How Hong Kong’s embattled police force is holding the city back from the brink against all odds

- In a series of in-depth articles on the unrest rocking Hong Kong, the Post goes behind the headlines to look at the underlying issues, current state of affairs, and where it is all heading

- Once a demoralised force under constant attack by protesters and widely criticised by the public, police are now finding new strength in their role as the last line of defence to prevent total chaos in the absence of a political solution

“Your words have completely written off our efforts in maintaining law and order over the past few months, and written off our sacrifices, too. You have completely disappointed us.”

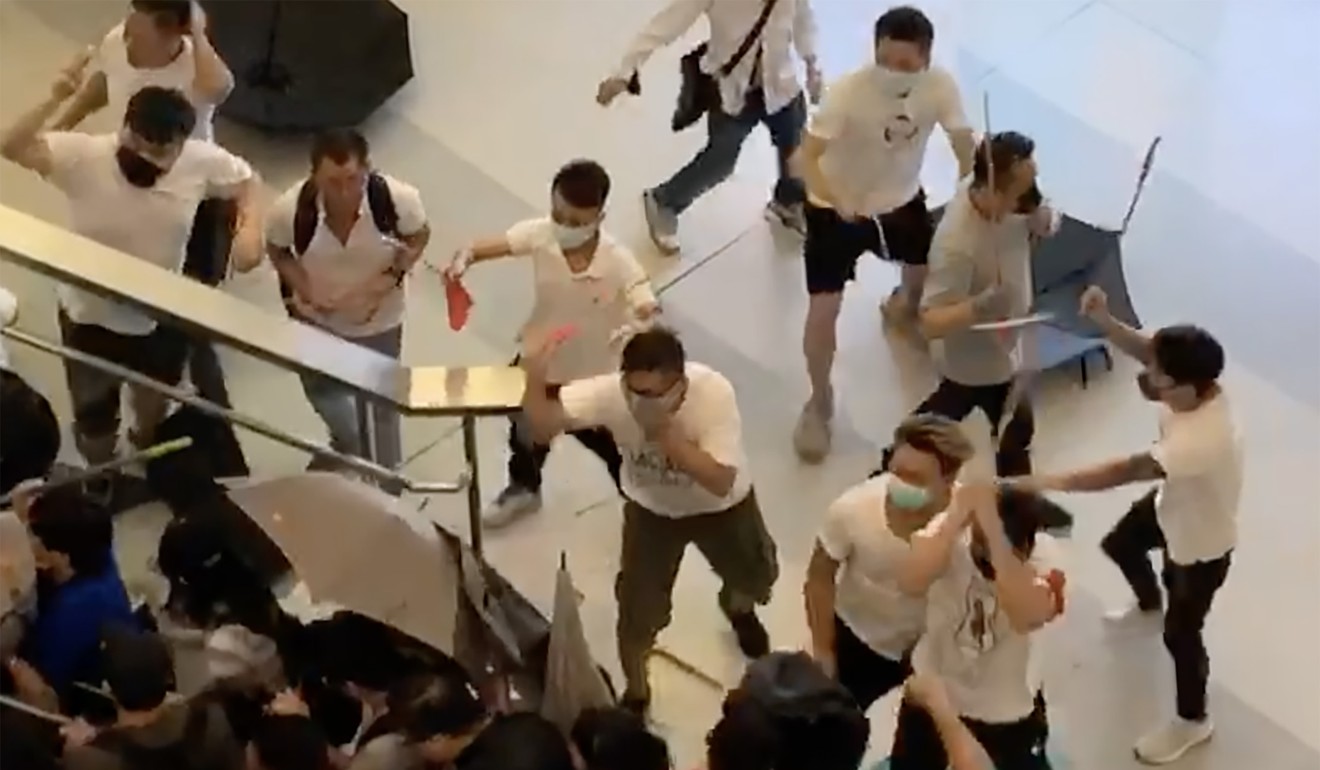

They also assaulted bystanders and journalists at the scene with sticks, at one point storming a stationary train full of terrified passengers in unprecedented scenes of violence and anarchy. By the time police arrived in force, the attackers had fled.

While tear gas was being fired to disperse crowds in Sheung Wan, police in Yuen Long were tied up with a series of emergencies including other fights, assaults and a fire, the force said.

