Hong Kong literary giant Louis Cha ‘Jin Yong’ was ever ready to voice unpopular opinions

- Novelist also enjoyed a parallel career as a journalist and commentator

- He fell in and out of favour with Beijing repeatedly over the decades

Louis Cha Leung-yung may have been best known as a prolific writer of martial arts novels, but he was also a colourful, influential figure in journalism and politics.

He had his own newspaper, which he used unabashedly to promote his controversial political opinions, disregarded his critics, and fell in and out of favour with Beijing at different periods over more than three decades.

Cha, who died on Tuesday at age 94, started out as a journalist and translator for the Ta Kung Pao newspaper in Shanghai in 1947, and moved to its Hong Kong office the following year.

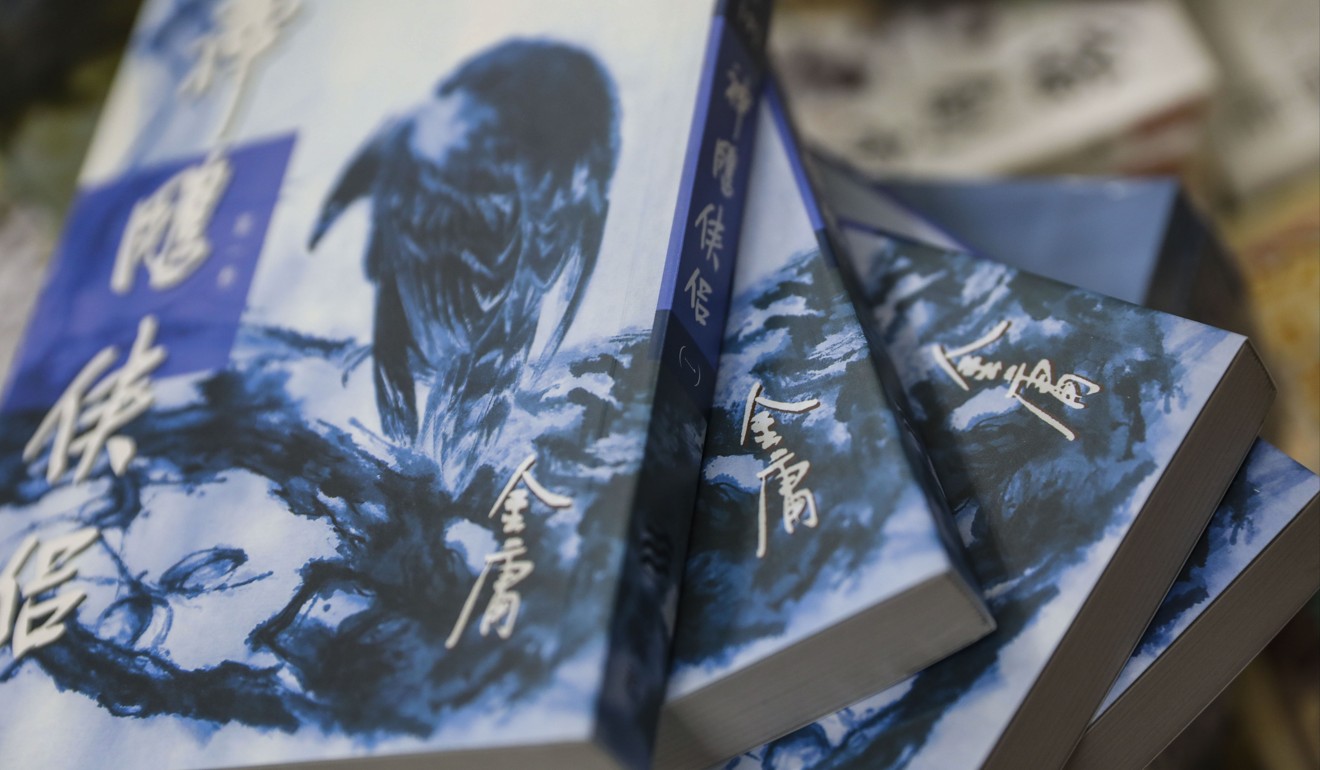

In 1959, four years after his first novel, The Book and the Sword, was published and became an instant success, he co-founded Ming Pao Daily News.

Cha wrote under the pen name Jin Yong, and at first he wanted the Chinese-language daily to run his own work, as a way to beat those who were making pirated copies of his novels.

Ming Pao serialised his hugely popular novels, and in the early years also made its mark with horse-racing tips and photographs of swimsuit-clad models.

Within a matter of just a few years, however, the paper changed direction and adopted a strongly anti-communist position, in the wake of a devastating famine blamed on the failure of Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward economic and agricultural programme.

In 1962, Ming Pao impressed readers with a series of detailed reports about the influx of mainland refugees into Hong Kong, triggered by the famine and widespread social unrest in China.

In his editorials over the years that followed, Cha condemned Beijing for testing the atomic bomb while its people suffered in poverty, and criticised the Cultural Revolution, saying it threatened to destroy Chinese culture and tradition.

His views drew harsh criticism from Hong Kong’s left wing.

When the Cultural Revolution spilled over to Hong Kong in 1967, triggering riots in the British colony, Cha’s firm position against the left wing was believed to have made him a target for assassination.

It was not until the 1980s, with Deng Xiaoping in charge and introducing major reforms in China, that Ming Pao began to soften its attitude to Beijing.

Wuxia legend Louis Cha battled liver cancer and dementia in twilight years

Cha met Deng in Beijing in 1981 and was appointed as a member of the Basic Law Drafting Committee and Consultative Committee in 1985 looking into drawing up a mini-constitution for Hong Kong after it was handed back to China by Britain.

