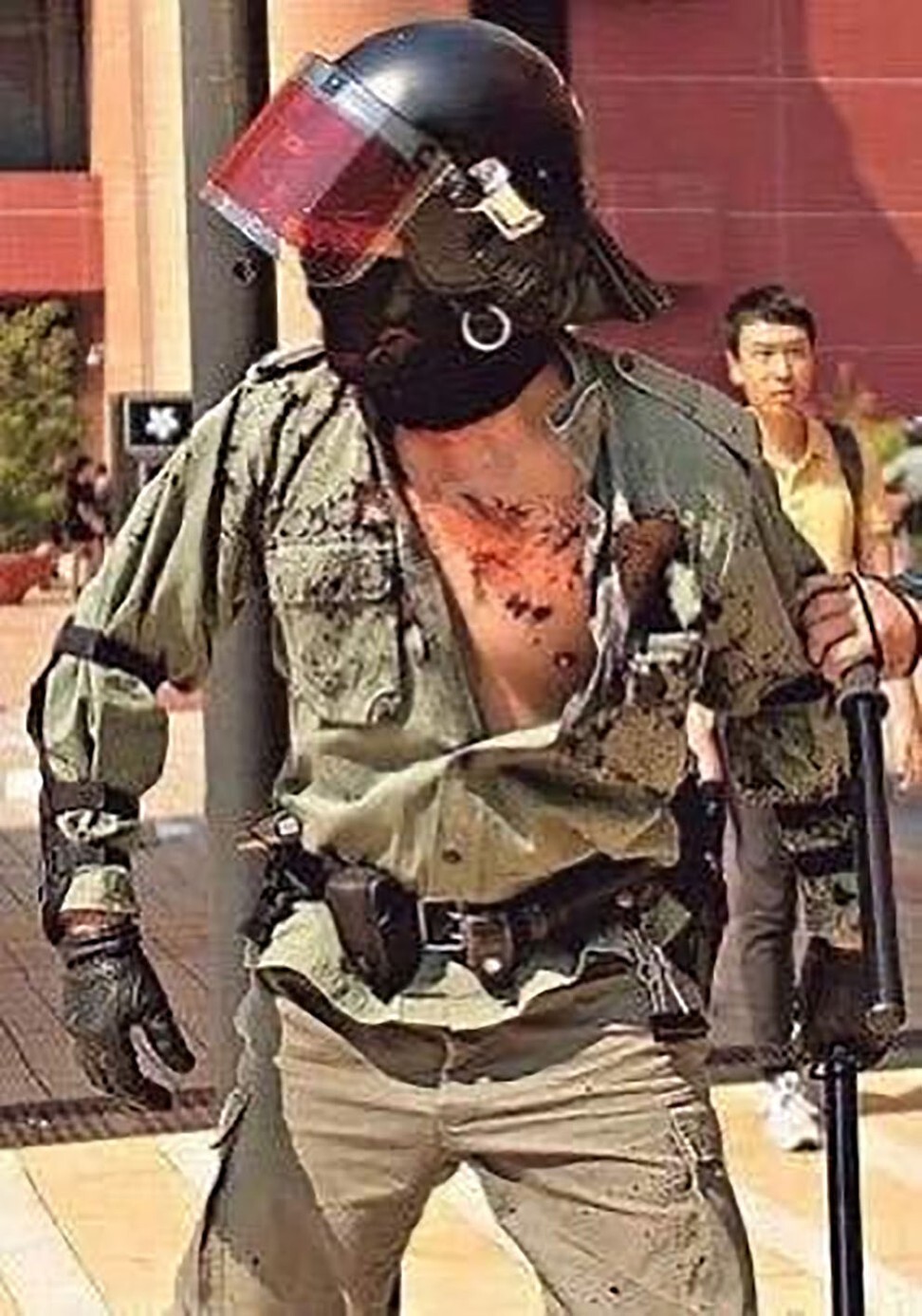

Hong Kong protests: police officer who suffered severe burns at Tuen Mun rally says: ‘I have no desire to know who hurt me’

- Constable was sent to protect district’s town hall on National Day when he was hit with corrosive liquid that dissolved skin and muscle

- He spent nearly two months in hospital and will feel physical pain for the rest of his life, but says he harbours no anger towards his attacker

As Hong Kong marks a year since the anti-government movement began, we analyse how key players have fared. This is the fourth article in the series .

