What is the currency of Hong Kong? How a city’s money came to be, from fresh bills to going cashless

- First local bank issuing currency notes opened in 1845, and before that, myriad money types changed hands, from foreign silver coins to the Indian rupee

- New bills set to be rolled out by the end of the year with fresh designs and advanced anti-counterfeit measures

Hong Kong’s HK$2.7 trillion (US$341 billion) economy is run with its own dollar, a currency that has lasted through decades of British colonial rule to the city’s contemporary position as a special administrative region of China.

Despite this history, the Hong Kong dollar, or “HKD”, is most closely associated with the US dollar, instead of with the British pound or Chinese renminbi.

Evolving with the city as Asia’s financial hub, Hong Kong dollar bills and coins have taken on different designs and symbols through the decades, printed and minted by local banks but pegged to the US dollar for more than 30 years.

How does Hong Kong decide its currency’s exchange rate?

Hong Kong’s currency only fluctuates within the range of 10 HK cents. As a “linked” currency, the value of the Hong Kong dollar is set relative to the US dollar. The Monetary Authority carefully maintains the exchange rate of HK$7.75-7.85 to US$1 by buying or selling reserves when needed.

“The system was introduced in a quick manner to stop the dramatic depreciation of the Hong Kong dollar at the time,” City University economics professor Cheung Yin-wong said.

“The move was confusing for the market, but one message was very clear: the Hong Kong government was determined to defend the monetary system and the value of the Hong Kong dollar.”

Before the peg, the city had experienced about a decade of free-floating currency, preceded by decades of set exchange rates with the British pound.

When it comes to the relationship between the Hong Kong dollar and renminbi, the two currencies may move in similar directions, but that is not vis-à-vis their relationship to each other. Instead, Cheung explained, this phenomenon is more likely to occur because their values react to the strength of the US dollar.

At present, both are weak compared to the US dollar.

What currencies have been used in Hong Kong?

The Hong Kong port of the early 19th century was a melting pot of currencies, with silver coins such as those of Spain and Mexico, the Indian rupee, British sterling, and Chinese “cash” coins and silver tael changing hands.

It was not until 1863 that the colonial government named the silver dollar as legal tender. A local mint began issuing the first Hong Kong coins three years later, but closed in 1868.

In subsequent decades the accepted currencies were whittled down. An 1895 edict limited legal tender to the Mexican dollar, British trade dollar, and Hong Kong dollar, printed by several newly established note-issuing banks. All foreign currencies including that of China were banned from circulation in 1912, the same year a nationalist democratic revolt overthrew the Qing dynasty emperor.

The currency was standardised in 1935, but disrupted during the Japanese occupation when Japanese military notes were exchanged for daily transactions.

In 1997, even as Hong Kong transitioned from British to Chinese rule, the city’s dollar remained in place. But the city also holds the world’s largest supply of renminbi outside the mainland as an offshore centre offering financial services in that currency.

What’s behind the design and symbols of Hong Kong’s currency?

Hong Kong money has gone through numerous transformations, but the most symbolic might be the switch from the queen’s head coins, bearing the profile of Queen Elizabeth, to the post-handover coin, which sports Hong Kong’s bauhinia flower. The iconic queen’s head coins stopped being issued in 1993, but still pop up in wallets across the city.

Paying with your smartphone still not catching on in Hong Kong

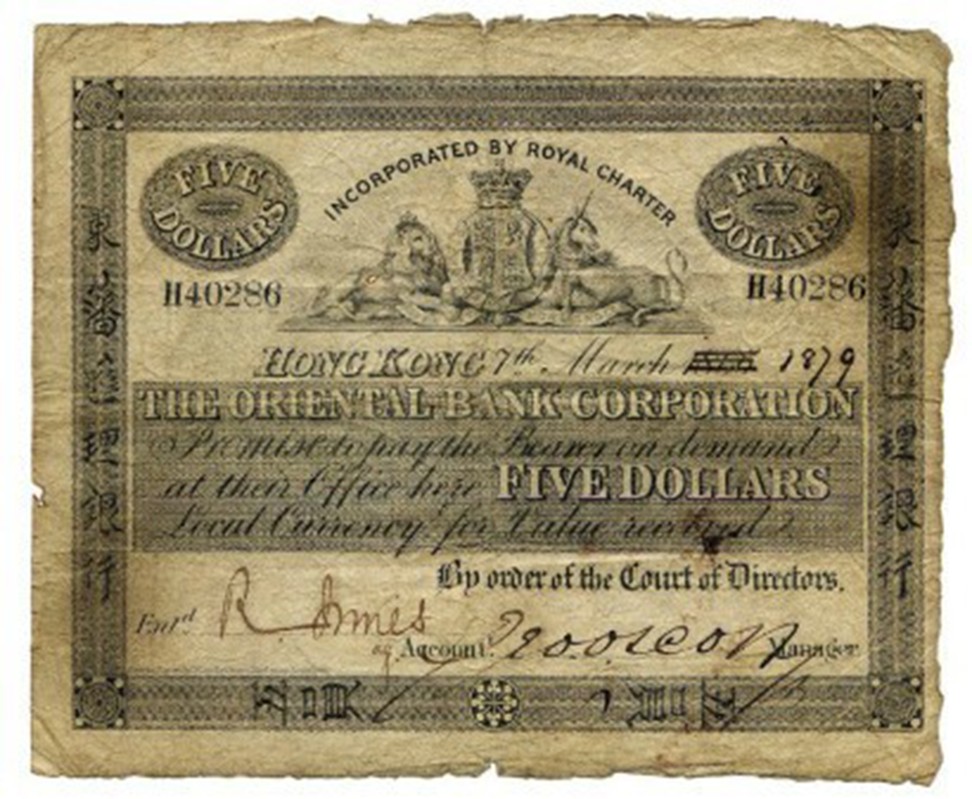

Hong Kong’s dollar bills have been evolving since the first issuing bank was opened in 1845. Three banks now print Hong Kong’s currency: HSBC, Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) and Bank of China (Hong Kong). Each is authorised to print its own distinctive designs.

How close is Hong Kong to going cashless?

The ubiquitous Octopus stored valued card was a global forerunner of cashless payment when it was launched in 1997, but while the city still runs on cash, credit or debit cards, as well as Octopus, mobile payment apps in mainland China have all but overtaken other modes for small transactions.

Hong Kong halts auto e-wallet top-ups after reports of missing funds

But a host of mobile payment providers, both local and regional, are vying to be the city’s e-wallet of choice, and about 40 per cent of Hong Kong businesses, including 7-Eleven stores, offer mobile payment options.

As Hong Kong eyes its “smart city” blueprint for advancing how technology is integrated into urban life, less colourful paper cash and more mobile scans may be on the horizon. The city is therefore planning to strengthen its mobile payments infrastructure, including having standardised QR codes.