Have Occupy Central organisers already committed a crime?

Those behind Occupy Central movement should take care to avoid being arrested for conspiracy

There is growing concern with the public order or obstruction offences that may occur next July 1 from the Occupy Central movement. Could the movement's organisers have already committed criminal offences simply by planning and encouraging others to join in?

If you and I planned an armed robbery of WXYZ bank in Central next summer, we would have committed the offence of conspiracy to rob. This is because we agreed on a course of conduct to be pursued which, if carried out in accordance with our intentions, would necessarily amount to the commission of an offence (Crimes Ordinance, s. 159A(1)).

Does it matter if our intention were conditional, such as only if "the coast is clear" (Lord Nicholls in Saik (2007)), if the Hang Seng Index falls below 19,000, or if the chief executive fails to deliver an acceptable reform proposal for universal suffrage?

The English and Hong Kong position is that such conditionality generally does not matter, except in two situations. The first is where the condition is so far-fetched that it negates the intent. Lord Nicholls gave the example of agreeing to commit an offence "should I succeed in climbing Mount Everest without the use of oxygen". The second exception, as outlined in the English Law Commission's 2007 paper, is where satisfaction of the condition would negate liability for the offence. For instance, agreeing to broadcast on radio only if granted a licence to do so.

But neither exceptions appear to apply to the Occupy Central movement. With its deliberation dates and threat of civil disobedience, the movement appears intent on committing offences, albeit as a last resort, if the chief executive cannot deliver on universal suffrage, which is hardly a fanciful possibility.

The English case of O'Hadhmaill (1996) is instructive. The defendant - coincidentally also a university lecturer, but a member of the Irish Republican Army - was charged with conspiring to cause an explosion, after explosives and other weapons were found in his car. At the time, the peace process leading to a ceasefire was under way, and it was argued he had no intention to cause an explosion.

But the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction, finding that the agreement and intention were settled although the plan was to be cancelled if the ceasefire succeeded. "The fact that some supervening event in the future might cause a change of mind would be no answer to the charge." But if the defendant had yet to make up his mind to use the explosives, he would not be guilty.

Occupy Central organisers should heed the implications of this analysis if they wish to avoid immediate arrest for conspiracy. First, it should be made clear that minds have not been made up to occupy - even if they are dissatisfied with the reform proposal for implementing universal suffrage. Second, to fall within the second exception, organisers should make it their platform that they are only promoting conduct that is justified or excused under the law, rendering the element of civil disobedience irrelevant.

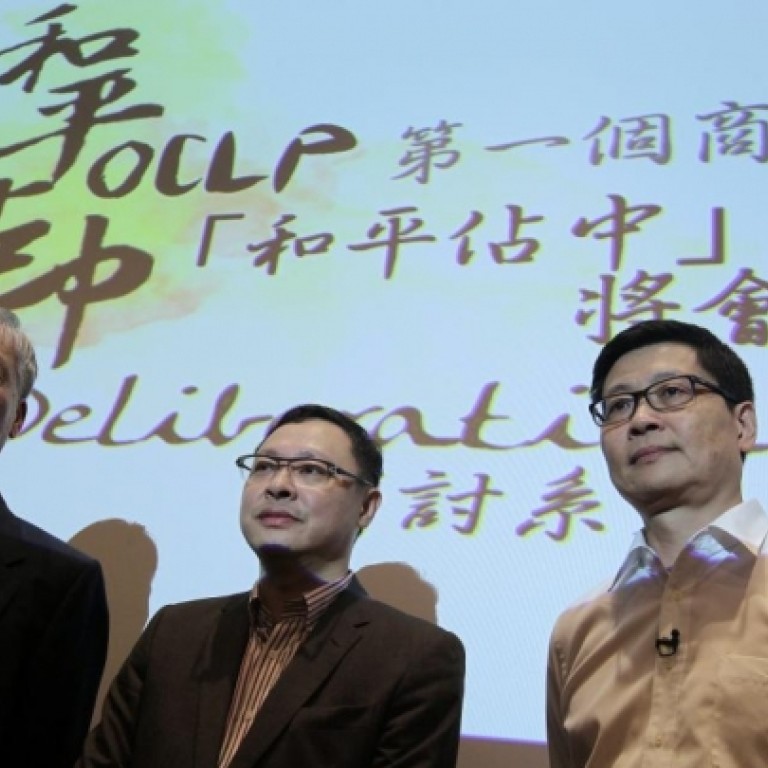

Professor Simon Young Ngai-man is director of the Centre for Comparative and Public Law at the University of Hong Kong's law faculty