A turbulent tenure: HKU vice chancellor reflects on his time at the helm of Hong Kong’s oldest university

Outgoing HKU chief shares his thoughts on the Occupy protests, governing council conflicts, and politics at the heart of education

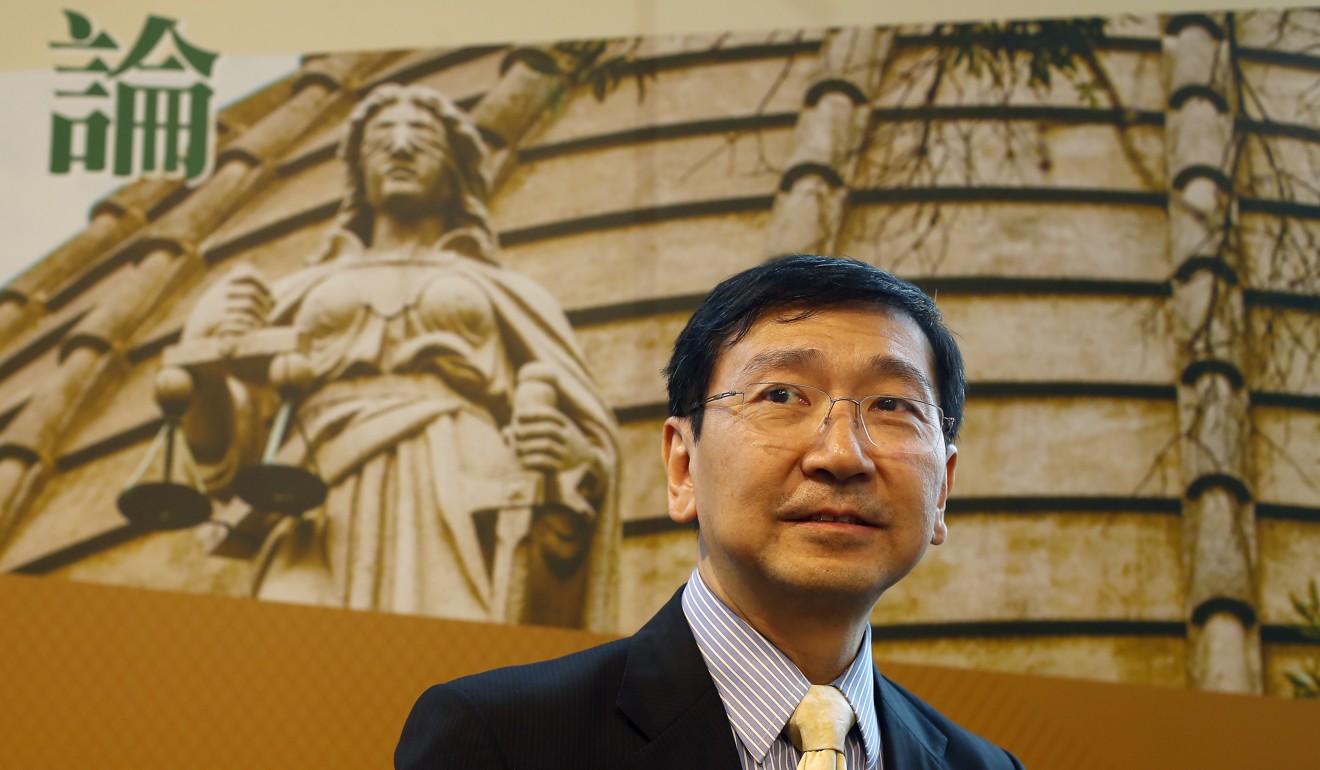

In his simple, uninviting office overlooking Sai Ying Pun’s old buildings and Victoria Harbour, Peter Mathieson turned his back on the sweeping panoramic view, insisting on a particular sofa seat that faced inward.

“I always sit here. I feel comfortable only by sitting here,” the outgoing University of Hong Kong’s vice chancellor said, unmoved by a photographer’s seating advice.

More discomfiting for Mathieson, due to step down this month, were the challenges he faced when dealing with student leaders, colleagues on HKU’s governing council, government officials and even fellow university vice chancellors.

Outgoing HKU chief says Beijing officials have met him ‘several times’ and wishes higher education ‘wasn’t so politicised’

His legs resting casually on a coffee table, eyes away from the bright afternoon sun, the 58-year-old cast his mind back to the “dark moments” so remarkable and arguably inevitable in his stint of three years and 10 months in a post never meant to be free from the politics coursing through Hong Kong.

“Anyone who pretends that their job is always easy, or there are no disappointing moments, I think, would be kidding themselves,” he told the South China Morning Post.

“Yes, there have been some difficult times, and there have been some dark moments.”

At the heart of some of his most wearying headaches: the governing council, whose members are predominantly named by the government. If the members selected had had a less strong political stance, as was the case in the early years after Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, things could have been easier.

But not long after Mathieson took office, the council came under the leadership of Professor Arthur Li Kwok-cheung, a pro-establishment politician whose words are often divisive. (As Mathieson revealed, Li’s failure to engage him on whether to renew his contract prompted him to take up the offer to become University of Edinburgh’s vice chancellor, while he also considered the recent birth of his grandchild in London and his mother’s ailing health before she died.)