Police constable Ling* touched his chest to find the fabric of his uniform melting away. His colleagues were staring at him in horror as skin and muscle began to dissolve before their eyes.

It was National Day and the 38-year-old had been hit by a bomb of corrosive liquid hurled by an anti-government protester in Tuen Mun.

He knows he could have died that day if not for the protective gear around his neck. But the severe burns destroyed nerves, leaving a large scar that extended down his chest and back. Some of the injuries will cause him pain for the rest of his life.

“My friends across the border described my scar as a medal,” Ling told the Post. “I do not want to flaunt my wound like this, but it was my honour to take part in that historic mission. My injury is not a big deal, pain is something I can endure.”

After undergoing five operations, spending 50 days in hospital and being on medical leave for another 53 days, Ling returned to duty at the emergency unit of the New Territories North Regional Headquarters on January 12 and is back with the frontline team.

Ling said the experience left him more mature, even optimistic. “My injury gave me a lot of time to think about life. I am more carefree now and look at matters from different angles,” he said.

Tipping point for security law? PolyU and Chinese University protests: source

Encouraged by an injured colleague, he opened a Weibo account after his ordeal. Positive messages flooded in quickly from more than 15,000 followers on the Chinese social media site, and a dozen have since become his friends.

“At first, they sent me their regards and asked if I was at this or that scene. As time went by, we began talking about personal matters,” he said.

The person who tossed the bomb that injured him was not caught, but Ling said: “I have put aside the matter and have no desire to find out who hurt me, because the effort will be futile. I am better off having one foe fewer.”

Growing up in Sheung Shui in the northern New Territories, Ling recalled being sickened when he saw gangs recruiting members outside schools and bullying youngsters on basketball courts. The experience prompted him to join the police to tackle crime.

He did not realise that being a police officer would cost him so many of his friends. After the 2014 Occupy Central movement, when protesters shut down parts of Hong Kong for 79 days, almost all his friends outside the force deserted him because of his job and political stance.

Can Hong Kong police chief’s new strategy cripple protest movement?

Over the second half of last year, as anti-government protests grew increasingly violent and rampant, police responded more aggressively at the front line, deploying crowd dispersal weapons and arresting thousands of participants.

More than 1,700 protesters and 600 officers were injured during the unrest. One was slashed on the neck, another shot in the calf by an arrow, and a third had part of a finger bitten off.

Ling’s first deployment during the unrest was at the Legislative Council complex on the night of July 1, but he was only there to clean up the mess left by protesters who had earlier stormed and vandalised the building.

His chance for some frontline action came on October 1. He was part of a team sent to protect the Tuen Mun Town Hall and surrounding areas amid indications protesters intended to turn up to desecrate Chinese flags on National Day.

Ling arrived at the town hall at 7am. At around 11am, a small group of protesters appeared and began to vandalise the area, with one attempting to spray graffiti on walls.

His team moved in and arrested about 10 people. Within the next two minutes, nearly 1,000 protesters materialised and began attacking the officers, hurling corrosive bombs.

Defeat for Hong Kong protesters? One year on, pulse and purpose changes

As he tried to get the team and the arrestees to a safe area, he was suddenly overwhelmed by a painful, burning sensation. He only realised the extent of his injuries when he arrived at hospital. Ling, who is single and lives with his parents and sister, did not want his loved ones to see what had happened.

“I could not bring myself to see them from my sick bed,” he said. “I only allowed them to visit when I could get out of bed and walk, so that they could see that I was all right.”

Even then, he told his family not to tell anyone what had happened, fearing outsiders would mock them for having a policeman in the family. “I didn’t want them to suffer or lose friends because of me. Telling others won’t help my skin grow back anyway,” he said.

As the anti-government protests continued, police were accused of using excessive force and brutality, triggering demands for an independent inquiry.

Explainer: How the Hong Kong protests erupted – and what lies ahead

Ling felt the accusations were largely unfair, as officers had to act when they witnessed crimes. He complained the media rarely showed the damage done by protesters, focusing instead on police carrying out enforcement action.

“The protesters are pathetic and hurt others using their own hands,” he said. “Can broken rubbish bins or shattered glass deliver your demands? Can you get what you want by hurting an officer? You can’t. You are making it even more impossible.”

* Name changed to protect the officer’s identity.