Can Hong Kong break its prison shackles to cut crime?

Advocates of penal reform say the city must drop its punitive approach and take note of measures introduced overseas to stop inmates reoffending

In the United Kingdom’s newest and largest prison, inmates use laptops and do their own weekly shopping. In Norway, prisoners can ski, cook, tend to farm animals and spend time on their own private beach.

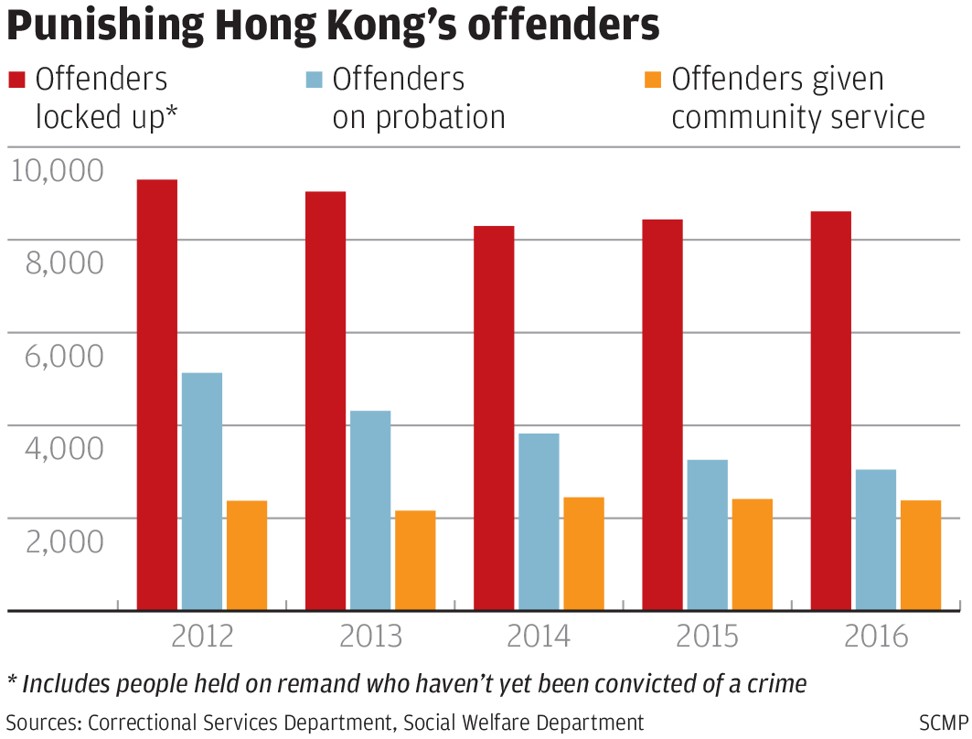

Despite Hong Kong’s less liberal approach to prisons, experts say the city must be doing something right. The reoffending rate has been declining over the past decade, with only 25.9 per cent of inmates released in 2014 reoffending within two years of their release, down from 39.9 per cent of the 2000 cohort.

Even taking into account differing methodology, that’s on the low side. In the United States, 76.6 per cent of inmates released from state prison were rearrested within five years, according to the US government.

Hong Kong’s numbers may be relatively good, but they still mean a quarter of inmates are convicted of a new offence within only two years. With each crime costing the city at least HK$239,000, according to a study, that’s not something to scoff at.

“Certainly, the CSD is trying more efforts to improve our services every day. We are always looking for new methods or new programmes to introduce,” said Senior Superintendent Kelvin Lam Wai-kwong of the rehabilitation branch.

A number of countries have adopted “open prisons”, which give inmates so much freedom that commentators have compared them to communes or university dorms. They follow the United Nation’s “Nelson Mandela rules”, which recommends life behind bars should be as similar as possible to life outside.