The lawlessness at the railway station that night left at least 45 people injured and marked a watershed in the breakdown of already fraught police-community relations.

Protesters as well as the wider community seized upon the presence of suspected triad gangsters among the white-shirted mob and accused police of colluding with organised crime.

Chanting “hak se wui” – the Cantonese term for gangsters – at police became the insult of choice, replacing the previously popular preference for calling them “dogs”.

While police sources admitted serious errors of judgment behind the failure to respond in time, the force was united in refusing to apologise for it, given what frontline officers had been through over the previous weeks.

Many officers felt they were unfairly being made to bear the brunt of public anger and protest violence over a political problem that the government should have been solving.

It was a police force feeling betrayed and abandoned but which nevertheless faced waves of attacks by protesters the very next day, using tear gas, rubber bullets and sponge grenades to clear the streets.

Relations between the ICAC and police had long been testy – the watchdog was set up in 1974 to stamp out rampant corruption in the force and other government departments – with professional rivalry playing a part, and some senior officers privately characterised it as the ICAC jumping on the anti-police bandwagon to take the moral high ground and settle old scores.

Under attack from all sides

One of the biggest concerns raised by top police commanders and operational chiefs working both in the field and at headquarters, speaking to the Post on condition of anonymity, was what they described as the growing acceptance of violence against officers.

The actual physical violence against police officers is escalating, but no one is concerned about it

An officer suffered second-degree burns when he was hit by a petrol bomb thrown into the Tsim Sha Tsui police station compound which came under arson attack by protesters who besieged it for hours on August 11.

One of them, a young woman, was hit in the eye and blinded by a beanbag round, according to protesters who have turned her image into a symbol of resistance and testimony to police brutality.

“I do not know whether it was a beanbag round, or a metal ball [fired by protesters],” assistant commissioner Terence Mak Chin-ho said at a police briefing, suggesting that a protester’s catapult might just as well have been to blame.

But for police, the case is another example of the dice being loaded against them, and how injuries among their ranks are ignored in the louder narrative about protesters being brutalised.

“The actual physical violence against police officers is escalating, but no one is concerned about it. If you go through [the popular messaging app] Telegram, there are all sorts of plots, every single day, saying how to kidnap police officers, how to kill police officers, and things like that,” a top operational officer said.

“The general sentiment in society is that this kind of thing is acceptable. As long as members of the public in general are not involved, are not obstructed, they are fine with it. As long as they are not the victims.”

In addition to the physical violence, and the daily pressure of having to face hostile crowds for hours on end, officers have also been put under immense mental and emotional stress because of a relentless campaign of online abuse, harassment and provocation against them.

Expatriate officers in particular have been singled out because of their visibility as frontline commanders and “foreigners” ordering the use of force against locals.

I think it is a very orchestrated, smart campaign targeting individual commanders

“The campaign against me is very organised and sophisticated. They have taken it to my home country, where I was born, they got my parents’ full names, pictures of my children,” one of the officers in question told the Post.

“I think it is a very orchestrated, smart campaign targeting individual commanders – let’s get him withdrawn, then the next one, let’s get him withdrawn, and so on.”

The operational chief who spoke to the Post said “everybody was crying” when police held “internal sharing sessions” for staff to talk about what officers’ families were going through.

“For example, in school, children are being picked out in front of the whole class. Drawing a dog on the blackboard, and asking the whole class, ‘what is it?’ It’s a dog, son of a dog, things like that,” he said. “But when we receive such complaints, the parents do not want to mention the school name because their children have to continue studying there.”

How much force is excessive?

“Officials can be seen firing tear gas canisters into crowded, enclosed areas and directly at individual protesters on multiple occasions, creating a considerable risk of death or serious injury,” she complained in a statement.

One seasoned commander explained the extent of the restraint police were displaying in this crisis by drawing a comparison with the case of a homeless Nepali man who was shot dead by an officer in Ho Man Tin in 2009.

The man had been living rough on a hillside and allegedly used a wooden stool to attack the officer responding to a complaint about him. He was shot in the head.

“That shooting was justified because the officer on the scene felt his life was being threatened. Just think about it – the threshold back then for the officer to draw his weapon and open fire,” the commander said.

