrants suffered young-onset diabetes at a rate more than 2.5 times that of China’s general population; 37 per cent higher than that of Hong Kong immigrants in Canada; and 111 per cent higher than that of Taiwanese immigrants.

The findings undermined notions about a homogenous Chinese community in Canada, and suggested immigration selection decisions could have health policy implications for decades to come, said endocrinologist Dr Calvin Ke, the lead author of the peer-reviewed study.

“Canadian health care providers need to be aware of the impact of immigration and ethnicity on diabetes. We can’t just lump everyone who is Chinese together into the same category,” said Ke, a University of Toronto Global Scholar who has researched diabetes in Canada and around the world.

“This is what policymakers need to take into account – when your policies select the wealthiest or the highest skilled, the most educated, that will have different implications for health outcomes.”