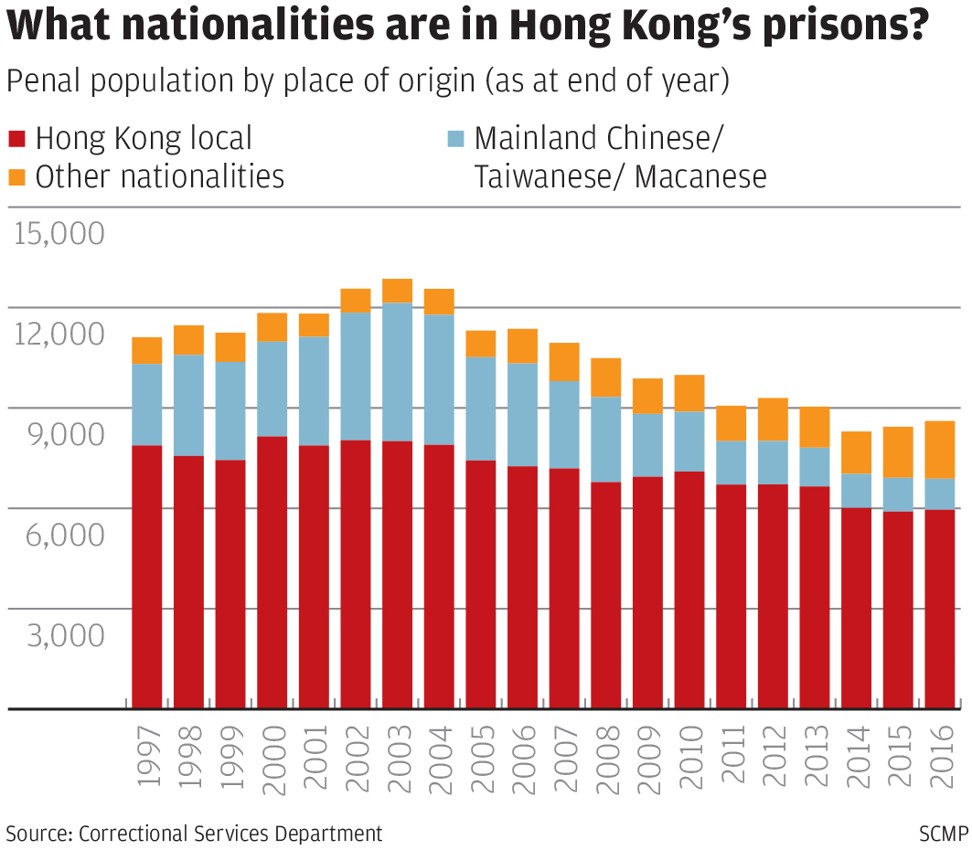

The small Scandinavian nation has been criticised for being too soft, but the statistics seem to speak for themselves: Norway has a low incarceration rate – only 75 people imprisoned per 100,000 compared with Hong Kong’s 115.5 – and when inmates are released, only 20 per cent return.

It’s a similar ethos adopted by UK’s Berwyn prison, where prisoners are allowed laptops and cellphones.

“People are being taken away from their families and their homes – that is the punishment,” the Mirror newspaper quoted governor Russ Trent when the prison opened earlier this year.

In 1982 the CSD launched a “we care” motto, and since then has been working to rehabilitate prisoners – not just punish them.

They are not just bad people – they are normal people, like you and me, who have done something terribly wrong

Despite this, Hong Kong’s prisons are still a lot more punitive than Western countries, says Tobias Brandner, an associate professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Divinity School of Chung Chi College, who researches pastoral care in prisons.

Although open prisons are not being proposed in Hong Kong, Brandner thinks prisons need to focus more on rehabilitation, including giving prisoners more contact with the outside world.

“Families are the most important resources in rehabilitation. What the CSD is doing is just a very small part of what is being done in rehabilitation,” he said.

“At this moment, Hong Kong still doesn’t allow inmates to go out for a few hours, or maybe one day to visit their family,” he said, adding that such a move would help rehabilitation.