“Now look at how our officers are being attacked in this present situation. You’ve seen individual officers separated from the others, being savagely assaulted and beaten. Their lives are obviously in danger and yet they don’t pull out their revolvers and use lethal force, even though they have a right to. What does that say about the threshold now, what does that say about restraint? What more proof do you want of how much we’re holding back?”

How Hong Kong leaders spurned chance to listen to public opinion

Assistant commissioner Mak said the officer had made “absolutely the right decision” as his life was “in great danger”.

More than two months into the protest crisis, police refuse to admit they are getting more aggressive in their anti-riot tactics, touting the bureaucratic line that they are merely responding with a level of force that matches the intensity of the attacks against them.

But both reports on the ground and video footage of police in action, especially during late-night operations when they swing into action to clear the streets, clearly show they are not holding back as much as they used to.

China’s armed police drill near Hong Kong as protests enter 11th week

The Special Tactical Squad of elite anti-riot personnel known as “raptors” can be regularly seen swinging batons and slamming protesters to the ground to subdue them, kid gloves no longer on.

“If there are no attacks on the police, if there is no use of violence, of course there is no need for the police to resort to the use of force,” was how Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu defended it.

Turning of the tide

Why Hong Kong protesters view police as the enemy

In the days and weeks that followed, Beijing’s condemnation of the protesters was frequently tinctured with praise for the city’s embattled police force.

Mainland Chinese officials began holding up Hong Kong police as the real heroes, the last line of defence stopping the city from plunging into anarchy.

While images of the officer went viral, with protesters and the Western media portraying him as an out-of-control policeman threatening to use lethal force, mainland Chinese newspapers hailed him as a hero who “moved all of China” by not pulling the trigger, even when his own life was at risk.

“It’s the responsibility of the police to guard homes and protect loved ones. Hong Kong police, you are guarding peace in society on the front line; 1.4 billion Chinese are standing behind you, guarding you … we support you!” a host declared on CCTV, the state broadcaster.

Another episode of appreciation saw the visiting Hong Kong police soccer team getting the biggest and longest applause recently at the opening ceremony of the World Police and Fire Games in Chengdu.

Zhang Xiaoming, head of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office was quoted as saying: “Police have sweated and bled, we cannot let them cry.”

Multiple sources from Beijing and the Hong Kong government admitted that, to a certain extent, the police force as a whole was even more important than the chief executive in the eyes of China’s leaders.

Two months on, what do Hong Kong protesters really want?

The appointment of Lau, a respected veteran and tough operator who handled the Occupy protests of 2014 as well as the Mong Kok riot of 2016, was welcomed by many in the force.

“He is the best-qualified person to guide the force through the present challenge and set us on the right course for our future,” one high-ranking officer said.

The unprecedented use of force at Kwai Fong station marked a clear change in tactics – in the past, police would allow protesters who attacked them to retreat into the MTR system to surface at a different location for another guerilla-style assault.

They also took it to a new level the same day at Tai Koo station, chasing after protesters and piling onto them at the top of a long, steep escalator, where they beat them with batons and fired pepper pellets at close quarters.

