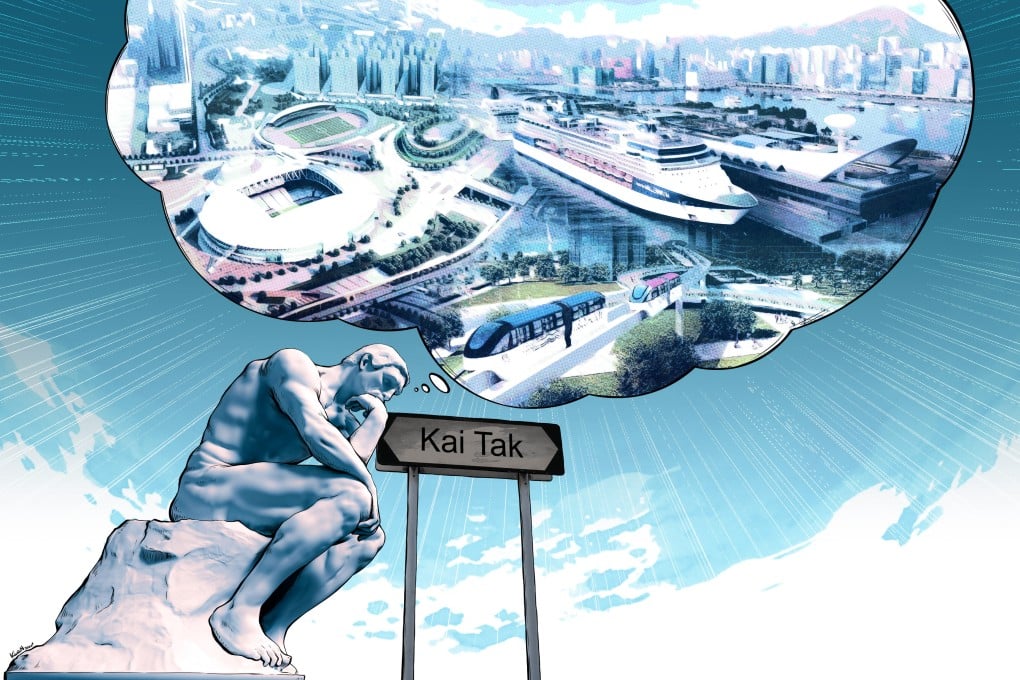

Kai Tak dreams fizzle: Hong Kong’s massive ‘second CBD’ project slowed down by delays, changes to original plans

- Rezoning of commercial sites, appearance of Covid-19 facility raise questions about ‘CBD2’ plan

- Developers, homebuyers still unhappy that government scrapped ‘too costly’ monorail proposal

One Victoria, a three-block condominium project was completed this month, but the 36-year-old found his new home in the middle of a massive construction site, with no public transport.

“There is a lack of planning for such a huge site. It’s laughable,” he said.

His property is on a 3.9km strip that used to be the airport runway. It is part of the 320-hectare Kai Tak Development, which is quarter the size of the city’s Central and Western district, and eight times bigger than the West Kowloon Cultural District.

Ambitious plans for the area drawn up 15 years ago envisioned a bustling residential and commercial district with green spaces, and a sports and leisure hub that would draw Hongkongers and visitors alike.

The project was expected to take shape from 2013, but was hit by delays made worse when the economy was affected first by the social unrest of 2019 and then the Covid-19 pandemic.