In 1988, Cha found himself in the thick of controversy after he co-presented a conservative proposal for the city’s post-1997 political reforms.

The proposal, which was adopted partially by Beijing eventually, suggested that Hong Kong elect its first three chief executives by a “broadly representative” Election Committee, before holding a referendum in 2011 to decide whether the chief executive should be elected by universal suffrage.

He cared about the well-being of the country and the people regardless of the regimes in power

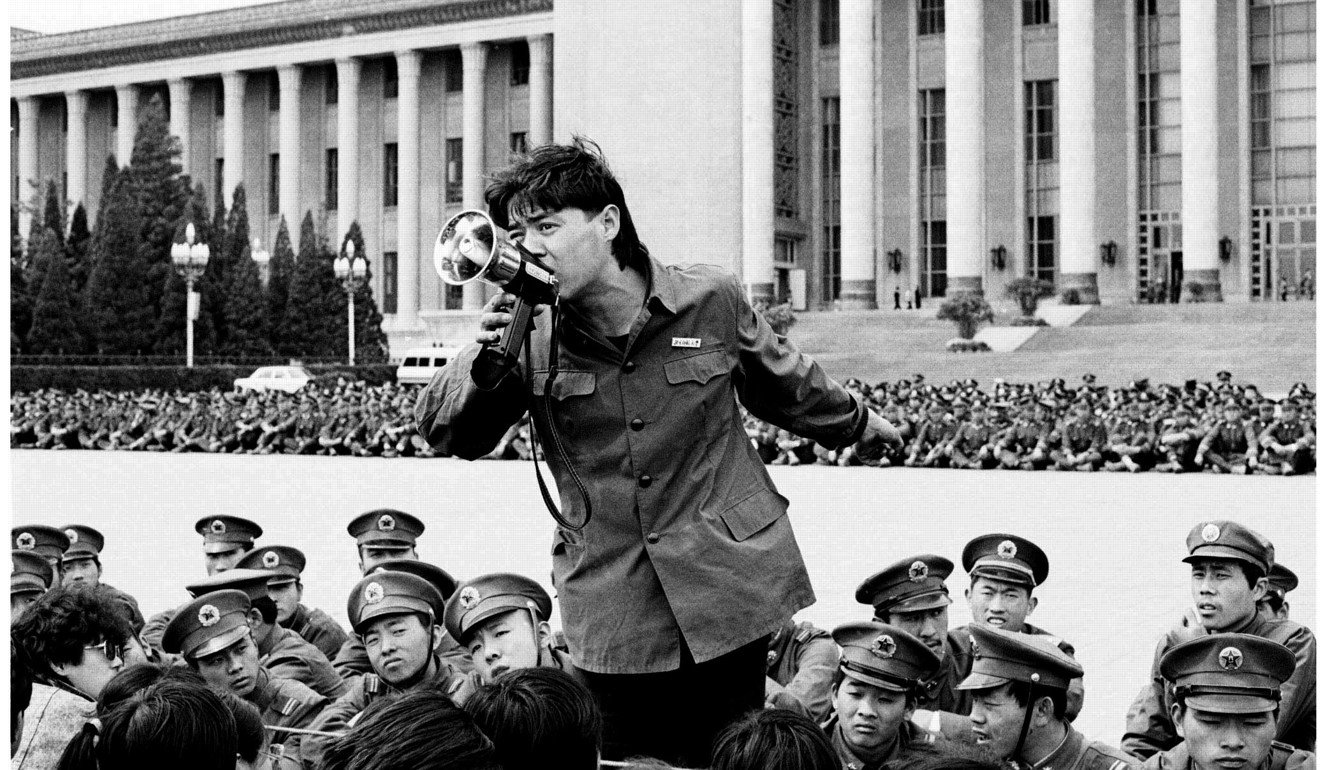

The model was denounced by liberals and Cha became a target of attack. Protesting college students burned copies of Ming Pao outside its offices in Quarry Bay.

Ming Pao ran three editorials over three days in a row from November 25, 1988, arguing that universal suffrage did not necessarily mean direct election, citing the election of United States presidents by the electoral college as an example.

Academics and journalists blasted Cha for using Ming Pao to promote his political position, but Cha stood his ground, declaring that he had the power to decide what to do with his newspaper.

Some senior editors of Ming Pao, including deputy chief editor Cheung Kin-bor and managing editor Simon Fung Shing-cheung, resigned, although both returned later and Cheung went on to become chief editor in 1997.

Tributes pour in for Chinese literary giant Louis Cha

Veteran journalist Cheung Kwai-yeung, author of the book Jin Yong and Ming Pao Daily Legend, said Cha believed media organisations existed to serve their owners, rather than the public interest.

Cha fell out with Beijing again after its bloody crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in 1989, writing more than 30 editorials in support of student protesters.

He resigned from the Basic Law Drafting Committee after Beijing declared martial law on May 20, 1989. And after the tanks rolled in on June 4, Cha was reduced to tears as he condemned the crackdown on protesting students.

Cha stepped down as chairman of Ming Pao Enterprise Corporation in 1993, handing over the reins to the 33-year-old Yu Pun-hoi, whose budding media group CIM Holdings had become Ming Pao’s largest shareholder two years earlier.

Cha’s tie with Beijing improved in 1996 again when he accepted the offer to join the Preparatory Committee overseeing Hong Kong’s handover.

Editorial: Louis Cha, the man who united Chinese in name of chivalry

Tung Chiao, chief editor of Ming Pao Daily News from the late 1980s to mid-1990s, said Cha held different political views at different periods.

“Some were correct while some were wrong,” Tung said. “You can’t blame him. He was a traditional Chinese intellectual who cared about the well-being of the country and the Chinese people regardless of the regimes in power.”

Additional reporting by Joyce Ng