No longer down and far from out

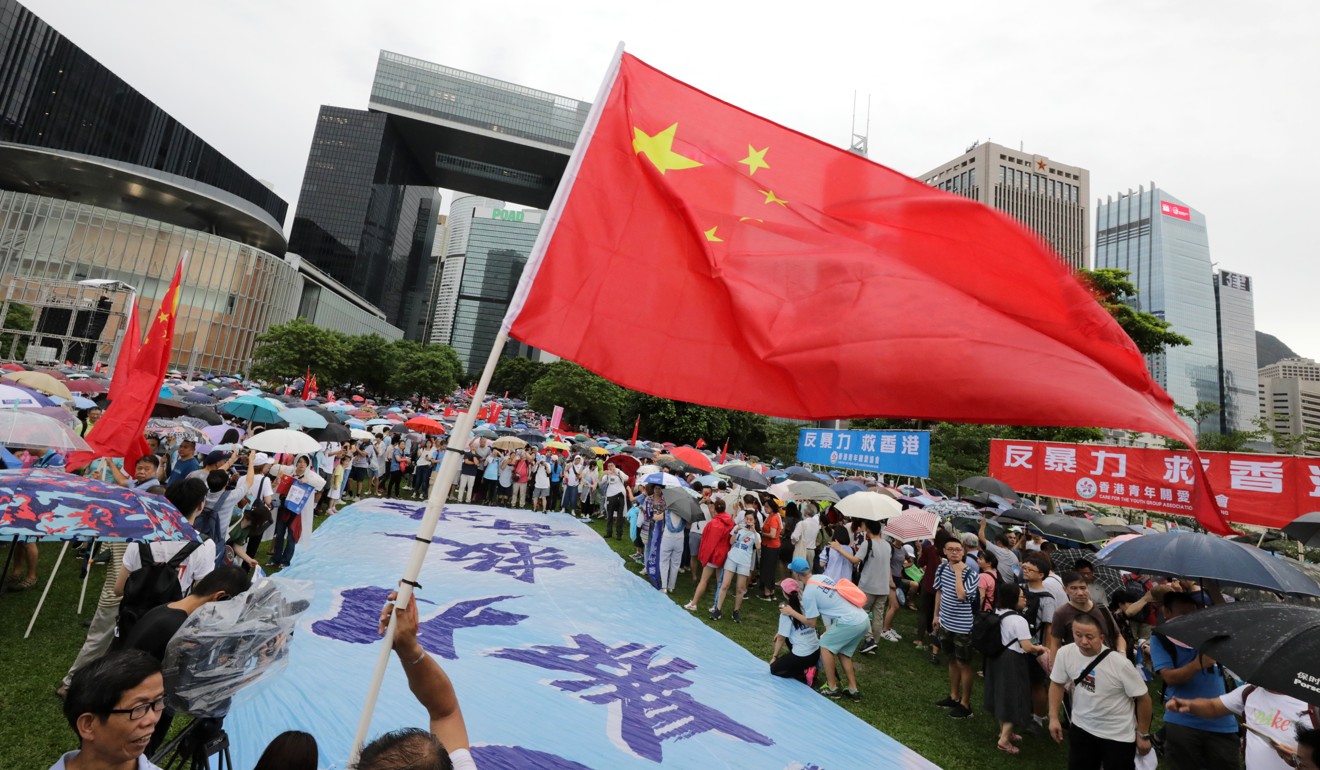

In recent weeks, Beijing and the local government have been mobilising their forces and loyalists, as well as citizens distressed by the violence and breakdown of law and order around them, to counter the protest movement with their own rallies and publicity events.

This has manifested in mass gatherings in support of the police force and morale-boosting visits to police stations by citizens expressing their appreciation for the sacrifices made by frontline officers.

Hong Kong’s tycoons have also started speaking out against the protest violence, with some turning up at one of the latest pro-police rallies.

Correspondingly, with the violent groups among the protesters appearing smaller these days, and a distinct change in their tactics – after blocking roads and confronting police lines, they have been retreating at the last moment instead of meeting them head-on – police are resorting to quicker action.

The strategy now is to charge and subdue the radical elements among the crowds at an earlier stage instead of allowing hours of build-up and belligerence before taking action at the very end.

They have also been rejecting more applications for protests to reduce the risk of violence.

Police are not only getting more aggressive on the ground, they are also talking tougher and with more confidence, sending out the message that morale remains high and they have the stamina, commitment and resources to handle whatever the protesters throw at them.

A retired veteran of the force, with extensive experience as a senior commander during British colonial rule, told the Post that the city had yet to see the full capability of Hong Kong police.

“In every engagement when they are allowed to use their measured tactics, they prevail over the rioters. The problem is flip-flopping leadership from the police head,” the retired veteran said.

“There is a playbook for escalating the posture of the force – it’s the well-resourced and tested Force mobilisation plan [Formob].

“Virtually the whole organisation goes on an anti-riot footing. The auxiliary duties get activated with all officers working 12-hour shifts. Regular policing is limited to emergencies and major crimes.

“Formob can be incremental, in phases or across the whole organisation; curfew zones could be imposed across certain areas and at certain times; you’d likely see mass arrests of ringleaders and suspects with the judiciary asked to expedite case hearings.”

Hong Kong has not reached that stage yet, but it is a very different police force facing the protesters from the days of the letter the inspectors wrote to the government – more confident, aggressive and convinced that they are indeed the last line of defence holding the city back from the abyss.

At the same time, police are also asking how much longer they are expected to carry on playing this role when the real end to the crisis can only come through a political solution.