Brandner is “appalled” by how little resources are put into education for inmates, most of whom must undertake education in their free time as inmates are forced to work six days a week by law. He wants Hong Kong to introduce peer teaching where educated prisoners could pass on knowledge to fellow inmates, noting: “The more you do for education, the less you do for security.”

Brandner thinks there is an attitude in Hong Kong that prisoners need to be punished and don’t deserve many resources.

“These people in prison, they have their story, and they deserve to be given a chance. They are not just bad people – they are normal people, like you and me, who have done something terribly wrong. But they are more than just their crime.”

Restorative justice, seemingly for all crimes, is used in a number of commonwealth countries, including New Zealand, where government statistics show offenders who have undergone the process have a 15 per cent lower chance of reoffending.

“[It] seeks to repair the harm caused by crime rather than simply punish people,” Cross said. “It has unfortunately been blocked in Hong Kong, through a combination of timidity and short-sightedness.”

In countries like New Zealand and the United Kingdom, there’s only one department in charge of supporting offenders both in and out of custody.

But in Hong Kong, the CSD is only responsible for inmates behind bars. Once they are released they can seek support from the Social Welfare Department or one of over 80 non-governmental organisations.

The current system means a person might receive psychological help while in prison, but there is not necessarily any continuity when they leave, says University of Hong Kong criminologist Kalwan Kwan Ming-tak.

He wants an overall co-ordinating body that will make policies less fragmented.

“I don’t think the general public, the taxpayers, would like to pay more taxes for offender management. We need to have a more centralised public body to coordinate all the resources otherwise the general public will say you could end up spending more money.”

He says there is not enough information sharing between the CSD and groups handling former inmates on the outside, meaning vulnerable offenders slip through the cracks.

About two-thirds of the society’s clients have a history of substance abuse, and they are more likely to reoffend, says Ng, who has master’s degrees in criminology and social work.

“They can get into trouble very easily after they get discharged,” he said. “If we want an even lower reoffending rate, we have to put more effort in helping these people get rid of their drug-taking habits. In Hong Kong, drug addiction and crime are twin brothers.”

“If most people still have a lot of stigma about prisoners, they may not be able to get a job, they may not be able to reintegrate into society because some of their peers will say ‘you are criminals’,” he said.

In 2015, 47 per cent of the former inmates were employed, but only 20 per cent were working full-time, according to a Society of Rehabilitation and Crime Prevention survey.

The Chinese Manufacturers’ Association of Hong Kong is among community groups working to change that. It has run three job fairs since 2014 to help rehabilitated offenders find employment.

“Released offenders face a variety of challenges which may increase the rates of reoffending,” association president Eddy Li Sau-hung said.

We still need to strike a balance between discipline, punishment, filial piety, autonomy, freedom ... not just only looking for individualism

“Giving job opportunities to rehabilitated offenders is one of the measures to facilitate the social integration of them and hence, to prevent crime,” he said, adding that it also benefited business sectors with a manpower shortage.

Despite that, criminal justice analyst Cross says former inmates are still being discriminated against by employers, “which is disheartening for them and wasteful for society”.

“More community education will undoubtedly also help people to understand that a former offender who has been through the penal system must be given a new chance, and not forever viewed with suspicion as someone who might fall from grace again at any time.

“The government should do more to counter mindless discrimination, perhaps by setting an example, and seeking itself to offer more employment to suitably qualified ex-detainees.”

As the UK’s National Audit Office noted in 2012, “international comparisons seldom provide answers of the ‘silver bullet’ variety”.

Both Kwan and Ng caution against following overseas policies to the letter, saying Hong Kong needs to find its own balance of practices.

Kwan compares the city’s corrections policy to the Hong Kong-patented Yuenyeung drink, which combines Chinese black tea with Western coffee.

“We need to build our own unique system to blend with Chinese culture. In terms of Chinese culture, we still need to strike a balance between discipline, punishment, filial piety, autonomy, freedom, so we need to have a different mixture of all these ideas, not just only looking for individualism, for freedom,” he said.

“This is the Hong Kong style: a blend of discipline and rehabilitation.”