I felt there were some people here who prejudged me without knowing anything about me. And I don’t want them to do that to my successor

“As you know I haven’t always got my way in the council. That has led to some difficult situations,” Mathieson said. “I’m only one member of the council so I have one vote in the council, so I can’t dominate the council’s decisions.”

But Mathieson showed no regret in backing Chan.

“Before I even started my job here, Johannes was portrayed to me as somebody that I should be thinking about promoting to a senior post. People who later didn’t support him were actively telling me in the early stages that this was somebody I should take notice of and I should meet with.”

Next head of HKU, Zhang Xiang, must lay down a strict code of conduct for students and staff

The ensuing council meetings degenerated into an unauthorised recording and leaking of supposedly confidential minutes, culminating in students storming into the venue and blocking the way out for the members.

Controversially, Mathieson agreed to call police for help, a decision that alienated his earlier sympathisers. Billy Fung Jing-en, the outspoken student union leader at the time, was arrested and brought to court to face charges of disorderly conduct in a public place, criminal damage and attempted forcible entry. He has since been spared a jail term, instead receiving community service.

In retrospect, though, Mathieson was content with the way the protests were dealt with, adding he would not have handled the incident differently.

Outgoing HKU head calls visit to Occupy protesters the ‘defining moment’ of his term

In a society treading a fine line between academic freedom and political correctness, trial and error seem job requirements for anyone leading a reputable university in the city.

Mathieson’s stint coincided with a period when Hongkongers voiced unprecedented disapproval over the chief executive’s power to appoint council members.

A three-member expert panel was subsequently set up by the council to review the university’s governance structure in 2016, but the suggestion from two of the experts to strip the chief executive’s power was snubbed. The council later endorsed another proposal from a working group made up of council members to have committees advise the chief executive on such matters, reserving the final say for the city’s top official.

But the wording in the final text went against his wishes.

Colonial privilege, academic freedom and chicken feet: reflections of a British veteran HKU professor

“In my mind we were not condemning discussion of Hong Kong independence,” Mathieson said. “Unfortunately, the way the statement came out, those two things got juxtaposed, and people linked them. But in my head, they were two separate issues.”

When asked why “hate speech” was not categorically condemned in the statement, Mathieson said he had put that phrase in the original draft, before it was crossed out after further negotiations.

“If I’d had my own way, I probably would have issued a slightly longer and a slightly more detailed statement which would have explained the position more clearly, and that might have prevented some of the ambiguity.”

The compromise was made in the interest of the university, Mathieson said, adding: “I felt there was a case for us to make a statement for HKU to be part of the joint statement.”

The setbacks he faced in and out of the university would have been unexpected in October 2014, when Mathieson, barely six months after leaving the University of Bristol as medical dean, was hailed as a hero. During the Occupy protests, he walked into a crowd of tens of thousands of protesters, urging for calm and patience amid rumours of police escalating their use of force.

I never said Hong Kong independence talks abused free speech: HKU chief Peter Mathieson

“Various people said [Chinese University vice chancellor Joseph Sung Jao-yiu and I] may have helped by going there – we may have helped prevent escalation,” Mathieson said. “If that was the case I’d be very happy about that.”

He added he was satisfied that the university came through that period with its principles intact, even though there was “no rule book to consult as to what to do or what to say”.

In his parting message to students and staff, Mathieson planned to hail HKU’s rising global rankings in recent years. He also called it a “very lasting contribution” for new deans to be chosen for seven of the university’s 10 faculties during his tenure, taking pride in the “quality of people we have managed to recruit”.

If anything, his message was a veiled rebuttal to all the humiliating remarks he suffered before starting his HKU position, when veteran professors openly doubted his fitness for the job. He hoped his successor – Professor Zhang Xiang, a mainland-born mechanical engineer at the University of California, Berkeley – would be treated fairly.

“Please just give him a chance,” he said. “I was in that same situation – all I wanted was to be given a chance.

“I felt there were some people here who prejudged me without knowing anything about me. And I don’t want them to do that to my successor.”

Already, Zhang has raised eyebrows with his call to obtain funding from mainland authorities, leaving staff and students in doubt about his ability to defend institutional autonomy. Mathieson said it was not unusual for HKU to receive funding from the mainland government.

Top pick for new HKU vice chancellor faces questions over research links to US military

“I think all universities in Hong Kong are very interested. As you know, most access to mainland research funding has to be done in collaboration with a mainland university or other mainland entity. We have explored how we can benefit from that in the same way as everybody else.”

As political observers noted, the city is set to be subject to even stronger attention or even policy direction from Beijing in the coming few years. How far academic integrity can be preserved is a matter of concern for those in and out of the campuses.

In offering advice to Zhang, Mathieson said: “Decide what you believe in, decide what you want to achieve with the university, and make use of all the fantastic resources that you’ve got, particularly in terms of people and facilities and funding. I said to him, if you want to be a university president, this is a great place to do it.”

For Mathieson, however, his efforts had not proved a source of considerable joy. Asked to name a bright spot during his tenure, he could not identify one.

“I think all of my bright spots for my whole life, and especially for the last four years, were personal and connected with my family,” he said. “To be honest I have had very little relaxation time in Hong Kong. I feel like I’ve worked very hard whilst I was here. It’s a busy job – it’s a seven-day-a-week job – and I’ve always worked hard and I’ve given it every ounce of my energy. And I’ve always tried to do the best.”