Warm welcome for likes of cultural giant Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’ unlikely in today’s Hong Kong, observers fear

- During the 1950s and 60s, ‘coming from the mainland’ did not have any derogatory connotations, historian says

Martial arts novelist Louis Cha Leung-yung’s death on Tuesday has meant the loss of another cultural giant who had settled in Hong Kong during the peak of political turbulence in mainland China and came to be fully embraced by the city.

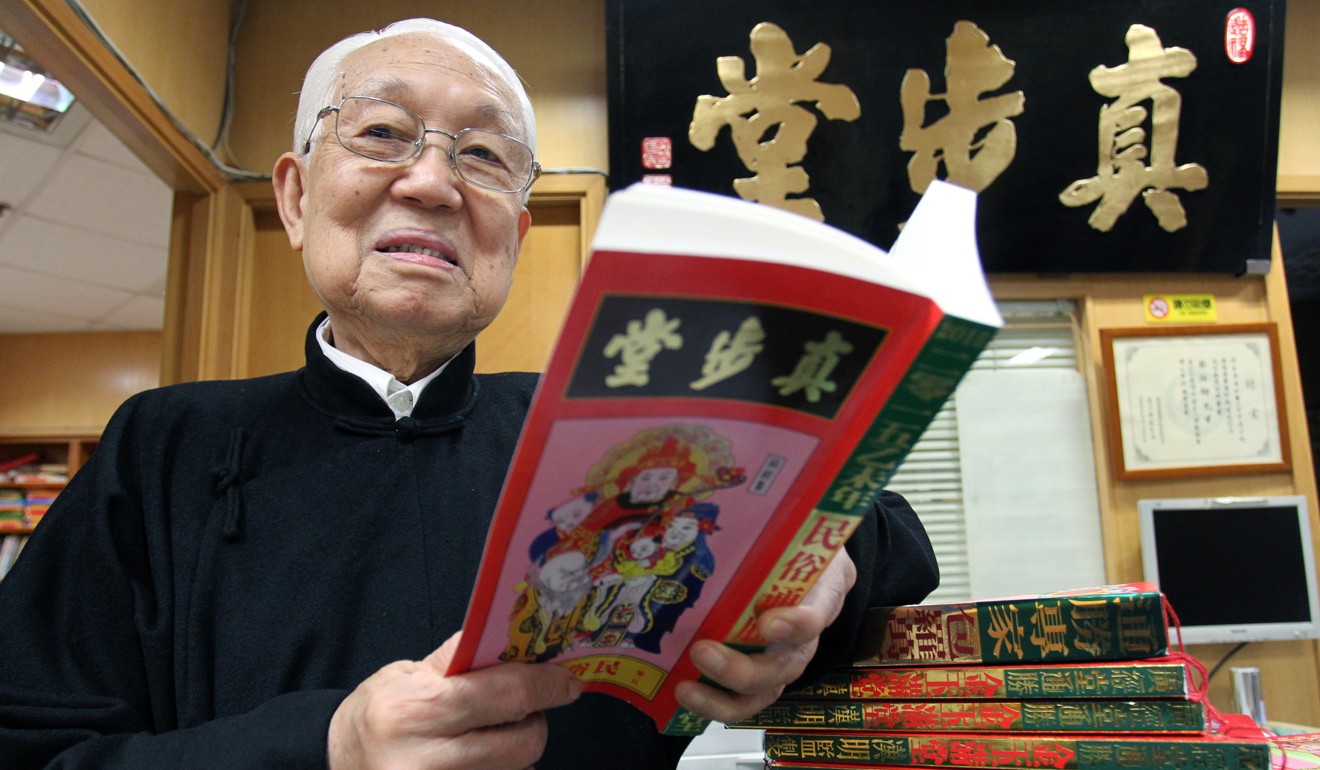

Because of the divisive political atmosphere in today’s Hong Kong, observers said, if Cha, distinguished sinologist Professor Jao Tsung-i and feng shui master Choi Park-lai – who both died this year – had settled in the city in recent years, they could have found themselves falling victim to the hostility displayed towards mainlanders by some sections of society.

During the 1950s and 60s, “coming from the mainland” did not have any derogatory connotations, historian Professor Lau Chi-pang said.

“Instead, it was appreciative. We called those businessmen fleeing from the mainland entrepreneurs coming south. We had intellectuals coming south. And we had workers coming south. They all were welcomed as a contributing force to the growth of the city,” said Lau, a specialist in the history of Hong Kong and modern China.

Fans flock to Jin Yong Gallery to mourn literary giant Louis Cha

Those days are gone. In recent years, instead, there had been “anti-locusts” campaigns in Hong Kong. The term “locusts” was commonly used by some localist activists to refer to mainlanders, who, they claimed, had come to Hong Kong to “eat up” the city’s resources.

Cha, 94, was a respected journalist, community leader, and, above all, a celebrated author who used the pen name Jin Yong.

Chow Po-chung, associate professor at Chinese University’s department of government and public administration, said, citing Cha’s newspaper Ming Pao as an example, media in the 1960s could usually operate at arm’s length from government influence.

Wuxia legend Louis Cha battled liver cancer and dementia in twilight years

“So long as you were not going too far, the colonial government would not bother much about whether you were critical of the Communist Party or the Nationalist Party,” Chow said.

“This is, through an accident of history and circumstance, what helped give such an advantage that was unique to Hong Kong. I am afraid we can hardly have another Louis Cha legend now.”